Let’s Play a Love Game: Depths (and Shallows) of Monstrosity

Eric Cline embraces the monster inside.

Spend any amount of time around gay people and you’re likely to learn about their love of monsters. Many a Twitter thread has been written addressing this shared demographic interest, speculating about gay people’s ability to relate with outcasts and general deviance from societal norms. Alternatively, one might sum up the appeal as such: monsters are just fucking cool.

It’s no surprise then that there’s been a boom in recent years of queer-made and queer-oriented media, and more specifically dating sims, starring monsters. These highlight queer people’s attraction to the monstrous on romantic, sexual, and thematic levels. The potential for success and failure in this concept lies within a conundrum: how does one portray monstrousness as desirable while still preserving monstrousness itself? The concept, abstract though it may be, is inherently rooted in deviation, rejection, and an overall sense of otherness. How does one pursue the undesirable without stripping it of all grit and substance in some sort of paranormal smol-beanification?

These were the questions at hand as I booted up Monster Prom XXL. A 2020 updated version of 2018’s original Monster Prom, it features all of the prior game’s content as well as new romanceable characters and scenarios. In both games players take on the roles of students at Spooky High, a school whose pupils are monstrous not only in their species and design but also their general lack of respect for social order. Romanceable characters include a werewolf, vampire, mermaid, demon, eldritch abomination, and more.

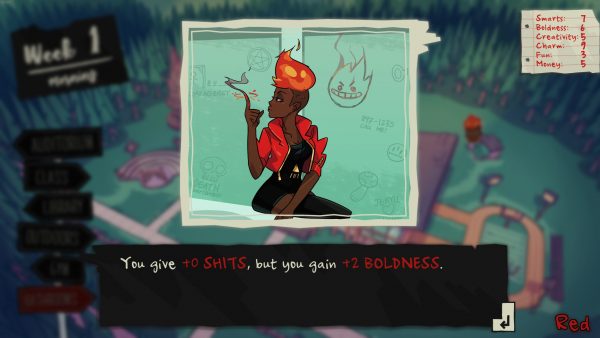

Gameplay-wise, players have a set number of weeks to court their monsters of choice. This involves not just choosing between various dialogue options but also raising specific stats through school activities such as attending classes, going to the library, or spending whole periods truant in the bathroom. At the very end of the game players choose a monster peer to ask out to prom, and success depends upon meeting thresholds for general affinity and compatible stats. In other words, standard dating sim framework.

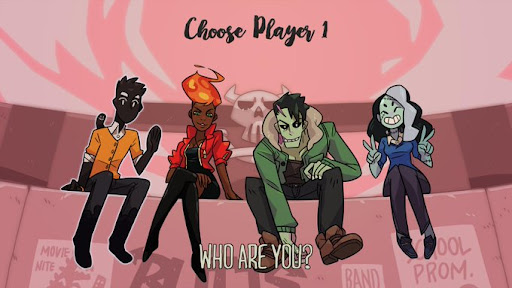

Monster Prom’s approach to otherness comes through clearly from the opening player selection screen. Many dating sims with flamboyant romantic leads contrast them with more mellow player inserts ala the human protagonists in Hatoful Boyfriend and Obey Me!, which are games centered around courting birds and demons respectively. Not so here. Players are presented with four characters to serve as their avatar in-game, each of whom is as monstrous as the fellow students they end up dating.

The primary implication here is that the player character is at home on their own turf, not ostracized for their bolts, ectoplasm, or whatever the case may be. Though the characters differ in their specific origins and brands of monstrosity, none of them would fit within the confines of a standard slice-of-life dating sim. To be a monster within the world of Monster Prom XXL is typical, rather than an anomaly.

Therein lies the potential for thematic incongruity, however. Above all else, monstrosity is a state of deviation. It is the rejection of norms, whether consciously and deliberately or by nature of intrinsically existing outside societal expectations. Without an in-group (i.e. humans) to be compared to, the characters don’t actually deviate from an established norm within the game itself.

As a result, their monstrousness must be viewed within the context of real world expectations and aesthetics. In this sense the characters are monstrous: with fangs, horns, and tentacles in large supply, they are largely reminiscent of the literary and mythological creatures that many queer people have found semblances of themselves in. They are proxies of proxies, distortions of images which were themselves crafted in opposition to and in reflection of audiences.

This mirroring of character and audience extends into Monster Prom XXL’s tone. The monsters of Spooky High approach their danger-laden lives in much the same way as their gay, controller-holding admirers: with humor. First and foremost, Monster Prom is a comedy. While day-to-day interactions provide insights into characters’ personalities and the state of monster affairs, all such developments are second to the game’s preoccupation with keeping up a steady flow of gags.

It’s here that the game most successfully highlights its characters as being monstrous on a level deeper than the purely aesthetic. This being a dating sim, there’s an obvious imperative for the characters to be likable and thus make players interested enough to bother playing the game in the hopes of receiving a “Yes” to their prom invitations. With that said, if the characters are going to feel like monsters, they need to be allowed to act cruelly, selfishly, and abrasively.

