The Scripted Sequence: Apolitical Cutthroat

Sam Fisher’s knife is a Republican. By Ethan Woods.

Behold, dear reader: before you sits a man enlightened. It used to be that the idea of storytelling through game mechanics would leave a bemused twinkle in my eyes. The concept seemed so wasteful, a surefire way to break entire stories down into metaphors ranking somewhere between ‘Infuriating’ and ‘completely bloody cryptic’. Even I, a connoisseur of storytelling and a savant of abstract metaphors, would not wish for such an all-encompassing transformation. Of course, children are idiots by nature, and by law I was but a child back then, so what can you expect? But no more. My opinion has since been cornered, captured and christened ‘appreciative’. Appreciative of how mechanics might allow us to impart a teeny-tiny piece of ourselves into a character or plot.

Morality is a peculiar thing, don’t you think? Stranger still is how we verbalize it with idioms based in financial logic. If someone does you a favour you ‘owe them’ and if they do you a wrong then you might want to ‘pay them back’. In more relevant terms, we can use this to highlight the United States’ lean to the Right against that of its international chums. In October 2011, Gallup polled Americans on the subject with the question: Are you in favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder? It concluded that “almost three-quarters of Republicans and independents who lean Republican’” were in approval, but only “46% of Democrats and independents who lean Democratic” felt the same way. At the time of writing, 33 of America’s states permit the use of the death penalty, though only half of these are considered to actively use it. The sentiment behind the death penalty and its justification by those who lean to the Right is simple: kill someone and your own life is fair-game. An imbalance on a balance-sheet.

