The Righteous, Musical Violence of Ape Out

Stephen Mansfield improvises a free jazz solo.

Ape Out has to be one of the most violent games I’ve ever played. It might not have the gory dissections of something like Mortal Kombat, but what it lacks in detail it makes up for in abruptness, consistency, and straight-up volume. Videogame violence has never been this loud. And this is a different kind of loud than what we’re used to seeing from videogames. This isn’t a cry for attention or some faux-edginess that’s trying to make your parents mad. Ape Out is a primal release of righteous anger. It doesn’t present violence as a fun waste of time or a taboo to be broken, but instead as an oppressed creature’s tool for justice.

The closest comparison for Ape Out may be Hotline Miami: a game with similar mechanics, a strong aesthetic hook of its own, and that same taste for blood. But Hotline Miami’s violence is a lot more pensive, asking the player to stop and think about what they’re doing at every moment. It’s a game with a deliberate pace, disturbing imagery, and a narrative about meaningless violence that turns into a sort of critique of the player: a metatextual narrative that asks us why we like playing violent games so much. By taking this basic formula and turning it on its head, Ape Out makes the counter-argument to Hotline Miami’s assumptions about how and why violence occurs. Ape Out argues in favor of violence.

Ape Out’s distinct musical direction differentiates it from Hotline Miami and defines our experience of its violence. When I say that Ape Out’s violence is loud, I mean that literally. The violence in Ape Out is set to a jazz drum solo, every moment of the action corresponding to a snare or a kick or a rimshot. Enemy guns are loaded and fired with what become identifiable rhythms. Cymbals crash as you splatter enemies against walls. Percussive elements such as alarms, explosions, and the shattering of glass join the chorus of drums. And these bursts of sound are backed by the controlled pitter-patter of the ape’s footsteps that maintains the pace of the action. The game sounds like it is being scored live by a real drummer sitting in the room with you and reacting to your play. There is no string section and no melody, only the most violent of instruments being played violently.

Contrast this with Hotline Miami, a game partially made famous by its collection of synthwave tracks. Every note in Hotline Miami’s score is fine-tuned. The beats play in what quickly become repetitive loops with no room for anything to surprise you. The music acts as a soundtrack to your killing spree, not a reaction to it. The thrumming, driving baselines are meant to lull you into a zone of focus, continuing unbroken even through player deaths. Only at the end of the level, when you are forced to silently walk through the carnage you created, does the music cut off. These are the two extreme modes of Hotline Miami’s music, both pensive in different ways, and neither the impulsive celebration of violence that accompanies Ape Out.

The musical ideas in Ape Out draw on the 1960s free jazz movement. The game does this explicitly, playing “You’ve Got To Have Freedom” by free jazz saxophonist Pharoah Sanders over the end credits. Free jazz was a movement that was less concerned with tonality and coherence, and more interested in a form of abstract musical Expressionism. This led to music that felt lively, chaotic, and also abrasive and exhausting. It’s usually a collection of four or so musicians with something to say, each playing over top of the other one to get their point in. But something incredible comes out of these cacophonous conversations, and it’s a music that feels rawer and more emotional than most other music. It’s not pretty, but it’s not trying to be pretty. Without having to worry about traditionally accepted forms of beauty, the artists are instead more freely able to express themselves and their ideas through their music and create something dissonant but beautiful in its own right. In the broader context of the Civil Rights era, the affordances of free jazz gave black artists an outlet to express anger, desire, violence, despair, and a whole host of other relevant emotions often confined by traditional forms of music and society at large.

Confinement is also at the heart of Ape Out. While not big on traditional storytelling, it is a game about an ape who has been captured, whose ability to express itself has been limited. And then, from the moment you first hit the attack button until the end of a level, music starts and never stops. Unlike Hotline Miami, whose music plays from the moment you arrive at a level, the music in Ape Out does not start until the ape breaks free of its confinement with its initial violent burst. This moment, and everything that follows after it, is both an act of violence and an act of creation. It creates this noisy and energetic soundscape, and also the possibility of freedom for the ape. Ape Out positions violence as not only being creative in addition to destructive, but also as having creative potential through its destruction, for the ape cannot create without destroying the already violent world that confines them.

