Killing Ain’t So Bad

Ethan Woods considers the pitfalls of a protagonist who learns through narrative.

Education, education, education. Brother, we don’t need no stinking education.

The opening to this year’s Tomb Raider saw Lara Croft wrestle with the type of hurried, violent insanity that had yet to be witnessed outside of a late-night episode of Hollyoaks. Stranded, kidnapped and impaled, you’d have thought the first thirty minutes of her field trip would have put her off adventuring for a lifetime. In a talk with IGN however, lead writer Rhianna Pratchett described her objective as “a character who doesn’t have all the answers, who is 21 and acts 21, and goes through that change throughout the game.” In short: Lara had to learn to like it.

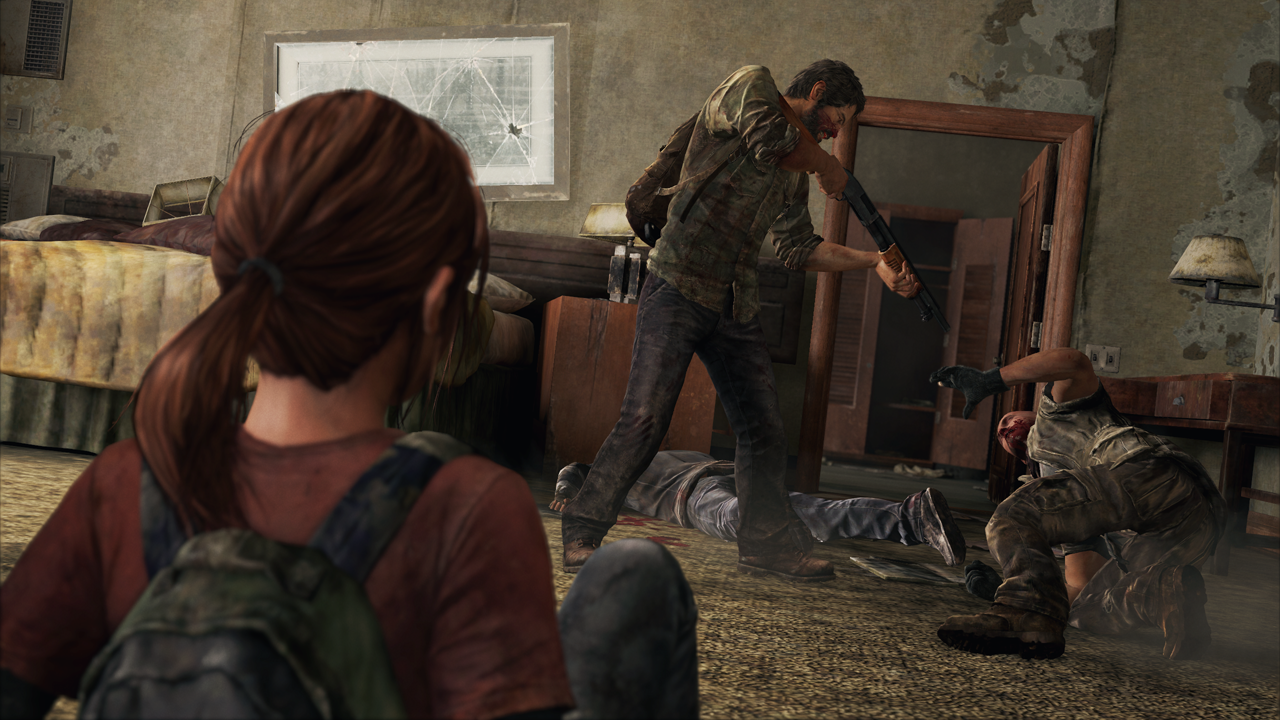

And indeed, ‘learn’ is the pivotal verb in Lara’s latest outing. Her evolution unfolds according to specific and pragmatic educational objectives: how to survive and how to kill. For comparison, The Last of Us, whilst of broadly-similar genre, offers the opposite experience. Joel and Ellie’s journey is about the relationship between Joel and Ellie – not increasing their capacity for killing or even survival. As Joel, allusions to twenty years’-worth of amoral apocalyptic experience inform a character for whom killing in the name of survival already fits like a glove. By the time Ellie ascends to the role of player-character, traveling with Joel has evolved her to a point where her own willingness and ability to kill needn’t be questioned. Everything that is played remains in-sync with everything that is watched, insuring that, at the very least, gameplay and narrative do not undermine one another.

In Tomb Raider, the insistence on tethering the development of Lara’s ease with killing to narrative beats ultimately wreaks havoc with the kind of controlled evolution it wants to show. In general, the game suffers from too abstract a portrayal. Take for instance the notion of survival that the game advertises as its core. Whilst it is an implicit element, it’s not part of the player’s experience. Hunting for food is restricted to a single objective early in the game, and is of greater benefit as a tutorial for the bow rather than a thematic touchstone. Of course, some degree of abstractness is necessary for any work of fiction, we silently acknowledge that Ms. Croft must at some point need to go potty, even if we’re not treated to the experience (My money’s on a cheeky wee in the blood pool ripped from The Descent). But the extent to which this is relied upon to illustrate Lara’s educational development makes for a muddied portrait – and it only gets worse when it comes to her proficiency for killing.

