Games of 2014 (1/15)

The Banner Saga, Actual Sunlight, This War of Mine, A Bird Story, and Always Sometimes Monsters kick off our look back at 2014.

The Banner Saga

The best parts of The Banner Saga are not so much played as endured.

Fantasy RPGs are almost always about triumph, about growing more powerful in the face of overwhelming odds, and finally annihilating whatever world-ending force is unfortunate enough to oppose you. Sure, they may take dark turns on the way, but in the end, you are a Hero, and very often the Chosen One.

But everything in The Banner Saga, at least so far – it’s only the first in a planned trilogy of games, after all – is about the long, slow march to the grave. Combat is painful and punishing. A character’s health determines his or her ability to harm enemies, such that characters can be severely injured yet forced to linger on, able only to impotently plink at their enemies, until some merciful opponent finally knocks them unconscious. But while the combat is worthwhile, if a bit repetitive, it’s not the most interesting part of the game.

The Banner Saga is really about the protracted marches from place to place in the cold and frozen wastes. Your caravan steadily eats through your meager supplies, and there is nothing you can do about it. You cannot stop and hunt for food whenever you like, you can only grit your teeth and watch as morale drops and your supplies dwindle, hoping that you will reach the next settlement before too many of your followers starve to death. Sometimes, that settlement does not have any food to sell you.

The Banner Saga is not about being a Hero. It’s about endurance in the face of the end of the world: sad and grim and stubborn and wonderful. It’s about the quiet, futile bravery that forces you to trudge through the snow, ever onwards, though you suspect it won’t make any difference.

Bill Coberly is a law student and occasional writer-of-things based in Minneapolis, MN, where he lives with his wife and two small and snuggly terriers: Azathoth and Nyarlathotep. He is the founder and Editor Emeritus of The Ontological Geek, a website dedicated to games-criticism and geek-culture commentary.

Actual Sunlight

It’s almost impossible to think of Actual Sunlight without comparing it to Depression Quest. Both talk about depression in the most direct, raw and honest sense. Also, both were released in 2013, with a re-release on Steam in 2014 bringing them to a wider audience.

Actual Sunlight, though, is definitely the less interactive of the two: it’s an autobiography of sorts, a “slice of life” in which identification comes through empathy, not choice. It’s also less hopeful. It doesn’t offer any sort of respite, and the protagonist simply cannot be saved. It’s quite painful to play through, but that shouldn’t be seen as a fault. Rather, it’s the result of some powerful writing.

Whether people suffering from depression should play it probably varies depending on the individual. Personally, I saw myself in most of the writing, and I found the experience cathartic. Then I played it again, with my best friend by my side, in order to tell her something about me, through the game’s words rather than my own. That’s how close to home it hit.

In a way, Actual Sunlight didn’t need to be a game. Its linear plot is mostly delivered through text and may very well be delivered an illustrated short story. At the same time, it’s important that it is a game, and it’s important that it is on Steam, for it’s among gamers, like the protagonist, that it will most easily find its audience. Games, with their promise of escapism, attract depressed individuals more than any other medium. Hopefully some of them will stumble upon Actual Sunlight and they’ll find it as cathartic as I did.

Melody is passionate about games, words and music, and she expresses her love by meowing. You can find her on her blog, and on Twitter.

This War of Mine

It’s disquieting, uncomfortable, unnerving. The hellscape that surrounds war manages to creep into the very crevices of life. It’s not just soldiers and combatants who face the horrors of war, but also the civilians caught in the middle. Things like infrastructure, running water, and power are often the first things that go by the wayside when civilization fades into the chaos of combat. In times like these, looters and bandits are the first to emerge from the woodwork, and the non-combatants are usually the first to suffer.

This War of Mine manages to sum up the worst of the volatility, the worst of humanity, and describe just how powerfully haunting it can be to be in those shoes for even an hour, much less a month. It’s a game that gives little respite from how much darkness is out there, and offers little more than a bit of perspective in return. It’s a hard game to play, but a pivotal one; one that gives a bit of insight into just what humanity is made up of, not just what it hopes to be.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer by hobby, grasping at the edges of professional work. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter and his blog.

