The Parable of Joel: Practicing Empathy in The Last of Us

Brook Johnson asks us to reconsider a misunderstood character.

Watch out – this article contains spoilers about the ending of The Last of Us.

Joel and Ellie’s struggle to preserve their humanity in a vicious post-apocalyptic world creates a strong empathetic bond between the characters and the player. By experiencing their world vicariously, I recognized its horror. Joel and Ellie face morally ambiguous decisions with no good alternatives. Throughout their journey, Joel and Ellie consistently enact violence in order to survive. Joel strangles enemies caught unaware; bludgeons infected humans with baseball bats, and decapitates survivors with shotgun blasts. These gruesome kills can be unsettling, but Joel and Ellie’s violent acts are never trivialized or cheap. The player sees the world through their eyes by directly controlling the savagery of their actions and witnessing that of their adversaries. While Joel and Ellie’s journey creates empathy, Joel’s endgame decisions test the empathetic bond between his character and the player. Unless we take an empathetic perspective on Joel’s character, I don’t think we can fully understand the ethical complexities of Joel’s often controversial decisions.

In the game’s final act, doctors from the radical paramilitary collective known as the Fireflies hope to utilize Ellie’s immunity to create a cure for humanity, but the operation will kill Ellie. The Fireflies’ leader Marlene gives Joel two options: leave the premises or die. Joel rejects Marlene’s options and chooses to save Ellie, but in the process kills Marlene and two Firefly doctors (along with numerous Firefly soldiers, depending upon the playthrough), and later lies to Ellie about all that had transpired while she was unconscious. Jason Sheehan, Ed Smith, and Reid McCarter concur: Joel’s decision to save Ellie is problematic. Sheehan thinks killing Ellie is a necessary condition to save humanity. McCarter labels Joel’s decision to save Ellie as “selfish.” Smith believes Joel’s lie to Ellie is ultimately “self-serving.”

While it may be tempting to assume that killing Ellie is a necessary condition to save humanity, The Last of Us makes no such universal claims. Marlene insists “there is no one else,” and killing Ellie is the only choice. We are left to speculate on the veracity of her claims. Needless to say, Joel’s decision to save Ellie does not necessarily eliminate a cure from being developed; he only eliminates Ellie’s immunity from being reverse-engineered via the Firefly operation. Rather than determine whether Ellie’s immunity is or is not necessary to save humanity, or whether the Firefly operation would have been successful, which The Last of Us does not explicitly comment upon, I think critics’ negative perception of Joel will change if we reframe Joel’s problematic decision with an emphasis on his character growth. Part of empathizing with Joel involves entering into his transformative journey.

At the beginning of the story, Joel loses his only daughter Sarah to a chilling utilitarian precaution enacted by the American military. Twenty years later, Joel’s grief is evidently buried beneath his will to survive in a milieu of hostile, manipulative survivors where one’s very existence depends upon enacting violence. Pessimism and self-interest mark Joel. He adamantly opposes Marlene’s plan of transporting Ellie to the Firefly HQ. Joel wants the weapons and supplies promised by the Fireflies—nothing more. Throughout the early chapters, Joel is uncommunicative, bitter, and responds harshly to Ellie’s inquisitive nature. Joel considers Ellie a burden to unload on his brother Tommy, despite Ellie’s protests. The shouting match between Joel and Ellie in a ranch house late into their journey marks the turning point. It is here, in the midst of Ellie’s rebellion and Joel’s hurt indignation, that we see how much Joel cares for Ellie’s well-being, even when his words say otherwise: “You’re not my daughter, and I sure as hell ain’t your dad. And we are going our separate ways.” Joel and Ellie do not separate. Instead of leaving Ellie with Tommy, Joel takes her to the University of Eastern Colorado to continue their search for the Fireflies. Ellie is no longer merely an object for Joel to begrudgingly transport across the country: she is a human being—like Sarah. Joel’s transformation from a self-centered cynic back to a caring father occurs after numerous near-death experiences, a harrowing escape from the University, and Ellie’s care for him at Silver Lake. Here, Joel risks his life to rescue Ellie from cannibalistic survivors, and their cathartic embrace following David’s death illustrates the profound depths of their father-daughter bond. Joel recognizes Ellie’s unquantifiable worth as a human being. In a sense, Joel comes full-circle.