For Pratchett, the speed with which Lara races from Joan Baez to GI Jane is, if not a non-issue, an acceptable contention. In an interview with Kill Screen, she describes Lara’s rather sudden transition to generic convention: “It’s very difficult to keep that good affable character when they’re having to slaughter loads of people. But what we tried to do with Lara was at least have the first death count.” In essence, the emotion behind Lara’s first kill is burdened with carrying the rather rote experience of fighting upwards of five-hundred more men over the following ten hours. Unfortunately for Tomb Raider, its audience is the savviest of the genre-savvy. Where a horror movie has to contend with an audience’s knowledge of well-worn jump-scares and camera-based trickery, Tomb Raider has to contend with the fact that your average gamer is responsible for more fictional deaths than Captain Kirk is illegitimate children. We haven’t walked through the valley of the shadow of death so much as dug it out with our bare hands.

For Pratchett, the speed with which Lara races from Joan Baez to GI Jane is, if not a non-issue, an acceptable contention. In an interview with Kill Screen, she describes Lara’s rather sudden transition to generic convention: “It’s very difficult to keep that good affable character when they’re having to slaughter loads of people. But what we tried to do with Lara was at least have the first death count.” In essence, the emotion behind Lara’s first kill is burdened with carrying the rather rote experience of fighting upwards of five-hundred more men over the following ten hours. Unfortunately for Tomb Raider, its audience is the savviest of the genre-savvy. Where a horror movie has to contend with an audience’s knowledge of well-worn jump-scares and camera-based trickery, Tomb Raider has to contend with the fact that your average gamer is responsible for more fictional deaths than Captain Kirk is illegitimate children. We haven’t walked through the valley of the shadow of death so much as dug it out with our bare hands.

To an extent, the game gets this. When it is finally time for Lara to pop the bloodiest cherry of them all – that of a human male’s precious, precious skull – cutscene turns to quick-time event as it becomes clear that her education must come at the expense of our own involvement. Undeniably, the broader motivation of having the player dispatch enemies in a way that is not so immediately familiar as the point and click kill is a positive one. Nevertheless, it’s not a minute later that the player and Lara are helpfully thrown into bullet-time and rewarded with 100 experience points for nailing two headshots. And with that, it’s all over. The girl who dry-heaved from shooting a man dead is now making eye-sockets explode without breaking a sweat. Forget about the first kill compensating for the five-hundred that follow – it doesn’t compensate for the next two. Simply put, the game’s narrative ambition does not fit into its action-adventure template.

There are two possible responses to this: change the genre or change the story. The Last of Us takes care of the latter: pragmatic education is so fundamentally kept out of its narrative that no such overbearing contention ever rears its ugly head. And then there is DayZ, sat in a dark corner at the other end of the playground, counting down the days with scissors in-hand. Education is an entirely organic process in DayZ, not the singular succession of prescribed events it’s turned into in Tomb Raider. Without a character-arc to fulfill, the player is, for all intents and purposes, playing themselves – their on-screen representative knows as much as they do, is as skilled as they are.

Killing in DayZ is a funny kind of thing. On the one hand, it’s easy to see the game as a kind of drawn-out deathmatch, where a ‘last man standing’ mindset haunts the fields of Chernarus in spite of its inviability. On the other hand, it’s a guilt-ridden episode of ifs and buts: “If only he’d have backed off” and “But what else was I supposed to do?” The reason for the latter is spawned from the context the game provides: you may not actually be killing someone, but you are likely wiping away anything from minutes to entire weeks of their time and progress. Of course, there is also the third, most devious hand, in which your reason is an indulgence of light sadism.

Killing in DayZ is a funny kind of thing. On the one hand, it’s easy to see the game as a kind of drawn-out deathmatch, where a ‘last man standing’ mindset haunts the fields of Chernarus in spite of its inviability. On the other hand, it’s a guilt-ridden episode of ifs and buts: “If only he’d have backed off” and “But what else was I supposed to do?” The reason for the latter is spawned from the context the game provides: you may not actually be killing someone, but you are likely wiping away anything from minutes to entire weeks of their time and progress. Of course, there is also the third, most devious hand, in which your reason is an indulgence of light sadism.

In any case, whatever mindset you enter the game with is your own. If you’re the kind of remorseless fetcher who’s played a bandit from day one and you’re comfortable with shooting someone, then the game doesn’t ask you to pretend otherwise. And it won’t actively guide you towards being nicer, or even more sadistic. Instead it facilitates an environment in which all actions are independently-driven, valid and yet not without consequence. It allows your own evolution in behavior to be guided by your own experiences.

Tomb Raider’s problem is not that it wants to have its cake and eat it. It’s that it wants to have two very different cakes marry each other before eating them both simultaneously. Certainly it’s possible to have a cake of shooty-whizz-bang-fun and very serious seriousness all at once, but it takes more than a shoulder-shove’s worth of insistence to get it working. The central flaw of the game’s premise lies in its belief that it can redefine what it means for a player to kill a video game character just by grunting that that’s what it kind of wants to do. It’s a noble goal for certain, but one that demands greater forethought than Tomb Raider ever saw.

Ethan Woods is a dashingly handsome, thoroughly amateur writer on the videogames, and a student of English and American Literature at the University of London. Prominent fans of his work can find the odd tidbit more at his blog, Ballistically Grapelike.