A Bird Story

It’s tough being a kid with absent parents. Your days are spent in the routine of school and homework, other kids walk right by and through you as if you weren’t even there, and a bird comes to be your only friend. Through a rich environmental narrative, Freebird Games’ A Bird Story tells this tale of friendship without a line of dialogue.

Children can be hard to explain and understand. Sometimes the only word that can explain their crazy antics and foolish stubbornness is “childish”. However, I was rather impressed with how well A Bird Story not only portrayed, but also developed a child character, without a single word mind. Each little clue in the environment was a small treasure that pointed towards more of the storyline and the characters’ lives. The player could understand that the pile of letters on the desk were apologies from the character’s parents and that the character was no longer phased by their absence and saw it as normal.

To remind us of our childhood imagination and the loneliness of lacking friends, A Bird Story creates a likeable character whose endeavours the audience cheers on. While a good chunk of the storyline is unrealistic, it’s easy to see how real it must feel for the character, to enjoy the opportunity to see a child’s dreams come true.

We often speak about and critique narratives in videogames, making remarks on mechanics and character development, but might forget small indie games that achieve beautiful narratives despite their restraint, especially if they release as quietly as A Bird Story did.

Mahreen Fatima is a creative person, game designer, writer, and musician. She started with a viola, which spiraled out of control, leading to a three-car pileup of playing instruments, painting digitally, and writing opinions. Her words can be found on Twitter.

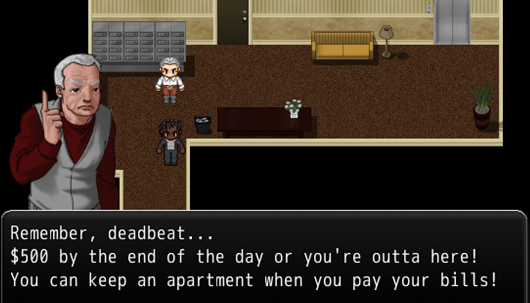

Always Sometimes Monsters

When I first finished Always Sometimes Monsters, I realized that, at last, videogames have found its Clerks. Crude, bawdy, youthful, proudly low-budget and clearly reaching for the stars: the parallels just kept coming. “At least you tried” probably isn’t something you want to hear at an awards ceremony, but Always Sometimes Monsters had me hooked, for a while. It systematized poverty, it compelled me to empathize with a lazy, self-centred protagonist and prodded me with my own laziness, self-centredness and guilt about all of the above.

And yet, in the end the player is left with a cynical, dog-eat-dog world view where two justifiably angry people have to confront one another. One gets the idealized lover and the dream-job and the other gets death and anonymity. In the original ending of Clerks, after Dante gives his “shit or get off the pot” speech, an unnamed mugger busts into the store, shoots him, and leaves.

Hey, it’s black and white and arty. So there’s that.

It feels disingenuous to give credit to Always Sometimes Monsters credit for what it almost is, but in a game framed as a faceless vagrant rambling on about a failed author to a disinterested audience, maybe it fits.

Hey, it’s meta. So there’s that.

Early on the player’s best friend, an addict, is abandoned by a for-profit health-care system, which leaves the player to waver helplessly between saving their friend’s life or drop another rent payment. Then there’s a furry joke and it all works out. Harsh moments are mitigated by cheap jokes and introspection is marred by forced, meaningless, scare quotes “Meaningful Choices.”

And yet, after all that, I still have a soft spot in my heart for Always Sometimes Monsters because, between every step back is a tentative step forward. It wants to explore gender and sex discrimination, it wants to force hapless creative-types to evaluate their priorities. Maybe the shoestring budget and the ersatz design are prodding at my Real Art Response System but even when it let me down I found myself rooting for Always Sometimes Monsters. It might not be enough to sway anyone, but I hope it stands as a warning against risks half-ventured.

Mark Filipowich is the co-coordinator of the Blogs of the Round Table feature at Critical Distance and the curator for Good Games Writing. His worked has appeared in PopMatters, The Border House, The Ontological Geek and many other fine virtual games locales. He has a sweet blog called bigtallwords and he tweets irregularly and irreverently at @MarkFilipowich.