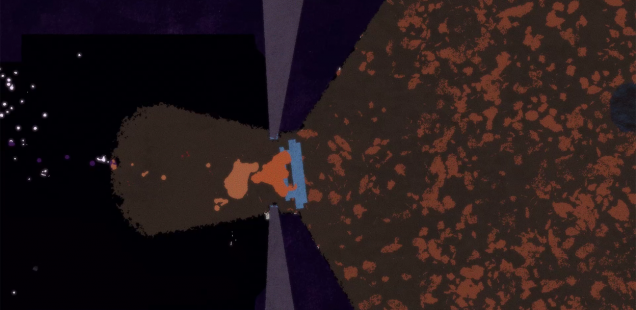

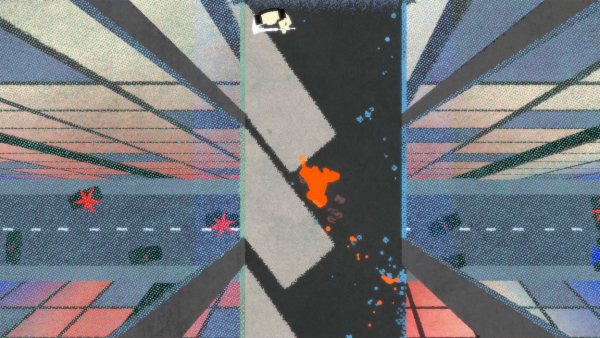

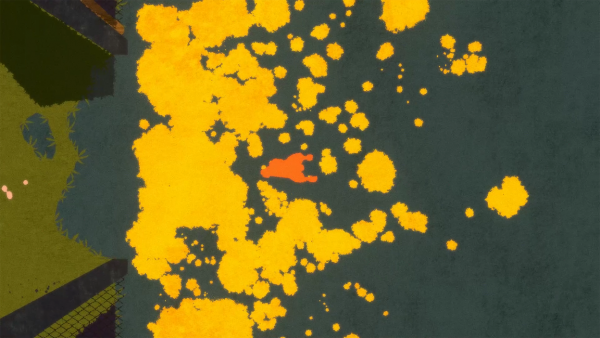

This idea of creative violence expresses itself through more than just the music, too. For one, the enemies in Ape Out are not realistically rendered humans but human-shaped paint buckets that coat the walls and floors that you throw them against bright red or the occasional antiseptic white. The game also requires the player to play creatively. Through a mixture of tight camera angles and randomly generated room layouts and guard placements, you never know what is waiting around the next corner. Guards will appear as a minor surprise, forcing you to think on your feet as the drums propel you forward. You have to play by feel, and your improvised play makes you the composer of the improvised soundtrack.

Hotline Miami, on the other hand, is a game where you can plan out every move. You play as the infiltrator as opposed to the escapee and have a wide range of vision that allows you to think through your plan of attack. And even if things go wrong, the guards walk on the same predictable loops every time, giving you the ability to refine your route further with each attempt. You don’t improvise; you rehearse. There is a theoretical, fully optimized run of Hotline Miami that is as finely tuned as its soundtrack. No such thing could exist for Ape Out, because Ape Out is a game that finds that sort of perfection unsatisfying. It lives for chaos.

But despite all of these ways that Ape Out is more celebratory of violence, it is also less obsessed with it. Earlier I called Hotline Miami’s violence pensive, and part of that pensiveness comes from the fact that it wants you to be thinking about violence at every moment. The infiltration portion of the game wants you to carefully consider how you are going to enact your violence, as one wrong step will result in your own death. The end-of-level walk through the carnage creates a moment without any external pressures that allows you to think about just how many people you have killed. The game opens by asking if you “like hurting other people.”

Inversely, Ape Out doesn’t give you time or reason to think about what you’re doing. There is no suggestion that it could possibly be wrong, and the notion that it’s right does not need to be explicitly stated. It is simply assumed. The ones in Ape Out who “like hurting other people” are the ones who are using the ape for experiments and entertainment and whose first instincts are to unleash an entire arsenal upon a creature that would simply leave them alone if given the chance. The game doesn’t force the ape to kill every enemy, and his main way of doing so is by pushing them away, an act that shows the ape acting reflexively and defensively. The ape is violent and destructive, but the morality of the situation is black-and-white in favor of that destruction.

Back in 2012, Rami Ismail said, “I realize how neutral Hotline Miami is in its application of violence: it does not glorify it, nor vilify it. It shows how ugly violence is and does not attach any value to it. It is what it is.” Ape Out takes the opposite approach. Ape Out does glorify violence. It glorifies its violence as the justice of an oppressed being and a beautiful act of creation. But it also doesn’t only glorify violence. At the end of the game, when the ape is finally free, “You’ve Got To Have Freedom” kicks in with a full quartet playing, and the ape’s true power to create has been unleashed. The drums were a beautiful tool, but they were also the only tool available. With its newfound freedom, the ape can now sing.

Stephen Mansfield is a freelance critic based out of New Jersey who just finished his undergrad English studies and can’t stop thinking in metaphors. You can read more of his stuff at stephenamansfield.com and follow him on twitter @mmmfield.