Art Tickles: The Very Worst

Taylor Hidalgo finds good guys are only “good” from one perspective.

“You must redeem yourself.”

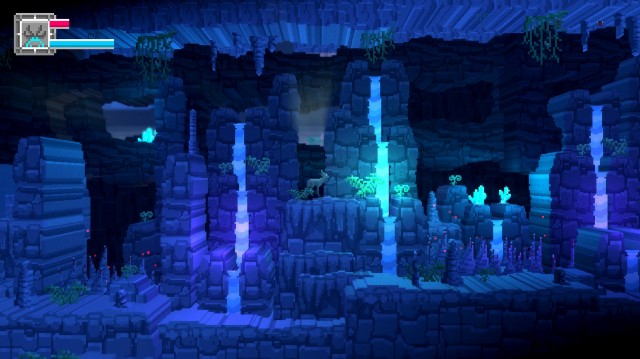

These four words are how The Deer God begins, demanding retribution from a hunter that inadvertently shoots and kills a fawn as he is killed himself. In the afterlife, he is visited by the Deer God, a large and deistic quadruped that informs him he must atone for his transgressions against deer-kind. A fair assessment; It stands to reason a hunter would have a larger than average karmic toll to pay to a powerful deity of the woodlands. Especially for as much damage as hunters can do to the natural order.

Forced into a quest for redemption, the hunter is transformed into a buck, and set loose into the forest. Though sent to atone, the Deer God never fully explains how the hunter is meant to do so. Without much more than a few moments’ preamble, the hunter-deer is dropped back into the world to make his own way forward. For the player and hunter alike, this means being lost in the woods from the very beginning.

As the game unfolds, certain traits are taught and enforced early. Many of the smaller, cuter woodland creatures are desperately vulnerable. If they decide to follow the player, which they’ll often do, they’ll be putting themselves at grave risk. When they die, they explode in a spectrum of angry red, an ephemeral mist that drifts into the sky, where it is tallied against the player’s karma. Any creature that does not attack the player is one the Deer God tacitly expects the player to defend, save, and protect. Even from themselves.

The death of any hostile creatures, however, results in “kind” karma, and positive movement for the game’s protagonist: tacit proof that the hunter has learned his responsibility to the natural order, and is willing to do his part to improve the woods, and ultimately, earn his redemption. Players who actively hunt hostile creatures, and kill them, will be rewarded with large amounts of positive karma.

From a mechanical perspective, the idea of passive creatures being “good guys” and hostile creatures being “bad guys” fits rather well. Saving stags, does, and fawns would naturally be encouraged by the morality of the Deer God. However, the indiscriminate slaying of foxes, ravens, mountain lions, hogs, rhinos, and hostile stags doesn’t exactly fit. The natural order of the forest, or any enclosed biome, depends on balance. Everything needs to be alive in order for the full ecosystem to thrive. This stands in harsh contrast to the selective, Deer-God-endorsed murder of hostile creatures. Even hunters, for as much damage as they do to the animal populations, are still a part of a grander and vaster system.

For the Deer God, a literal god, to be so short-sighted on how a world collectively weighs on the karmic scale, doesn’t seem to fit. However, if the player so chooses, they can murder their way into kindness and good graces. A death-centered kindness is apparently on the moral spectrum of the Deer God. Which certainly doesn’t match a hunter atoning for the sin of murdering a forest creature.

Perhaps because moral choices don’t exist in a vacuum. Moral choices, like those infamously found in BioWare games, are often predisposed behaviors which conform to the majority of players’ beliefs on “good” and “evil.”

A player who wishes to max out their dark side will rob from starving families, kill incompetent lackeys, lie and cheat as a matter of reflex, and use their power to gain advantage over those weaker. In a dog-eat-dog world, the only room for kindness is on the losing side, the exploited rather than the exploiters.

Good, on the opposite hand, is often tailored to be unimpeachable and impeccable. Sharing limited resources, investing time in helping others, offering anything to another for nothing in return, and preventing the power-hungry strong from abusing the cowering weak. Each of these are the behaviors of a universally-understood “good” character. A guideline to insure that their behavior cannot be mistaken by anyone to be “evil.”

By that moral system, there is no room for villainy in a good character, nor is there room for goodness in an evil character. They’re caricatures: they don’t represent actual humanity or morality in any realistic form. It’s a shorthand to insure that any behavior, good or evil, cannot be mistaken by anyone to be anything other than its intent. Evil people do comically evil things, and good people do excessively good things. They leave no room for doubt.

The true monsters in life, those that use and abuse alike, don’t do so while twirling Saturday morning cartoon mustaches and plotting which small animal to kick next. Most evil people are evil in the sense that their beliefs reinforce their villainy. Their behaviors are more nebulous, often justified by some belief system or guiding ethic that spurs them forward. It isn’t about doing evil for the sake of doing evil, but acting toward an end which justified the means. The very worst sort of monster considers himself a hero.

So as the hunter-deer smashes his antlers into a winter fox, crushing its skull and discarding the broken remains in a flash of karmic blue, the true shape of a monster begins to appear. A truly efficient hunter, one that capitalizes on every opportunity to earn kindness karma from the Deer God, is one that systematically hunts and kills the hostile animals. It isn’t about restoring balance or defending the innocent, it’s about slaying the opposition. Whether the opposition is a hunter, or a rhino defending its territory from invading stags, the death of opposition is death celebrated and rewarded by the Deer God.

Why this particular hunter gets the chance for karmic redemption rather than other presumed hostile forces, or why the death of any hostile animals—even other stags—is seen as positive is never remarked upon. The player’s redemption is contingent on the morality of the Deer God, but whether or not these murders are “good” actually has very little to do with what is morally right, and much more to do with what the Deer God deems worthy. In the process of growing the Deer God’s positive karma, there’s little doubt that the hunter will have killed more as a deer than in his former life as a hunter.

As a hero of the Deer God, redemption comes at a high price. Abilities often come with the expectation to fight, to engage, to defend, and to destroy. In the process, many allies will be inadvertently killed, many otherwise innocent animals will be slaughtered, and the true face of a monster will often seem far more deer-like than the opening cutscene implies. In nature, the strongest kill and survive while the weak starve and die.

In light of that clinical terminality, the Deer God’s actions begin to take a different pattern. This isn’t about redemption, it’s about retribution. It’s about mastering the forest for the benefit of the Deer God. “You must redeem yourself” is good in theory, but under whose rules is this redemption determined? The wolves that fed on his body certainly saw no foul in killing him for his meat. The fawns that followed him to their deaths gained nothing from his quest for redemption. The indigenous animals that were killed gained nothing but death for their troubles.

Prudent hunters should be wary of how they seek redemption lest they become monsters themselves. Morality is never so simple as black or white, there are just different shades, and the shadows cast by those who consider themselves the highest, are often also the longest.

A copy of The Deer God was provided by publisher Crescent Moon Games.

Taylor Hidalgo is a freelance writer, ever longing for work. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games, and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter and his website, and has a Patreon if that’s your thing.