Opened World: Kentucky Route Zero Act III

Miguel Penabella talks and listens to them talking.

This is part three of a comprehensive overview of Kentucky Route Zero. See also: Part one, part two, part four, and part five.

Throughout Kentucky Route Zero Act III, a legacy of debt weighs heavily on Conway. His injured left leg—treated by a doctor in the previous act—now glows in a skeletal, electrified form, visibly marking him as a debtor who owes medical bills to the predatory Consolidated Power Company.

This accretion of unpaid dues haunts the game’s characters, and through the game’s rich dialogue system, we navigate Conway’s relationship with debt prior to the events of the game as well. Act III finally expands upon the sad, intimated backstory between Conway and his antique shop employer Lysette, her late husband Ira, and her late son Charlie. Dreamy flashbacks relayed through text unspool narrative threads that players must disentangle by working through memories of failing businesses, alcoholism, unrequited romance, and death. Kentucky Route Zero’s dialogue system deemphasizes how choices affect the future, as in Telltale games like The Walking Dead (Clementine will remember that), instead refocusing attention to how choices affect our understanding of the past (Conway remembered that). There are no right or wrong dialogue choices. Rather, Kentucky Route Zero grants players the ability to guide—rather than outright control—the game, allowing us to gently shift the temperament or mood of any given scene, as well as to shape character dispositions and backstories.

This accretion of unpaid dues haunts the game’s characters, and through the game’s rich dialogue system, we navigate Conway’s relationship with debt prior to the events of the game as well. Act III finally expands upon the sad, intimated backstory between Conway and his antique shop employer Lysette, her late husband Ira, and her late son Charlie. Dreamy flashbacks relayed through text unspool narrative threads that players must disentangle by working through memories of failing businesses, alcoholism, unrequited romance, and death. Kentucky Route Zero’s dialogue system deemphasizes how choices affect the future, as in Telltale games like The Walking Dead (Clementine will remember that), instead refocusing attention to how choices affect our understanding of the past (Conway remembered that). There are no right or wrong dialogue choices. Rather, Kentucky Route Zero grants players the ability to guide—rather than outright control—the game, allowing us to gently shift the temperament or mood of any given scene, as well as to shape character dispositions and backstories.

In an interview with scriptwriter Jake Elliott on the dialogue mechanics of the game, Alex Wiltshire differentiates Kentucky Route Zero from other classic adventure games like those of LucasArts, in which dialogue options typically double back on themselves so that players can explore all possible options. And unlike the world-altering choices of BioWare titles, Kentucky Route Zero avoids foreclosing “good” or “bad” endings but is instead interested in revealing the open-ended, interior lives of characters through dialogue choices. In this way, the dialogue of the game is more character-driven than plot-driven. Choices often revolve around a character’s opinion about a place or another person, prompting players to envision the kind of protagonist they want Conway to be. When confronted with a stranger, is Conway on guard or curious? When traveling companion Shannon asks about his past, is Conway reserved or candid? Your choices dictate how much or how little you know about Conway and the other characters, lending the game a different temperament depending on your access to information. While the game lacks immediately discernible narrative consequences with each dialogue option, our choices still have meaning. Each player will shape their own version of Conway with each playthrough—his affect, his behavior, whether or not he’s gentle and introspective or tight-lipped and stoic—and in doing so, you more clearly understand the complexity of his backstory and inner life. Because choices are not heavily weighted with dire narrative consequences that lead to good or bad endings, Kentucky Route Zero’s dialogue remains ambiguous as to how it factors into the game, resulting in a meandering, poetic open-endedness.