Formerly, Joel may have shared Marlene’s frigid view that killing Ellie is the only choice. But Joel’s scathing reply, “You keep telling yourself that bullshit,” suggests his transformed character. For Marlene, there is no other proper choice. Ellie must be sacrificed so that humanity might be saved. But for Joel, sacrificing Ellie is not the answer to humanity’s problems. Joel has rediscovered the value of an individual human life: Ellie cannot be reduced to a number. His evaluative reply demonstrates his refusal to join the barbarism into which humanity has descended. Joel takes the moral high ground with his implicit comment on Marlene’s decision: Ellie’s life is of such great value that killing her to possibly save many will turn humanity into the very monstrous creatures they desperately hope to eliminate. We can understand Joel’s decision to save Ellie when we recognize his dramatic character growth. However, is Joel selfish for refusing to sacrifice the life of one for the lives of many?

My short answer is no. The Firefly doctors show a blatant disregard for human agency and reduce Ellie to a numeric value all in the service of bringing about the greater good. It is too simplistic to view Joel’s decision to save Ellie through the utilitarian lens of one life for possibly many lives. There are three problems with the Fireflies’ utilitarian view that need to be addressed.

First, we are not in an appropriate epistemic position to foresee the net consequences of our actions. The Fireflies may have killed Ellie and still found themselves unable to produce a vaccine. That is a chance Joel cannot take: he could not protect his own daughter, but he will protect Ellie. Perhaps saving Ellie will bring about the greater good. Who can know? It is wiser to investigate all possible alternatives instead of hastily concluding in the span of an afternoon, as the Fireflies do, that taking Ellie’s life nonconsensually is the only choice. Second, there are some things you cannot do to people, no matter the outcome. For me, extinguishing Ellie’s life without informing her of the operation’s terminal intentions falls into that category. Joel’s actions suggest his agreement. Third, the utilitarian view does not account for the parental obligation one has to their child. We have a responsibility for the life and well-being of the child in our care. If I were in Joel’s position, would I really allow my surrogate daughter to be killed by this radical organization, so that some greater good might result? I would not. Like Joel, I recognize the parental obligation he has to protect Ellie from harm. Joel’s decision is messy, and it will have consequences of its own, but I do not think Joel is selfish for opposing Marlene’s brutal calculation. Nevertheless, Marlene’s comment on Ellie’s desires warrants discussion.

During Marlene’s final confrontation with Joel, she asserts, “This is what she [Ellie] would have wanted, and you know it.” Now, Marlene is probably correct. Ellie’s desire from the beginning of the story has been to assist in developing a cure for humanity. Joel kills Marlene and rationalizes his decision by claiming that she would come after Ellie if he allowed her to live. Multiple psychological motivations seem to be at work in Joel’s decision. Killing Marlene may result from Joel’s survivor mentality: kill or be killed. Or maybe Joel, in the moment, thought killing Marlene was necessary to protect Ellie. Or perhaps killing Marlene was the only way for Joel to fully vent his rage and contempt for an operation that he finds morally detestable. Alternatively, Joel’s parental fear for Ellie’s well-being could have temporally overpowered his rational faculties. Taken collectively, I think these motivations (and likely quite a few more) serve as grounds for understanding Joel’s behavior. Joel does not kill Marlene with wholly pure intentions, but somewhere in this convulsive mix of intersecting beliefs, fears, and desires, I find a flawed human being who I cannot bring myself to indict. Still, does Joel go too far when he prevents Ellie from sacrificing herself?

