Opened World: In Ecstasy of Images

Miguel Penabella holds an intervention.

When we think about drug culture in media, we can call to mind several distinct styles. Stoner movies conjure up the soft focus marijuana haze and warm West Coast sunniness of comedies like Pineapple Express or Cheech & Chong’s Up in Smoke. The seminal films about tripping on LSD emphasize colorful and outlandish imagery like The Holy Mountain, and modern LSD films like Enter the Void often visually pulsate with nightclub energy. The druggy style can also be bleak and depressing, as in the lo-fi heroin grunge of movies like The Panic in Needle Park or the recent Heaven Knows What, two films that transform New York City into a grimy hellhole with images so immediate you can practically smell the squalor and feel the winter cold.

And what about drug culture and videogames? Is there a proper stoner videogame? Have games engaged with the visual styling of drug culture in any meaningful way? A number of games exhibit silly, absurdist humor that may be accentuated while baked, such as I Am Bread or Katamari Damacy, but this isn’t the same thing as direct engagement with the stylistic context of drug culture. When drug use is portrayed directly or even narrativized, games often fall into juvenility and sidestep the potential for sustained thematic engagement with drugs. Grand Theft Auto V includes a brief scene of freefalling after a character is anesthetized with a vague concoction, and characters can embody animals like hawks or rabbits in hallucinatory out-of-body trips after consuming peyote. The game makes novel attempts to portray a drug-induced state, but Grand Theft Auto V ultimately relegates such moments to comic relief rather than committing to any serious thematic engagement.

Videogames often find ways to turn drugs into systems. Drugs become merely power-ups that unlock abilities like slowing down time or boosting attack stats, quantifying and flattening a feverish, wild trip. The abstract, druggy condition of intoxication instead becomes something that can be controlled and monitored by the player. Only a few games effectively engage with drug culture, such as LSD: Dream Emulator, a game that allegorizes the delirium of the titular drug with the whimsicality of dreaming. If videogames want to create a trippy, drug-like experience, then visual style ought to be taken into greater consideration to evoke the feeling of getting high or hallucinating rather than portray drugs as controllable systems.

One overlooked series in relation to drug culture, despite its evocative style, is the Wipeout series by developer Psygnosis. The Wipeout games—and in particular Wipeout 3, the high point of the franchise with its original art by The Designers Republic studio prior to their departure from subsequent games—engage with drugs allegorically in their lush visual style and relationship to electronic music and the broader 1990s rave culture in the United Kingdom. In short, the Wipeout games are ecstasy games. The series’ stylized title as printed on the box art, wipE’out”, is commonly believed to allude to the slang “E” of ecstasy. Indeed, in the insightful retrospective of Psygnosis by Eurogamer, Psygnosis artist Neil Thompson acknowledges the interpretation that the title refers to ecstasy as “absolutely intentional, obviously.” Conversely, Wipeout developer Nick Burcombe leaves it ambiguous, countering that “It was just the way that font had been designed” and that the drug reference “was not my understanding of it at all.”

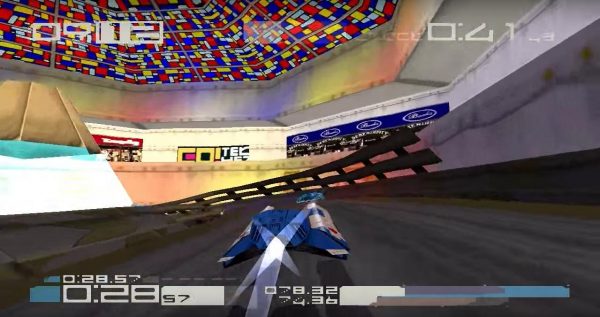

As one of the most popular drugs of dance music and 1990s rave culture, methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, AKA Ecstasy) produces a stimulating state of euphoria heightened by the energetic displays of flashing light and color at rave parties, particularly by the prevalence of glow-in-the-dark neon fashion and glow sticks. In Wipeout, the streak of light pouring out the back of an anti-gravity ship and the colorful speed-boost pads generously peppered around tracks like a pulsating dance floor reinforces the series’ mimicking of ecstasy visual culture and the associated rave scene of the period. This connection is perhaps best exemplified in the Mega Mall track of Wipeout 3, with its profusion of televisual screens and strange advertisements that look like decorations for nightclubs. At one point, the track dramatically spirals downward under a kaleidoscopic ceiling of neon colors. Lights pulsate and glow, and the constant blast of techno and trance music calls to mind the experience of clubbing.