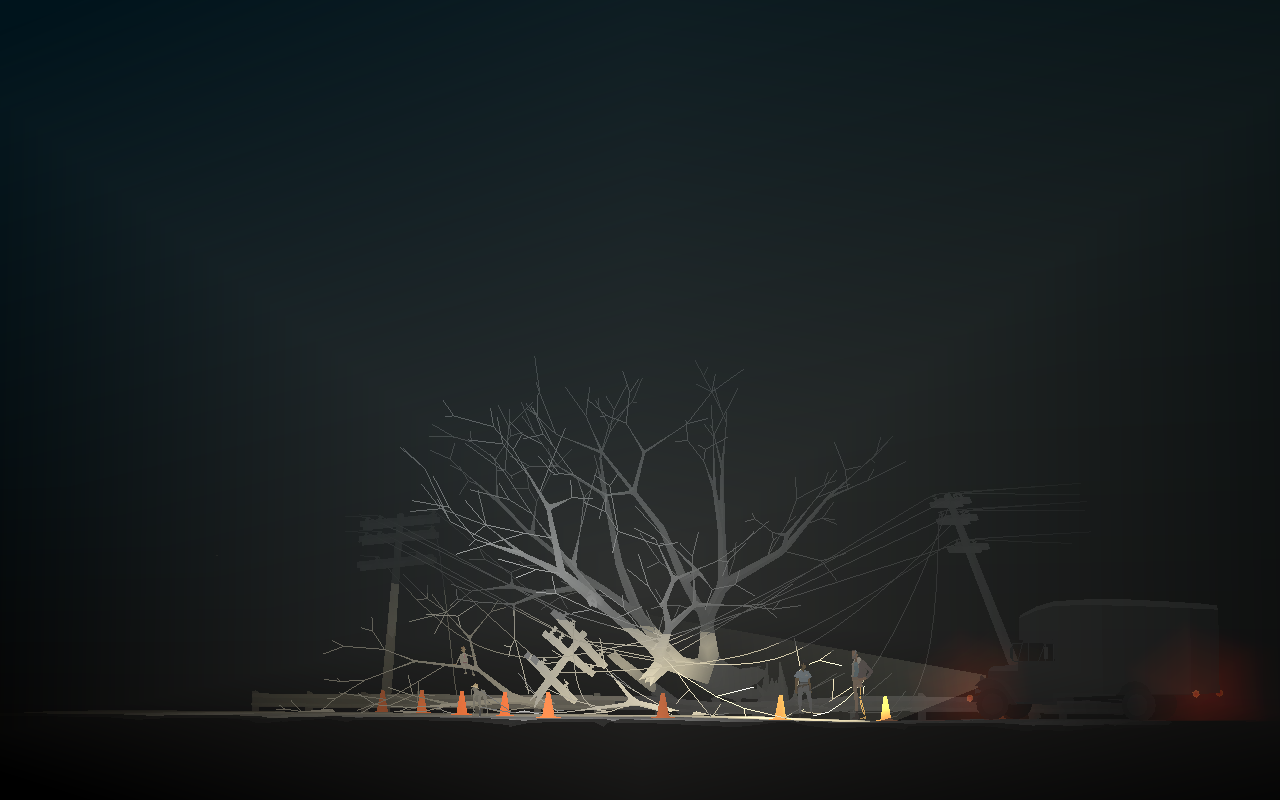

Act III provides a succinct example of how players must interpret the temperament of characters in order to influence the mood of a scene rather than forge far-reaching narrative outcomes. Early in the act, a skeletal tree lies supine across downed telephone wires, with the headlights of a parked vehicle illuminating the inky nighttime dark. Shannon, Ezra, Conway, and his dog idly linger in anticipation for a tow truck to rescue Conway’s stalled vehicle. Shannon calls a tow truck hotline, but players roleplay as the employee on the other end of the line, responding as the unseen character. Dialogue choices are limited to inaudible words inflected by a certain tone of voice. When Shannon inquires about towing services, the game presents three options:

PHONE: (Inaudible, accusatory.)

PHONE: (Inaudible, inquisitive.)

PHONE: (Inaudible, suspicious.)

While Shannon speaks in full sentences, this whole conversation unfolds with players answering in these inflected mumbles. The content of our words is left to inference; our choices shape the tone of the call instead, as players can later respond as wistful, apologetic, maudlin, pragmatic, neighborly, and so on. All choices lead to the same conclusion, but each response prompts introspection on the part of the player, asking us to imagine what feelings are being provoked in this telephone conversation. Indeed, Lindsey Joyce lucidly identifies how the game’s nuanced dialogue trees demand that the player “project your understanding and interpretation onto the narrative itself” rather than simply select binary good or bad choices mapped onto a consequential teleology.

