Due Diligence: The Mass Effect Andromeda Trilogy, Part III: Lost in the Wilderness

Leigh Harrison explores samey new worlds.

In the sci-fi miniseries Devs, tech entrepreneur Forest (a haunting Nick Offerman) loses his absolute shit after hearing Jesus speak. By feeding a quantum computer all the data we currently possess on everything, his team is able to effectively predict the past. It’s not actually Jesus speaking, rather a representation of what he would have sounded like. A representation, however, so accurate that it may as well be time travel. But Forest isn’t happy.

The prediction model is based on the Everett interpretation of quantum mechanics. In short: every possible outcome to every possible event exists in some world or universe, somewhere. The Jesus speaking to Forest is the real Jesus, just from an alternate timeline. It isn’t Forest’s Jesus, and that’s why he isn’t having any of it.

Procedurally generated video games make me feel exactly the same way.

I have this disconnect with procgen that can only be described as mild revulsion. It unnerves me, and I just cannot connect with games that use it. To oversimplify, they’re a collection of assets and mechanics assembled by algorithm. There’s always this nagging feeling that if what I’m seeing exists for me alone, then it shouldn’t really exist at all. Where’s the meaning if what I’m playing is created by chance?

I appreciate this is a reductive—entirely incorrect, even—opinion to hold, but it lives in my gut, not my head. What I really mean when I say it has to be my Jesus, is that it has to be everyone’s Jesus. A game built by human hands that provides a singular, authored experience. As I said, this feeling lives in my gut.

In Jason Schrier’s retrospective on the making of the fourth Mass Effect game, he tells how Andromeda was initially planned to rely heavily on procgen. It would have “featured hundreds of explorable planets” and used “algorithms to procedurally generate each world in the game, allowing for near-infinite possibilities, No Man’s Sky style.” As I’ve mentioned before, I like NMS as much as anyone. But I don’t find excitement in that promise of near-infinite possibilities. At the risk of slipping into Devs-isms: if you have everything, you have nothing.

That nihilistic black hole worked perfectly for vanilla NMS, which I read to be about the emptiness of infinity. It was a brave and radical stance, one that has since been eroded through the grafting of more game onto its once barren experience. But a procgen Mass Effect, with all its story, characters, and relationships. That’d never work, surely?

It didn’t.

In the end, everything in Andromeda was made by hand. Not that I can really tell when I’m down on the surface of the game’s six planets. Four are bloody massive, one feels empty and unfinished, and the other is tiny and could have come from a different game. What they all have in common, though, is the eerie sense of procgen about them.

The best open worlds have recognizable landmarks, topography, and so on, which provide players with a sense of place and orientation. Skyrim opens with me stranded at the head of a mountain trail. At any point I could choose to deviate from its sinuous route, but each bend in the valley offers new sights. First, a small garrison, then the hamlet of Riverwood, later, marvelous waterfalls. I’m led by the nose by these points of interest, until all at once the path opens onto a gigantic glacial plane, the valley walls perfectly framing the town of Whiterun, perched atop a rocky outcrop in the distance.

Every race in Burnout Paradise ends in one of eight locations. These repeated visits mean I quickly begin to map the areas around them in my mind, and after a few races I’ve already built up a good understanding of the game’s road layout. Grove Street is an important location early on in GTA: San Andreas, that seems impossible not to find. It occupies a central location on the map, and is bordered on all four sides by wildly different land use. Whether I’m approaching from the freeway, river, docks, or residential streets—or, indeed, heading to those areas from further afield—I always know which direction to travel in to get to Grove Street.

Environmental features can be used to great effect in directing players and helping to acquaint them with their surroundings. And whether we’re talking about sweeping landscapes or urban sprawls, these sorts of things are so perfect they almost never occur organically, and they aren’t accidental in games. They’re authored to create memorable—and navigable—landscapes.

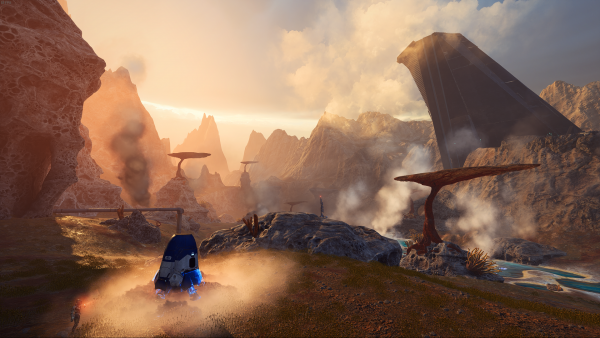

Andromeda has none of this. Its planets are giant smudges of anonymous terrain with nothing for the eye to hold on to. No clever lines of sight or subtle cues in the landscape. They’re so bland it’s difficult to reconcile that a team of talented designers produced them. But one can’t mistake them for naturally-occurring landmasses, sucked into the game from real-world map data, either.

They’re too erratic, too computer-y. Mountains abruptly rise from flat plains with near-vertical slopes. Sheer cliffs meet at equally sheer right angles. Ridges are as sharp as knives. These spaces lack any defining features save for, perhaps, their uncanny valleys. They are voids.

