Let’s Play a Love Game: ‘Slow Damage’ and the Intimacies of Violence

Eric Cline gets close and personal with violence.

Disclaimer: Jast USA provided a review copy of this title. Spoiler-wise, this essay discusses key events from the game’s opening chapter “Fraise” as well as both chapters unique to the Rei route: “Brother” and “Izumi Rei – Contradiction.”

Almost two years after its Japanese release, Nitro-chiral’s latest title Slow Damage is now available in English. Given the developers’ back catalog, I had specific expectations for the game: erotic BL set within a cyberpunk setting, multiple branching paths and romanceable (or at least hate-fuckable) characters, and an abundance of gore, violence, and sexual trauma. About a third of the way into the game it has already checked all those boxes, and it’s the violence that’s most striking. While it would be overly simplistic to say Slow Damage makes no moral judgments about violence, it rejects didactic condemnation in favor of more nuanced examinations of the role violence plays in characters’ lives.

The game takes place in Shinkomi, a fictional ward of Tokyo, an indeterminate amount of time in the future. Narration throughout tells us that Japan is in a historic period of decline with poverty, homelessness, suicide, crime, and all manner of social ills on the rise. The protagonist, a young painter named Towa, views his life and society with a strong degree of apathy and seeks brief pleasure through cigarettes, drinking, and sex. With regards to the latter his tastes tend toward the extreme and painful, as do his various exploits in search of artistic inspiration. While other characters’ specific desires and hobbies differ, many of them share Towa’s interest in violence as a form of escape and/or expression.

Systemically, the aforementioned economic despair is an act of violence in and of itself. Beyond its roots in government action (and inaction), it serves as a springboard for extra-governmental worsening of living conditions as yakuza fill in the gaps left by the weakened state. Much of the citizenry then turns to fisticuffs as a means of letting off steam. There is a condemned district within Shinkomi where people meet up to take part in group street fights where the rules of combat are largely unspoken but nonetheless strictly enforced. There are also yakuza-sponsored fights to the death which wealthy spectators attend and gamble upon. Meanwhile other characters exercise violence as stress relief in less organized ways, whether by acting individually or as parts of small gangs operating with none of the honor codes found in more legitimized venues.

While Slow Damage establishes a variety of societal factors which spur on violent activity, it’s important to note that the game does not approach said violence with a didactic approach. There is never a sense that the developers are trying to depict all violence as morally bad, or even all perpetrators of immoral acts as irredeemable. In framing events from the perspective of Towa, a character who’s level-headedness sometimes crosses the line into sheer apathy, the game frequently rejects the potential to wag the finger at reprehensible characters. Instead, it imbues participants in violence with a degree of agency and nuance which would be difficult to convey in a story which approached the topic simply as a matter of victims carrying on cycles of abuse.

That’s not to say that said cycles are not present here; rather, Slow Damage is highly concerned with them. Such is the case with one of Towa’s primary love interests, Rei Izumi. His yakuza father effectively disowned him for being gay, thus contributing to Rei’s yearslong struggles with his sense of masculinity. Though it would be overly simplistic to call this the only stressor in Rei’s life, it was formative in shaping the adult Rei would become: an outwardly cheerful, feminine personality who spent much of his free time engaging in the aforementioned sort of street battles, reaffirming his own manhood.

This linking of queerness, conflicted gender expression, and violence goes a long way in deepening Rei’s character and painting his actions in a new light. Open embrace of violence as an outlet is all the more understandable when one considers that for Rei and his friends, violence is already a fact of life. He doesn’t just fight alone; he brawls alongside a trio of friends who all, though not explicitly described as such, read as trans and/or gender-nonconforming. In taking the initiative to enter fights of their own volition, they turn what could be a source of trauma into an avenue for queer expression and coping. Towa’s narration never states all this explicitly, but the presentation is clear enough that it doesn’t have to.

While Rei’s quartet engages in habitual violence, it’s never framed as a matter of them passing the harm that’s been done unto them onto someone else. Unless otherwise threatened, they only participate in matches where weapons and killing are deeply frowned upon. It’s only when violence leaves the boundaries of consensual brawls between well-reasoning people that it begins to become a problem. Several characters, including two of Rei’s friends, end up getting kidnapped and then subjected to group beatings. In this way the threat of true harm remains present, and isn’t just a spectre raised–but not confronted–by the cyberpunk setting.