While Shannon speaks in full sentences, this whole conversation unfolds with players answering in these inflected mumbles. The content of our words is left to inference; our choices shape the tone of the call instead, as players can later respond as wistful, apologetic, maudlin, pragmatic, neighborly, and so on. All choices lead to the same conclusion, but each response prompts introspection on the part of the player, asking us to imagine what feelings are being provoked in this telephone conversation. Indeed, Lindsey Joyce lucidly identifies how the game’s nuanced dialogue trees demand that the player “project your understanding and interpretation onto the narrative itself” rather than simply select binary good or bad choices mapped onto a consequential teleology.

As we are unfamiliar with Conway’s history prior to the events of the game, dialogue choices also prompt us to shape his memory of the past. Kentucky Route Zero’s dialogue is disinterested in binary moral dilemmas and clear causality, instead serving as a means to provide richer context to characters and develop their backstory. Following one route in a dialogue tree can potentially open up a past mental burden that may come to define the character, or perhaps not. This backstory is dependent upon the player choosing whether or not to open up these old wounds or skirt around the subject to discover new paths of character development. In a hazy flashback, our intervention in dialogue suggests that Conway has difficulty remembering the past clearly and thus requires our help. Conway invokes a memory of Lysette speaking to him: “We were up on a roof. Ira and I, and Charlie. Eating a light supper. I was drinking sweet tea. Charlie was reading. We were surrounded by other houses, closely packed. Huge sidewalks, it must have been a … what’s that word …”

CONWAY: A city.

CONWAY: A subdivision.

Regardless of which response is chosen, Lysette accepts Conway’s words and continues her rumination; your selection does not affect her reaction. But in the back of our minds, the backstory has changed. Framing the characters as either city or suburban dwellers greatly inflects the tone of the conversation, and players will come to imagine Conway differently as they fill in the details of his backstory, even as the overall narrative remains the same. When Lysette eventually calls upon the memory of her late son Charlie, we have the option to select Conway’s perception of his death. Lysette implores him to recognize that “It wasn’t anyone’s fault, Conway. That’s what we mean when we say it’s…”

CONWAY: An accident.

CONWAY: A tragedy.

CONWAY: A shame.

Lysette responds with the single word, “Sure,” its brevity overdetermined with meaning depending on your dialogue choice as Conway. Even though she replies the same way no matter which choice is made, we alter the tone of the conversation and the inflection in her response. The lack of voice acting in the game means that there’s no fixity to how the word “Sure” is meant to be articulated. If Conway views Charlie’s death as an accident, then “Sure” might come across as Lysette still unconvinced in his interpretation of events. If he thinks it to be a tragedy, then “Sure” might suggest that Lysette’s still grappling with her grief and is unsure what to say. If Conway admits that Charlie’s death was a shame, then “Sure” might simply be a word that’s better than silence, because maybe they both feel somehow complicit and ashamed at having failed to prevent his passing. This indeterminacy suggests how any response will always be inadequate to address the weight of personal loss. Conway’s replies simply give voice to his own (and thus, our) interpretation of events at that given moment in time.

These flashbacks to conversations with Lysette reveal that Conway continues to harbor guilt over Charlie’s death. His delivery of a package to 5 Dogwood Drive—the framing device and Conway’s ostensible main objective that motivates his travels throughout the game—serves as the fulfillment of a final debt to Lysette. This obligation is as a way for him to maintain one final, tenuous connection with her, binding the two characters together. Perhaps the roundabout journey that Conway takes through Kentucky Route Zero, endlessly prolonging the arrival to what should be a simple destination, suggests an inability to move on from Lysette, as completing his job would mean that she has no use for him anymore. As Gavin Craig suggests in his review of Act III, indebtedness to others has the function of “staving off resolution,” and may serve as “stable points of reference” in a precarious world of ephemeral moments and spectral characters. The flashbacks to Conway’s relationship with Lysette reveal the pain of his past life, and his journey represents a wayward retreat from his problems, along with other characters similarly fleeing from personal and economic hardship.