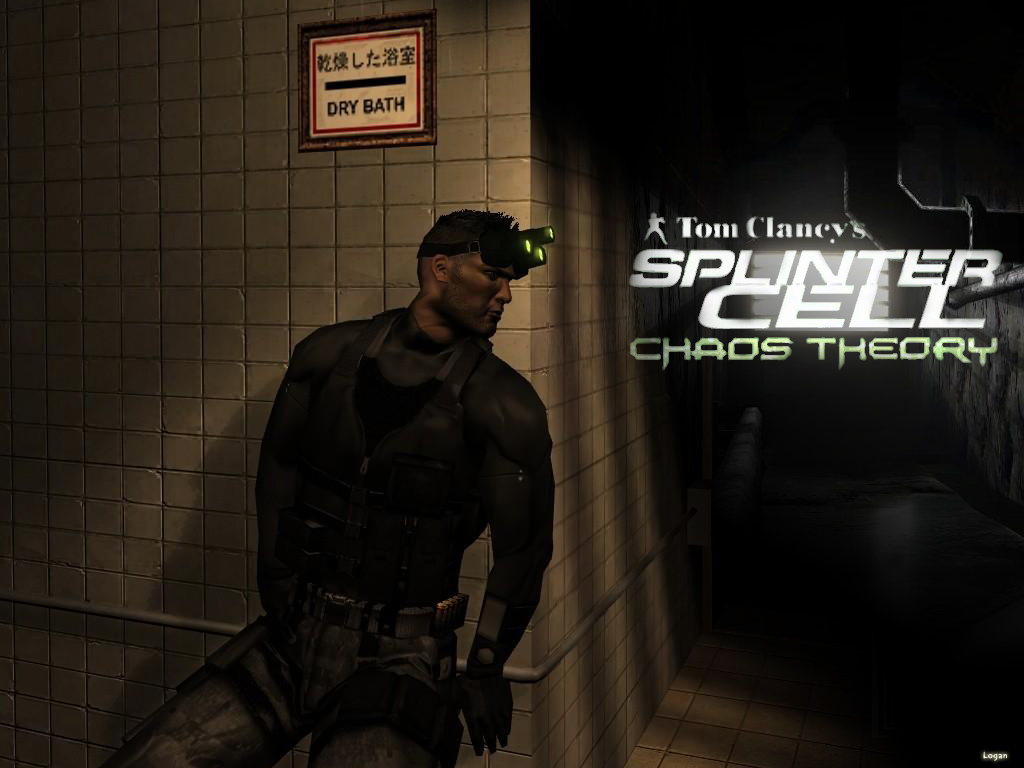

And it’s with that international disconnect that we come to Splinter Cell. Based on the works of author Tom Clancy, an American conservative and product of the Cold War, the series has been a mainstay of triple A gaming since its inception. Unlike Ghost Recon and Rainbow Six, which were first brought to life by Clancy’s own studio, Red Storm Entertainment (long-since Ubisoft Red Storm), Splinter Cell itself has always been developed by Ubisoft. Ubisoft being a studio in Canada, and Canada being death-penalty-free since 1976. Its third and best installment, Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory, was helmed by Clint Hocking, perhaps more widely known for Far Cry 2. Himself a Canadian, Hocking describes himself as “probably more left-leaning […] than the ‘average’ Canadian” who, as he concedes, already have “fairly left-leaning political opinions and moral convictions [relative to Americans]”. Still, despite Chaos Theory’s awkward existence as a property inspired by the works of a conservative American writer and designed by a liberal Canadian, it manages to avert schizophrenia and even uses the ideological dissonance to its advantage.

Sam Fisher himself is an enigma wrapped in a contradiction, sealed in a kinky black wetsuit and hidden behind a voice that’d make Morgan Freeman weak at the knees. Outwardly a cynical military-man perpetually on the edge of a too-old-for-this-shit breakdown, he is in fact a character who has averted crucifixion-by-stereotype. How? Several reasons, voice actor Michael Ironside being not the least of which. But most importantly, from the first Splinter Cell to Double Agent, we’ve had to mine incidental dialogue for clues about the man inside the big rubber condom. Rare is the occasion that Sam appears in a cutscene. We instead learn about him as we play, both through his banter with his team members over the radio and through enemy interrogations. While the latter is akin to the mechanical-storytelling I was rabbiting on about at the beginning, it’s Sam’s shiny new combat knife which is the real champion.

Significantly insignificant, the knife lets us imprint ourselves onto Sam. Our understanding of his character is built from hints, subtle intricacies: his sense of humor, the relationship with his colleagues and his daughter, the absence of a wife. As players it’s left to us to extrapolate any ideological bearings he might have. Our standards for how to progress through a mission may prove reflective of our own attitudes and personalities, but it’s the panicked reactions to crouch-walking Sam face-first into another man’s crotch most accurately define both him and ourselves. To stab or not to stab. Sam’s ‘Fifth Freedom’ allows him to kill without repercussion, so knife use is tied to no rules, except your own. Even civilians can be killed without fear of mission failure, although this does result in a chastising from Sam’s CO Lambert. The choice, the moral justification for our actions, remains almost entirely our own. If your first instinct is to stab, then you imbue Sam with the same financial-logic which is favoured by more Right-leaning people and nations. If not, then like me you are a total hippy. Congratulations. But what really matters is not what choice we make, but that we have the liberty to choose.

As such, Chaos Theory acknowledges and accepts both responses. The refusal to enshrine them within Sam reflects the moralistic dissonance between nations and even countrymen, between those inspiring, creating and playing the game. Neither reaction is given moral superiority, with any mechanical superiority (like kills reducing your stealth-rating) being divined from a practical realm of logic. Not only does Sam’s knife come to nullify any ideological friction, but it allows us as players to actively impart him with our own culture; our own life experiences and attitudes in a way that, seven years later, remains all too rarely seen within gaming. The series’ latest efforts may have been an attempt to make him more recognisably human, but it’ll forever be Sam’s knife that helped make him the character he is to me.

Ethan Woods is a dashingly handsome, thoroughly amateur writer on the videogames, and a student of English and American Literature at the University of London. Prominent fans of his work can find the odd tidbit more at his blog, Ballistically Grapelike.