How to pull this off? With dramatic, dry, and often vicious wit defined by a consistent lack of respect for authority. While the characters’ actions would certainly be extreme and inexcusable in a real life setting, metaphorically speaking their motivations (whether driven by disrespect, feelings of inadequacy, or misdirected rage) are frequently relatable. While a bigoted asshole can lurk around any corner, it’s the often subtle ones in day-to-day life (i.e. in class, at practice, at work, or otherwise among one’s peers) who are the most frequently distressing.

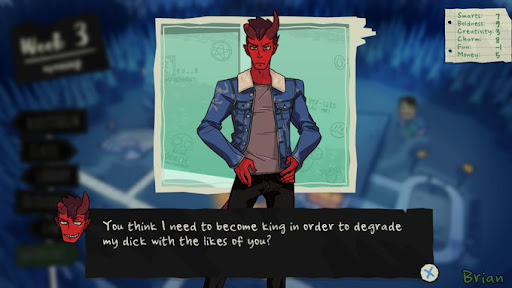

With that in mind, let’s consider my paramour of choice: Damien, a literal pyromaniac prince of Hell. He is bluntly outspoken when he reviles something (or someone) and revels in property damage. His sexual interests explicitly include butt stuff (because God seems to especially hate butt stuff), and though he’s more than a little prickly he’s not above being honest about his feelings when he does like someone. On one hand, he’s the (demon) personification of “Don’t you just wanna go ape shit?” On the other, his aggression stems largely from the expectations and irritations of a world that simply doesn’t match his own desires. (He didn’t exactly ask to be born prince of Hell, after all.)

Beyond being relatable and rooted in something real, Damien’s rudeness (and that of the other characters) also betrays a fact that is pivotal to the game’s success: sometimes mean-spiritedness is fun! If one asks a character out to prom without meeting their stat prerequisites or otherwise displeases them along the way, the rebuttal is not gentle. Take for instance one of my favorite moments in the entire game, in which I felt like an Animal Crossing villager under the sort of fire you just don’t see anymore in that series’ modern releases:

There is a willingness here on behalf of the game developers to let the romanceable characters be not just morally gray but outright mean and terrible, celebrating the fun that can come with being a monster. When I was first abrasively, yet humorously rebuked after pronouncing my affections by Damien, I was as happy as I would have been (if not more so) had I received reciprocity. One of the defining aspects of gay adulthood for me personally has been learning to set boundaries in such a way as to put my own contentment above that of people with narrowminded views, i.e. bigots who would view me through the lens of monstrosity cast by homophobia. While most of the harsh words in Monster Prom XXL concern less serious topics, it’s still nice to see outcast characters who understand their own needs and don’t shrink themselves.

Unfortunately, the further one follows the implications of metaphor, the clearer it becomes that Monster Prom XXL’s depictions of monstrosity are shallow in nature. The game gets off to a great start, acknowledging players’ desires to embrace their own monstrous sides rather than stay on the outside looking in. From there, the game even makes room for the mixture of humor and disdain that many people (particularly fork-tongued gay men) use to navigate their days. What’s missing, however, is analysis of how being deemed monstrous can impact the monsters and their relationships.

Take, for instance, Scott: the resident werewolf boyfriend. Sure, his buff, overly hairy body might be attractive to many gay men. It’s the metaphorical aspects of werewolves that are most interesting, however: a psyche eternally defined by the conflict between two clashing selves, and a state of being that always comes back to the surface no matter how much the afflicted might want it to stay buried. With Scott however, no such character depth is present. Regardless of what choices the player makes, Scott will always remain confined to a kind but dim archetype. This sort of limitation hinders the other characters’ arcs as well, including Damien’s. While his backstory as a prince of Hell has meat for exploration, he’s given very little time to actually address it directly and discuss what his regrets about it look like on a day-to-day basis.

Monstrosity can be humanizing, and tied to interpersonal relationships and conflicts. Monster Prom XXL attempts, however, to preserve it within the context of a larger community that features virtually no other norms to deviate from. There’s something to be said for fostering community among outcasts, but true community cannot be built without taking the time to get to know the individuals it is made up of. With every scene constructed to deliver a comedic payoff, there’s little opportunity for the characters to let their guard down and be vulnerable.

Humor, so useful in real life as a means of coping with trauma, has only stifled both intimacy and any actual theory of monstrousness itself beyond aesthetic signifiers in this game. Thus, the characters’ relationship to the audience becomes a funhouse mirror: a reflection, yes, but one so distorted it’s no longer useful as a means of seeing the original for what it truly is.

Eric Cline is a writer from the NOVA area. He is a columnist for Haywire Magazine, manga/anime section editor for AiPT! Comics, poetry editor for Angel Rust Mag, and co-host of the podcasts Queering the Guillotine and Chris and Eric’s Longbox Adventure. You can find him on Twitter @ZorakRichardson.