Ultimately, Act III invokes the sublime in its dialogue choices, suggesting how artistic performance can potentially mitigate—or even transcend—this sorrow. Much has been written about the rousing musical centerpiece of Act III, and Ansh Patel’s astute article proposes that such moments compel players to consider how to best contextualize character temperaments within your particular experience of playing the game. Shannon, Ezra, Conway, and his dog befriend the bohemian vagabonds Junebug and Johnny, following the pair to The Lower Depths bar for an after hours musical performance. Taking the stage to a small, intimate audience, Junebug and Johnny’s rendition of “Too Late to Love You” embraces the cosmic. As composer Ben Babbitt’s airy synths and bossa nova drum leitmotif from “Nameless Interiors” initiates the song, the ceiling slowly levitates and disappears, opening the dingy space to a majestic, starlit night sky. Junebug magnetizes us with her swaying, graceful presence, mysteriously transforming into a Loretta Lynn-like figure dressed in a vibrant blue gown. The full moon dances above, a comet shoots through the sky, and the stars twinkle like heavenly stage lights. When the first verse arrives, players are greeted with a choice of opening lyrics, prompting us to partake in songwriting:

Ultimately, Act III invokes the sublime in its dialogue choices, suggesting how artistic performance can potentially mitigate—or even transcend—this sorrow. Much has been written about the rousing musical centerpiece of Act III, and Ansh Patel’s astute article proposes that such moments compel players to consider how to best contextualize character temperaments within your particular experience of playing the game. Shannon, Ezra, Conway, and his dog befriend the bohemian vagabonds Junebug and Johnny, following the pair to The Lower Depths bar for an after hours musical performance. Taking the stage to a small, intimate audience, Junebug and Johnny’s rendition of “Too Late to Love You” embraces the cosmic. As composer Ben Babbitt’s airy synths and bossa nova drum leitmotif from “Nameless Interiors” initiates the song, the ceiling slowly levitates and disappears, opening the dingy space to a majestic, starlit night sky. Junebug magnetizes us with her swaying, graceful presence, mysteriously transforming into a Loretta Lynn-like figure dressed in a vibrant blue gown. The full moon dances above, a comet shoots through the sky, and the stars twinkle like heavenly stage lights. When the first verse arrives, players are greeted with a choice of opening lyrics, prompting us to partake in songwriting:

When you left me …

I never should have met you …

I wish we’d met before …

Upon selection, Junebug sings a unique verse based on the lyrics chosen. Quiet, melancholy verses recount the unrequited heartache of a missed connection before erupting in a haunting outburst of synthesized reverb during the chorus. Junebug’s achingly beautiful, otherworldly voice envelops the space, underscoring the sadness of the song. Patel compares the scene to the opera sequence of Final Fantasy VI, in which dialogue choices similarly cue players to choose lyrics to a song. Unlike that sequence, however, Kentucky Route Zero eschews distinguishing between right and wrong answers. Rather, the lyrical choices of “Too Late to Love You” suggest another moment of introspection. Which lyric best appeals to your emotions at this moment in time? How should Junebug best express a sense of intimate longing and dejection?

The hurt you left behind …

I never thought I’d miss you …

As long as you were gone …

These choices recall Conway’s inputting of lines of poetry for a computer password in Act I, in which players must shape the poetic flow and mood of a stanza. Here, each selection produces a four or five-line verse and chorus, but it all leads to the same dialogue tree upon the next round. Like the dialogue choices that shape conversations throughout the game, we encounter certain inevitabilities. Regardless of the choices made, each one ends with identical lyrics: “you waited too long, darlin’, it’s too late. It’s too late.” While the chorus will always remain the same and the basic structure of the song unchanged, our experience and understanding of the emotions being conveyed will be different. Depending on the opening lines of verse chosen, the narrator of the song may come across as hurt, or regretful, or yearning, or disconsolate.

I thought that somehow love would find a way …

I thought that somehow love would find a way …

There were months I wished you’d come back every day …

After years I know that I’m bound to my fate …

Junebug recalls having heard this song from an open mic night long ago, and players aid in her reconstruction of half-forgotten lyrics and emotions. As she digs into the past, the lyrics invoke Lysette and Conway’s own unrequited love, interrupted by the former’s marriage to Ira and the latter’s lonesome alcoholism. The foreclosure of Lysette’s antique shop means the foreclosure of their relationship, and Conway’s final delivery serves as a perverse form of existential security that conscripts him to her. In Kentucky Route Zero, debt is always inscribed in characters, their relationships, and even their bodies. It deteriorates and binds people, trussing them to the burden of labor. But in a downstairs bar, in a moment of pause, Junebug’s song transcends it all, lifting us away from the weight of economic woes and personal failures, untethering us from the ground.

In future installments of this comprehensive overview of Kentucky Route Zero, I’ll share some ruminations on floating, forgetting, and the free-flowing passage of slow time.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.