Racing Line: The Bling Era

Miguel Penabella ups every rim size to 24”.

During the reign of Need for Speed in the arcade racing game market in the early to mid-2000s, Midnight Club challenged its rival on numerous fronts. Its open-world design deviates from circuit-based and point-to-point courses, and its frantic gameplay demands twitchy, lightning-fast reflexes to thread delicate cars through traffic and around obstacles at every turn. Seemingly weightless, Midnight Club’s cars drive like remote control toys zipping around, flying through the air, and propping up on two wheels at the push of a button. Midnight Club 3: DUB Edition in particular offers no pretense of realistic automotive racing, but instead presents car culture as exaggerated flash and fantasy aesthetic. Critics during the release of the game in 2005 had a difficult time unpacking its unique approach to the genre. In an old review for The AV Club, the reviewer labels the game as a must-play for “the urban gaming set,” and this clumsy language speaks of a larger critical shortcoming in discussing Midnight Club 3’s tangled relationship with Black artists, hip-hop music, and videogame culture. The game represents a time capsule of a very particular set of cultures and values not expressed in other racing games of its era, marking Midnight Club 3 as a singular artifact of its time.

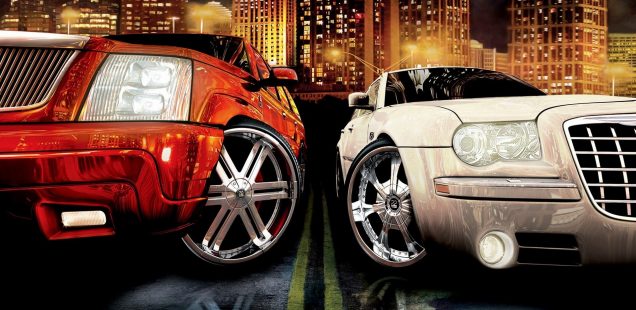

Midnight Club 3: DUB Edition is a game that exists at the intersection of racing games and hip-hop culture in the mid-2000s, an aesthetic immediately made apparent with cover art that spotlights a Cadillac Escalade and a Chrysler 300C, big hefty vehicles with huge rims and low-profile tires that typically aren’t associated with automotive racing. Unlike other big franchises like Gran Turismo or Need for Speed, which draw from Japanese import tuner cultures and European grand touring racing series, Midnight Club 3 invokes the iconography of Black artists: rappers, car customizers, music video directors, etc., particularly from the American South. The prolific music videos produced by Southern rappers during this time—by Mannie Fresh, Dem Franchize Boyz, Nelly, and Mike Jones, for example—directly inform Midnight Club 3’s approach to car culture, privileging muscle cars, luxury SUVs, oversized rims, candy paint, and woodgrain detailing. These artists provide specific instructions on how to decorate one’s car, as when Mannie Fresh raps, “Like that buy that, 24’s [24-inch rims] ride that” or in the Dem Franchize Boyz lyric, “They only riding on 20’s [20-inch rims], they might as well ride on hubs.” By depicting rap artists performing alongside Chryslers, Dodges, and Buicks, these music videos present a view of car culture distinct from the elsewhere sheen of Ferraris and Lamborghinis.

This aesthetic largely stems from Midnight Club 3’s titular partnership with DUB Magazine, a publication that celebrates hip-hop music and car customization. Its covers typically feature the very rappers that soundtrack this game, posed alongside expensive cars equipped with custom DUB wheels, referring to those that are twenty inches or larger in size. The pages of this magazine and the music videos of the rappers who grace its covers help to establish a visual language for the game. In the September 2004 cover issue of Game Informer, a profile of the game and of DUB Magazine creative director Haythem Haddad suggests that the partnership allows the magazine to have active involvement in the game’s production rather than mere window dressing. The article asserts, “You’ll even be able to tint in more vibrant colors, something DUB’s Haddad informed us was one of the newest fashions on the street,” reflecting the magazine’s involvement in aligning the car selection and customization options to the tastes of hip-hop. Staples of hip-hop car culture such as classic Oldsmobile and Buick sedans appear as playable vehicles, which contemporaneous games like Need for Speed overlook in favor of high-end foreign engineering. These American cars serve as the canvas for the lowriders esteemed in West Coast hip-hop, the slabs of Houston rappers, and hi-riser donks of Atlanta and the South. Customization options emphasize aesthetic details of hip-hop, including one of the largest selections of licensed rims in any racing game at the time. These hip-hop-inflected car and customization options enable players to replicate the style of music videos like in Rich Boy’s “Throw Some D’s” video, in which a parade of Cadillac sedans with giant Dayton rims encircle the rapper as he performs, or in a variety of T.I. clips where “rims sit high” and you pull up “sitting on 20 somethings.”

