Let’s Play a Love Game: ‘Slow Damage’ and the Artist’s Palette

Eric Cline considers the tools of creation.

Disclaimer: JAST USA provided a review copy of this title. Spoiler-wise this essay discusses key plot details and reveals from the final/Fujieda Ryo route.

Last month I wrote about my first impressions of Nitro+chiral’s latest release, Slow Damage. Specifically, I discussed how the game’s nuanced handling of violent themes colored my understanding of the characters and their circumstances in the cyberpunk locale of Shinkomi. Now that I’ve had time to finish the game, I’m turning my attention to the game’s theme of artistic creation and how that theme is reflected by unique decisions in gameplay design.

Slow Damage largely follows basic tenets of visual novel gameplay; the player reads through events in a predetermined order and affects the story’s progression primarily through occasional choices made at branching points. These aren’t the only opportunities the developers have provided for players to provide direct input, however. Slow Damage is differentiated from past N+c titles by its incorporation of unique ‘Exploration’ and ‘Interrogation’ modes.

During ‘Exploration’ phases the player is able to choose various spots within Shinkomi to visit, from protagonist Towa’s atelier, to his favorite bar Roost, to the Murase Clinic at which he works. In most cases visiting a location will result in Towa coming across another character whom he can interact with in simplified versions of what the game terms ‘Interrogations’. In these discussions Towa is able to choose between explicitly labeled Positive (generally assertive) or Negative (generally passive) responses, which influence the other characters’ reactions in turn.

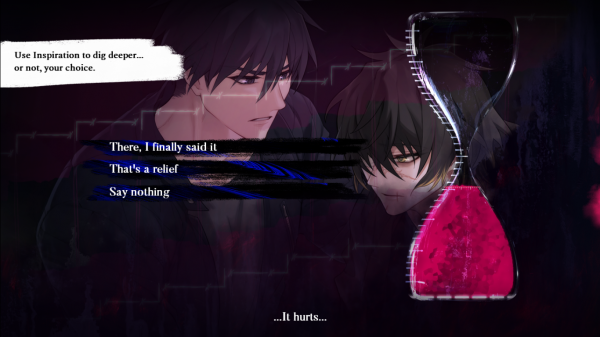

Longer, more plot-critical Interrogations occur at branching points throughout Slow Damage, usually toward the ends of chapters. Towa will engage in one-on-one conversations in which his goal is to draw plot-critical information from other characters. There’s an element of verbal sparring here; careful consideration of one’s responses is essential to success. The confronted characters’ reactions are measured via Euphoria and Madness levels; these essentially gauge whether Towa has successfully influenced others to let their walls down. Euphoric resolutions to Interrogations are requisite to continuing the story proper whereas raising the Madness meter too high has the opposite effect: the game comes to a premature conclusion through a ‘bad end,’ often defined by traumatic events.

Avoiding bad ends is contingent on successful use of another gameplay mechanic: the ‘Palette.’ During the Exploration phases’ shorter conversations, certain words and phrases stick out to Towa. The Palette is a collection of these remembered phrases which Towa can later choose between at critical points during Interrogations. In this way Towa’s past experiences provide direct inspiration for future interactions as he strives to build intimate connections with others.

This metaphorical use of a palette to convey Towa’s memories of past conversations (and the player’s resultant Interrogation choices) is a natural one given Towa’s interests as an artist himself. Towa takes inspiration from helping others fulfill their deepest desires, particularly when said desires are socially taboo. For him, an art model is not someone to paint a portrait of, but rather someone to partner with in what he calls Euphoric episodes: intimate encounters that often involve intense acts of violence or stimulation, but not necessarily actual sex acts. Many of the game’s longer Interrogation sequences occur during these episodes as Towa seeks to help his models/partners achieve a sort of emotional climax.

The Palette mechanic seems to be a way for players to join in on Towa’s creative process. Just as he reflects on past encounters in his efforts to deepen his connections with other characters, so too must the player reflect on these interactions in order to progress the plot. What one gains from a story is intrinsically tied to what one brings to it, whether that be one’s artistic biases, hopes and expectations, or even emotional baggage and personal philosophies. From this lens the mere act of engagement endows the player with a sort of co-creator status, and Slow Damage isn’t content to leave such a relationship theoretical. Rather, it actively invites the player to ponder these concepts by framing gameplay options through the tools of Towa’s own artistic trade.