Ellie’s deep unconscious desire may be to sacrifice herself for the greater good of mankind. She is mature beyond her years, intelligent, rational, entirely capable, and displays a remarkable sensitivity to the world around her. If Ellie was conscious, it is likely that she would have agreed to the operation. But the Fireflies do not give her the choice. Ellie is in a vulnerable state which the Fireflies are eager to exploit. The emphasis of this sequence centers on Joel’s decision to save Ellie from what he perceives as a morally compromised operation. If the Fireflies had allowed Ellie to choose, and she chose to sacrifice herself; Joel’s decision to save her would be blameworthy: Joel would have violated Ellie’s autonomy. Instead, the Fireflies deliberately violate Ellie’s autonomy by operating on her without consent, which impels Joel to save Ellie. Joel’s decision is not like the Fireflies’ violation. His decision is instinctual, parentally obligated, and care-oriented. Apart from speculation involving whether Joel could or could not have postponed the operation until Ellie was conscious, we are left with the Fireflies’ reckless disregard for human choice and Joel’s care for Ellie’s well-being.

After departing the Fireflies’ HQ, Joel lies to Ellie by claiming there were “dozens” of immune survivors like her, and their immunity was insufficient to produce a cure. The Fireflies, says Joel, “have stopped looking for a cure.” The question must be asked, beneath the veneer of caring for Ellie, is Joel’s lie to her ultimately “self-serving?”

No doubt, it’s a questionable decision. There appears to be something self-serving in his lie. Joel wants to preserve his relationship with Ellie: he cannot bear to lose a second daughter. But if we are to gain a deeper perspective on Joel’s character, we must supply the equally plausible motivation that Joel’s lie comes from his overly protective desire to shield Ellie from survivor’s guilt. That is, Joel’s motivation to lie is partly based on caring for the emotional state of someone outside himself. If we are to empathize at all with Joel’s messy, even ugly decision to lie to Ellie, it is because we recognize that Joel has come to love Ellie, and love her in a way that he was previously incapable of.

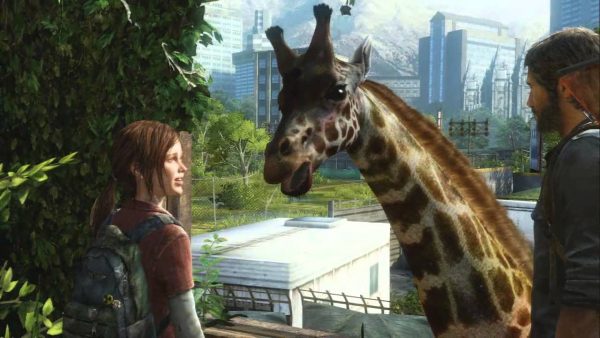

In Salt Lake City, hours before encountering the Fireflies, Joel and Ellie observe a herd of grazing giraffes. Joel uses the playful term “kiddo” to refer to Ellie, and they pet a giraffe together. For the first time in the story Joel seems content:“This everything you’ve been hoping for?” he asks. Ellie obviously hopes for more than giraffes, but she smiles and looks at him sideways, and says, “It has its ups and downs. But you can’t deny the view though.” Joel and Ellie’s journey has been one of continual ups and downs in their relationship, friendships, acquaintances, safety, and health. But through these shared, private moments, they’ve become inseparable. Unfortunately for Ellie, Joel is all too human.

Joel’s love for Ellie is mixed up in the tangled web of self-focused needs and charitable desires that we share as human beings. Those of us who empathize with Joel will recognize these same needs and desires in Joel’s behavior throughout the story. I do not propose to rationalize Joel’s lie or even excuse it. But when I view his lie from the perspective of a human being desperate to protect Ellie’s emotional state, hopelessly entangled with his own need to love and be loved, I would no longer characterize Joel’s lie as ultimately “self-serving.” It is both self-focused and other-focused, and any attempt to separate the two inevitably reduces Joel’s character.

Brook Johnson is an English Major at Tyndale University. He writes short stories, poetry, and essays on Medium. He lives in Stouffville, Ontario.