Rei’s hardships only worsen when the father who abandoned him years ago uses him as a means of escaping yakuza retaliation. Heavily indebted to the yakuza due to an apparent gambling addiction, the father fraudulently transfers that debt to his son. If Rei refuses to pay off the debt then the yakuza will kill his father, thus putting Rei not only in financial hardship he never signed up for but also a moral quandary: is it morally permissible to walk away from a problem that was someone else’s making if walking away spells certain death for that person? The question is further complicated by the father’s abuse and his general moral depravity. Due to this extreme stress Rei begins partaking in the earlier mentioned high-stakes, high-return fights to the death. His behavior grows more and more reckless and suicidal, and how he resolves these conflicts depends upon the type of ending the player achieves.

Slow Damage features over half a dozen endings, each of which belongs to one of two categories: “Euphoria” endings or “Madness” endings. Generally speaking these terms correlate with the common concepts of “good” or “bad” ends in visual novels. Madness ends are quicker, ending the game prematurely and usually with characters in far from ideal circumstances. In Rei’s Madness end he continues to take part in life-or-death bouts with seemingly no desire to stop. He’s forsaken self-preservation in favor of money and creating a life of luxury for himself and Towa, who he now treats more like a personal art project than a lover. He’s taken to tattooing and scarring Towa in affordance with his own artistic whims, and generally treats Towa like a possession to come home to and revel in rather than a partner to live alongside.

Rei’s Euphoria ending, meanwhile, features much more standard resolutions for both his personal conflict and his romance with Towa. Once the specter of debt is gone and he puts his hatred of his father behind him, he begins confronting his issues with gender expression and sexuality. He works to adjust his self-image, adopting some more traditionally masculine mannerisms and visual codifiers (i.e. cutting his previously long hair and adjusting his manner of speech). It’s a complicated matter, and less about rejecting femininity itself than Rei overcoming previously held misconceptions about what sort of man a homosexual can be. He also develops a more mutually respectful relationship with Towa, and their final scene together features them discussing how much lies ahead of them that they never thought they’d be able to achieve.

While Rei’s Euphoria ending leaves him the happiest and healthiest he ever becomes throughout the game, it doesn’t falsely equivocate his reckless behavior late in the story with any of the other more therapeutic violence. Not only that, but it doesn’t even constitute a total retirement from street fighting; Towa’s narration informs us that Rei still takes part in matches sometimes, albeit with much more confidence and levelheadedness. Even in this good end the game seeds possibilities for future fighting, further acknowledging how embedded violence is in the fabric of the characters’ lives.

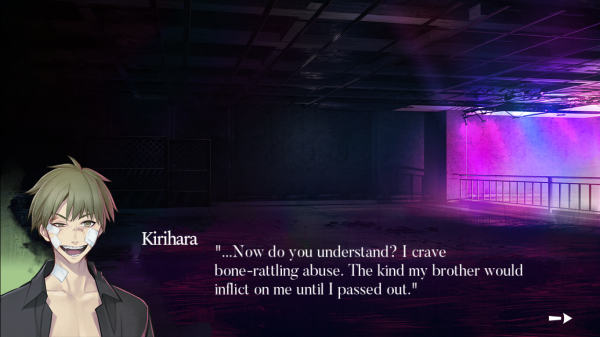

Even characters who commit far more clearly heinous acts of violence receive thoughtful exploration into their motives for their actions. One such character, Kirihara, is responsible for the aforementioned kidnappings and group beatings of innocent people. On paper he’s one of the least redeemable or sympathetic characters in the game. The narrative neither lazily wastes time condemning what is obviously reprehensible behavior nor tries to mount a defense of it, however. Kirihara himself tells Towa about his past, providing the player with context that fleshes out the character considerably but which, when delivered from Kirihara’s own sadistic mouth, never feels like a matter of deflection or excuse-making.

While Rei’s familial cycle of abuse hinges on neglect and rejection, Kirihara’s concerns physical violence. Growing up Kirihara was frequently beaten by his brother, who used him as a punching bag to vent his own frustrations. Though the victim, Kirihara grew to view said beatings as a means of helping his beloved brother feel joy. He framed his abuse as a sort of bonding experience, one which he deeply missed after his brother disappeared. He then began seeking out violence elsewhere in a largely failed quest to replicate the sense of intimacy he attached to his memories of the abuse. It’s a poignantly depicted unhealthy character dynamic, the sort of which can only be achieved when one rejects the notion of depiction as endorsement. Slow Damage is all the better for the developers’ willingness to explore unsavory behavior without wasting time proselytizing about it.