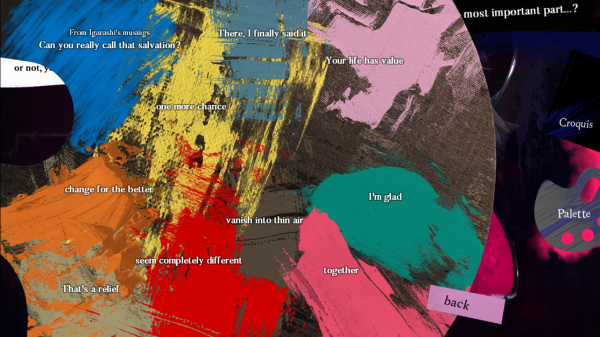

Presentation-wise, the Palette itself is evocative. Upon clicking on the Palette icon on the screen’s right side, one is treated to a close-up featuring all the phrasal inspiration the player has collected thus far, each represented by a different hue of paint on a literal palette. Beyond the image’s sheer aesthetic appeal, it also emphasizes the human emotion that goes into Towa’s inspiration gathering. Hovering over phrases results in additional text appearing to remind the player of where said phrase originated such as “from Igarashi’s musings.” The acquisition of phrases is also striking, as paint splatter streaks across the screen each time new inspiration is found.

Unfortunately, the actual experience of drawing upon these inspirations in-game is less euphoric. This is largely due to the tension that naturally arises from trying to imbue a sense of choice within a game genre that is largely defined by constraint. Visual novels are, to a large degree, text-based stories that elevate their language with art and music. Even with branching paths and multiple endings, the player can never pursue a story the developers haven’t written. This, coupled with the relative strictness with which players must make correct decisions lest they get a premature ending, hinders the ability of the player to feel like an active participant in the art-making process and not just an observer.

In the game’s defense, it sometimes utilizes the Palette concept’s inborn constraints in such a way as to elevate the story’s themes and poignancy. In the final route, Towa works alongside love interest Fujieda to discover the truth behind his long forgotten past. After returning to a site of childhood trauma, Towa is bombarded with memories and realizations about what happened there, not just to him but also to his old friend, Fujieda’s younger sister. In his shock at remembering the truth Towa grows weak and faints, later to be found by a worried Fujieda who tries to get Towa to tell him what he’s remembered.

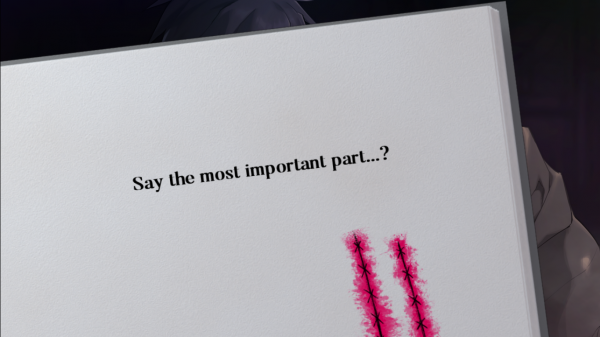

Their exchange takes place within the context of an Interrogation, and one with the least margin of error of any in the game. The player can’t make a single deviation from the correct choices without getting a premature Madness ending. The correct course of action? To opt not to use any of the phrases available on one’s palette, and to remain silent every time Towa is prompted to speak.

While the concept of taking inspiration from past interactions in making decisions is a cool one, it’s not the appropriate course of action here. Faced with the horror of the abuse he’d long locked away from his conscious mind, Towa can’t find refuge in the words of others. The trauma is his own to contend with. As the player keeps rejecting the opportunity to reuse phrases from the Palette, Towa struggles against his sense of panic to try and tell Fujieda the truth of not just the horrors he faced but of what happened to Fujieda’s sister as well. When the player clears the Interrogation successfully, Towa finds the strength to speak the truth—a truth that those around him, his usual sources of inspiration, never could.

Here the developers manage a very difficult task: not only justifying a restriction of freedom in-game, but using it as a means of thematic reinforcement. Some players might find the relative difficulty of achieving Euphoric ends frustrating; without consulting a guide, it can sometimes be difficult to grasp the proper course of action. In the case of Towa’s Interrogation with Fujieda, however, that extremity of limitation becomes a poignant statement: while Towa regularly draws upon the words of others in creating his art, there comes a time when his own voice is not just the most important, but the only one that matters.

Ultimately, Slow Damage’s utilization of its Interrogation and Palette functions isn’t perfect. The inherent tension between the desired sense of creation and the hard-coded limits for player input are definitely felt. With that said, the concepts this gameplay calls to mind mirror Towa’s status as an artist and often reinforce the story’s poignancy. All good art is flawed, and what Slow Damage endeavors to do between all its cracks is well worth considering.

Eric Cline is a writer, editor, and podcaster. Besides being a columnist for Haywire Magazine he also co-hosts the comic book appreciation podcast Chris and Eric’s Longbox Adventure. His Twitter is @ZorakRichardson.