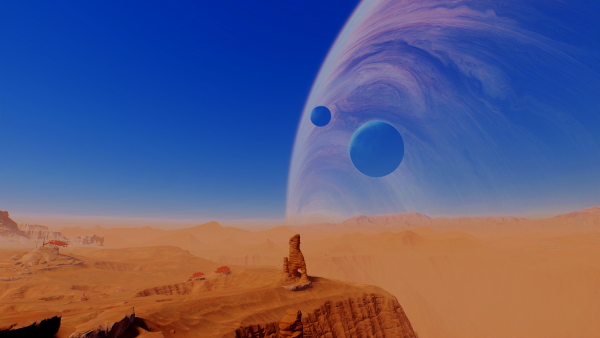

I’m on the game’s starting planet, Eos, looking for something to do. I scan the horizon for a new objective, but it’s useless. The world is an arid wasteland of sand dunes and ancient, weathered cliffs. Eos is pretty low on landmarks save for the Andromeda Initiative outpost of Prodromos, which itself is less a town than a collection of haphazard prefabs. Sure, there are the facilities and bases and ancient Remnant sites literally everywhere, but they’re even more anonymous than Prodro.

I pop open my omni-tool to make the job easier. As I flick through the menus I’m reminded of long-forgotten tasks. Photographing rocks on Voeld. Securing medical caches on Elaaden. Catching insects on Havarl. Aren’t I meant to be charting new worlds and meeting alien species? I did do some of that early on, to be fair, but further in there’s an awful lot of fetch quests. All I really do is dash from planet to planet, picking stuff up from hillsides. It’s always hillsides. Every planet is like bastard Scotland.

They’re not even good hills; they only exist to mask loading. There’s a lot of driving in Andromeda, and the inclines are there to slow me down for long enough to let whatever’s at the top have time to load into existence. Getting anywhere is this really fractured process of driving at full pelt for 20 seconds, then inching my way up a slope for another 10. Each planet is stitched together like this and it makes getting around thoroughly monotonous.

My other issue with the worlds is how visually monotonous they are. In screenshots, they’re quite beautiful—especially the textures, lighting, and art direction—but each planet is a single, uniform biome. There is a beauty to Eos’ dusty amber expanse, but after many hours the endless dunes numb the senses. The other planets are like playing video game level bingo. There’s the ice world, the jungle, the asteroid, the other desert—seriously, what game needs two massive deserts? Then there’s Kadara. I was taken aback when I first landed there, impressed by its stark, almost Icelandic tundra landscape. Now, I never want to set foot there again.

It’s the classic stratified society setup: a wealthy upper city of trade and commerce atop an underslum controlled through fear and violence. Past the slums is the Wasteland; miles upon miles of mountainous terrain peppered with the same prefabs that make up Prodromos—that make up every Initiative building in the game. (I actually quite like the narrative conceit for this, that everything’s built from easily-transported materials that had to be brought from another galaxy. But it does get a bit samey after a while.)

I would say a good quarter of Andromeda’s smaller quests take place in the Kadara Wasteland. In each one of those little prefabs sits a person or item I need to visit, sometimes more than once. These quests pop up all throughout the game, across many, many hours. But I can’t land my ship in the Wasteland. I have to first visit the upper city, then ride a loading screen elevator to the slums, run through them to get to a forward station, and then call my NOMAD so I can drive up and down 1,000 hills to get anywhere, because Kadara is by far the worst planet at hiding loading screens in plain sight. It’s like the setting for every Brontë novel smooshed into one massive, soul crushing moorland.

If reports are accurate, creating Andromeda was a hellish experience for those involved. Shifting goalposts and upper management egos led to huge swathes of work being dumped and started again. The game I’m playing was reportedly made in little more than 18 months of the five year development cycle. It’s not hard to believe this, looking at Eos, Kadara, and the rest. They’re slapdash; hunks of land that are functional yet woefully underdesigned, as if they were assembled at the end of a four month work week. I don’t think this is beyond the realm of possibility.

The conventional wisdom around Andromeda is that it is an unmitigated disaster, irredeemable by any measure. I disagree with this sentiment wholeheartedly. I think it’s a game made by people royally fucked by a means of production that doesn’t really work. Years of indecision and grandstanding at the top, combined with an, I would imagine, immovable release date conspicuously close to the end of the fiscal quarter, left Andromeda to die as if that was the plan all along.

The levels in this video game are bad. But I don’t for a second believe this is because the people who made them can’t do better. This hasn’t been an exercise in shitting on the labor of overstretched workers. Andromeda, like Anthem after it, is a document of what happens when a publisher cuts its losses and rushes a troubled production to market. I’m sure there are business reasons for doing so, but from an artistic and humanistic perspective I find it unforgivable.

I admire Andromeda because it dares to try. To take the series in a new direction. To add nuance to character interactions. To build its own identity. If only it’d been given a little more time to make up for those difficult early years, who knows how differently things would have turned out? Instead, hundreds of people saw their work met with glib gifs and inexcusable harassment.

The truly heartbreaking thing is that, even with everything that happened during and after its development, Andromeda comes pretty close to achieving its ambitions. So, for the remainder of what’s turning into a five or six part trilogy, I’ll be digging into these successes. Mass Effect: Andromeda is a good game. A special game. It’s about time it got its dues.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, and works in communications for a medical charity. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.