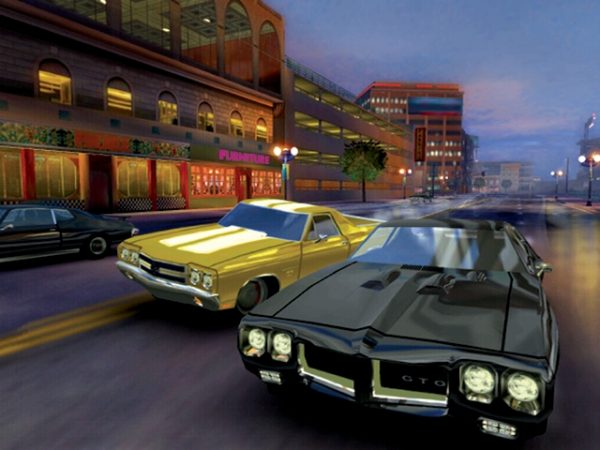

Midnight Club 3 deviates from its closest arcade racer rival, the Need for Speed series, in its total embracement of hip-hop car culture. In the aforementioned Game Informer issue, Haddad takes direct aim at the rival series, contending, “Need for Speed: Underground is a fun game. But, there are a lot of aspects of the game aesthetically that have no bearing on our market. It doesn’t hit on the characteristics of the cars. It’s not very current, either. A lot of the trends you see in there are kind of passé now. They were a little more popular three or four years ago.” Underground almost exclusively features Japanese tuner imports, riding on the zeitgeist of the Fast and the Furious movies of the early 2000s. While its sequel introduced a few SUVs like the Cadillac Escalade, these other types of vehicles are not deeply woven into the visual language of hip-hop like in Midnight Club 3, which also expands vehicle options to luxury sedans, trucks, muscle cars, choppers, etc. The distaste for Japanese tuner cars during this era of hip-hop music can best be summarized in a moment in the “King Kong” music video by Jibbs. Here, the rapper idles in a black muscle car as an orange import tuner pulls up and taunts him, directly referencing the climactic final race of The Fast and the Furious. But before a race can begin, the muscle car’s powerful subwoofers incapacitate the import challenger. Midnight Club 3 imagines a similar world that decenters the primacy of exotic cars and import tuners. One of the first racers encountered in the game is Bishop, who drives a… Lexus. His crew also includes a Dodge Magnum, a hulking station wagon outfitted with giant rims and a metallic paint job. The game constantly pits the player against the kinds of vehicles featured in rap music videos or on DUB Magazine covers, depicting a world where Chevy Impalas can outrun even high-performance supercars.

In this broader cultural context of DUB Magazine and rap music videos, I consider Midnight Club 3: DUB Edition a prime example of videogames in the midst of its own “bling era,” coinciding with rap music’s so-called bling era of rampant commercialization and flash. This era marks a lucrative partnership between the hip-hop music industry and the videogame industry, with both reaching unprecedented heights in mainstream popularity. This era saw the permeation of hip-hop culture into various corners of videogames. The Def Jam fighting games allow prominent rappers from Ludacris to Busta Rhymes to brawl with members of the Wu-Tang Clan. The pair of 50 Cent games attempt to portray the rapper as a larger-than-life, unkillable figure, suitable for the persona he shapes in his lyrics. Snoop Dogg is an unlockable character with his own mission in True Crime: Streets of LA, and an assortment of franchises like Fight Night, NFL Street, and Need for Speed feature soundtracks with 2000s hip-hop staples Dipset, Terror Squad, Lil Jon, and the Ying Yang Twins. Even The Sims cashed in with the questionable Urbz spin-off, featuring a storyline with the Black Eyed Peas.

Midnight Club 3: DUB Edition is a racing game encoded with hip-hop DNA, and I’d argue that the game draws more from the visual and auditory style of something like NBA Street than Need for Speed, fully committing to the cultural language of hip-hop. Much of its licensed soundtrack comprises hip-hop tracks (in addition to racing game drum and bass standards), but there’s also a collection of unattributed hip-hop instrumentals that accompany race finishes, loading screens, and garage visits. This commitment also extends beyond the text of the game itself, as Midnight Club 3 also boasts a separate promotional mixtape (titled Custom Mix for Your Whip) of songs not licensed for the game, featuring essential mid-2000s rappers like Fat Joe, Twista, Fabolous, and Missy Elliott. In contrast, 2005’s Need for Speed: Most Wanted is a nu metal game, as its soundtrack is largely composed of heavier rock music that complements the game’s rusting, post-industrial cityscapes and desaturated visuals that invoke such bands’ gritty music videos of the time. Earlier games from the Underground series do include iconic uses of rap songs, such as “Get Low” and the “Riders on the Storm” remix with Snoop Dogg, but those games do not wed hip-hop aesthetics with car culture down to the granular level of vehicle selection and customization as Midnight Club 3 does. No other racing game has since.

While videogames enjoyed a synergistic relationship with the hip-hop industry throughout the 2000s, I’d suggest that its bling era ends in 2009 following a pair of key releases: the maximalist masterpiece 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand and DJ Hero, a music game released during the decline of that game genre’s popularity. Larger cultural shifts in hip-hop music at the end of that decade also signaled a change in values, as fresh-faced, alternative-minded rappers like Kid Cudi or (early career) Drake supplanted the flashy, tough-guy braggadocio of old guard artists like 50 Cent. Moreover, hip-hop artists’ tastes in cars also changed, generally shifting towards luxury and high-performance supercars, aligning with rappers’ gradual embracement of high fashion circles. One need only look to some of the big hits in the early 2010s, as when Future raps, “I woke up in a new Bugatti” or when Kanye West and his pals rap about being “in that two-seat Lambo.” Because of this quickly changing cultural landscape, Midnight Club 3 captures a very specific moment in time. In 2005, hip-hop was reaching new commercial peaks. Its ties to car culture could be seen everywhere, from shows like Pimp My Ride to the pages of DUB Magazine, but Midnight Club 3 was its videogame champion.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating the spread of conspiracy online. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.