The intimacy which informs Kirihara’s violence is also extended to other characters, most notably Ikuina Takashi. Ikuina has desires which are truly, and I mean this in the strictest use of the term, problematic. He is fascinated with cutting flesh, and feels a compulsion to see what the resultant insides of wounds look like. He sublimates this desire for a time by engaging in self-harm and cutting up flowers for art projects. None of this is enough to sate his desires, and he begins to patrol the city streets at night in search of drunk or vulnerable people whom he can cut and, in an interesting complication, patch up afterwards.

Ikuina states that he gives his victims aftercare in the hopes that it will help them forgive his behavior. While his desire for acceptance is sincere, it’s clear that he realizes the aftercare doesn’t actually negate the harm he’s causing. He only assaults drugged and unconscious victims, never anyone who would actually have enough memory of the incident to evaluate his moral culpability themselves. As he explains his actions to Towa he is clearly troubled, stuttering before clamming back up and frequently avoiding eye contact. Though he may impose limits on the extent of his behavior, he is fully aware that what he’s done isn’t morally defensible.

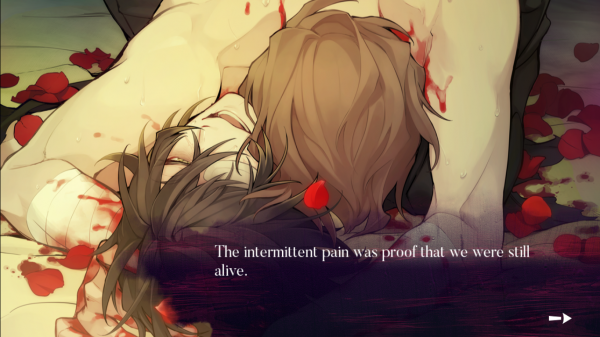

With that said, his moral failings are less interesting that what results from him meeting a willing participant: Towa. Provided that the player doesn’t trigger a premature Madness ending, Towa and Ikuina’s time together results in what is for all intents and purposes a sex scene sans the intercourse. Towa and Ikuina lay down together and take turns stabbing each other. Between stabbings they play with each other’s scars and rub up against each other in such a way as to stimulate their wounds and heighten the pain. The act is, however, a consensual and pleasurable one for both parties. Ikuina feels intense emotional catharsis at being able to enact his desires to an extent he never has. Towa, meanwhile, finds pleasure not just in the physical pain itself but also in helping Ikuina enact his fantasy.

Tonally the scene is very similar to the sort of blissful sex scenes that BL games often culminate in, including actual sex scenes in Slow Damage itself. If one were to hear the audio without looking at the screen, they would almost certainly believe they were hearing more conventional sex. Jazzy music plays in the background, punctuated by the characters’ moans and pants rising and falling in cadence with the intensity of their pain and pleasure. The composition of the artwork is similarly erotic, with lingering shots on Ikuina’s back as he hovers above and tight against Towa’s body. As if all this weren’t enough there’s also explicit confirmation that both men are erect beneath their clothes, but the act never shifts to standard oral or anal penetration. In this case violence serves less as a sublimation or substitution for sex and more as the sex act itself.

This sort of extremity is largely reflective of not just Slow Damage’s thematic concerns but also those of Nitro+chiral games in general. All the publisher’s releases to date have been aimed at adult players and featured similar themes of violence, sexuality, and horror, with events and plot conceits that are likely to shock some players. While such content might sound gratuitous when simplified to just a plot summary, the actual execution seldom feels shallow or haphazard. To me personally Towa and Ikuina’s mutilation-sex doesn’t feel too try-hard. Rather, the developers reject didactic moralizing in favor of subtler depictions of characters’ interior struggles with compulsion and violence. The final result is a scene defined by such striking intimacy that it marked the point where I switched from playing the game because it was a Nitro+chiral title to playing it because I was enamored with Slow Damage itself.

Though Slow Damage is brutally violent, it is not simplistically so. Its violence takes on countless forms from semi-organized street brawls to pseudo-sexual gratification to the oppressive structure of the governmental state itself. There’s heavy subject matter all around, but that’s the game’s appeal. By approaching violent conduct in multiple contexts and avoiding explicit proselytizing, Nitro+chiral delivers a layered and thought-provoking depiction of life amongst societal collapse. For these characters the everyday experience of violence is not optional, but how they negotiate its details and their involvement is.

Eric Cline is a writer, editor, and podcaster. Besides being a columnist for Haywire Magazine he also co-hosts the comic book appreciation podcast Chris and Eric’s Longbox Adventure. His Twitter is @ZorakRichardson.