In fact, Wipeout was literally born to the world in a nightclub, originally seen as a crude pre-rendered prototype played by Angelina Jolie in a club for the movie Hackers in 1995. Although racing games are typically designed to have innocuous content appropriate for all ages, the Wipeout series connects with the experience and aesthetic of drugs in proxy. For instance, its strategy closely mirrors the cartoon series Samurai Jack’s use of coded imagery in a sequence of hypnotized bodies set to electronic rave music (complete with druggy pacifier). In the more polished, snaky racetracks of Wipeout 2097 (otherwise known as Wipeout XL) and Wipeout 3, the combination of the pulsating lights and the repetitive movements of racing produce a trance, especially when plunged into the cavernous neon voids of 2097. The sheer speed of the anti-gravity vehicles coerce players to rely on intuition and feel, surrendering careful strategy in favor of simply letting go. This sense of relinquishing control is augmented by the propulsive, spellbinding licensed soundtrack featuring iconic 1990s electronic acts like The Future Sound of London, Orbital, The Chemical Brothers, and Underworld. What the Wipeout games resemble is a distillation of the energy and woozy visuals while high on ecstasy at a rave, engaging with the imagery of drug culture even if it never addresses it directly.

The closest that Wipeout has gotten to acknowledging its position as a stoner game comes in the form of the original game’s infamous promotional poster. The advertisement visualizes an implied drug overdose with noted Radio 1 DJ Sara Cox bleeding from her nose and eyes wide open in a daze. The poster shows no obvious sign that it’s marketing a videogame besides the PlayStation logo, ESRB rating, and the tagline “a dangerous game.” Indeed, the imagery seems fitting for a landmark drug movie like Trainspotting or a public service announcement about the dangers of illicit drug use. Even one of the attached review blurbs evokes the language of drug culture: Wipeout “will leave you drenched in sweat and grinning.” The remark also invokes ecstasy’s sexual dimension, and although the Wipeout games lack any obvious sexual content, the gameplay’s tactility and emphasis on feeling the layout of the track connotes a level of coded sensuality.

Wipeout’s articulacy in the aesthetic of 1990s drug and nightclub culture is due largely in part to the prodigious art design and marketing by The Designers Republic, headed by Ian Anderson and staffed with artists like Keith Hopwood and Lee Carus. Known primarily for creating album art for electronic musicians (especially on the renowned Warp Records label) like Aphex Twin and Autechre. In Wipeout, The Designers Republic utilized subversive, pop art iconography poking fun at corporate branding. These games’ colorful advertisements for fictional corporate goliaths and extravagant racing leagues comprise a psychedelic future replete with visual stimuli. Dizzying light shows and a parade of eccentric logos vie for attention while racing, and speeding by them blends such blurry images into one intoxicating rush.

One of the most visually striking sequences concocted by The Designers Republic is the opening credits sequence (beginning at 0:54) from Wipeout 3. Without context, we’re greeted with an enigmatic and overwhelming flurry of words and pictures. The sequence is comparable to the opening credits of the aforementioned Gaspar Noé movie Enter the Void. By presenting audiences with a quick succession of stylized typography and fictional Nihon-pop branding, both sequences suggest a druggy fever dream of half-remembered stimuli. A drug-induced state warps familiar images into something fleeting and aggressive, and those playing the Wipeout games enter a similar kind of hallucinatory trip.

The rich aesthetic of these games immerses players into an illusory world inspired by raves, ecstasy, and futurist styling, but it also resembles a darker dystopia. If we are to consider the Wipeout series as stoner games, then we must also consider the drug-induced paranoia and countercultural politics that often coincide with drug culture works everywhere from Philip K. Dick’s drug dystopia in A Scanner Darkly to the cannabis-flavored, post-Watergate conspiracies in Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice. In Wipeout, omnipresent advertisements cynically trumpet corporatism’s chokehold on a crowded society, and the glitzy images blur our vision of reality like a kind of somatic drug. This future world of druggy images evokes Darran Anderson’s observations for Versions on Blade Runner and cyberpunk, noting how “The colossal, recurring geisha girl on the electronic billboard is significant not for what she is advertising (the pill, as it happens) or even the echo of the decadent ‘Floating World’ of Tokyo legend but for the implication that the future is both otherworldly and compromised.” Similarly, the billboards and screens scattered around Wipeout’s racetracks not only serve to hide the limited draw distance of the game but also the environmental degradation and Malthusian over-crowdedness of the fictional world.

In the Wipeout games, grandiose corporations obsess over lethal spectacle and dress up the vehicular carnage with pretty lights and colors to make it seem palatable. Racing in Wipeout is corporate-sanctioned bloodsport, rendered palatable by a rush of intoxicating stimuli. When a certain reality proves depressing, the trip is more pleasurable, but we must eventually come crashing back down. In emphasizing the thematic tensions and trippy aesthetic of ecstasy, rave culture, and electronic music, the Wipeout series epitomizes what a stoner or drug videogame can look and feel like. The ubiquitous colored lights and flashing screens are too insistent to be mere embellishment; they’re the rave we’re invited to and the implied high by which we are transported to an ecstatic, nocturnal party in whose midst we go faster and even higher.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.