Due Diligence: Putting the Pieces Back Together in Ether One

Leigh Harrison wonders what’s going on.

Dementia is a terrible disease that impairs brain function, preventing sufferers from remembering places, routines, and loved ones. It is a lonely and confusing affliction, leaving those it touches disconnected from the world and the people who care for them. Ether One is a puzzle game that attempts to convey dementia’s myriad symptoms through the withholding of information. It takes players on a disorienting journey through the mind of a sufferer, allowing us to experience the disease by removing our understanding of our surroundings. We wander around as if in a daze, unsure of what to do in the most mundane of situations, because the game never directly says what is being asked of us. Its adherence to a strict code of vagueness is effective in unsettling the player and conveying its message, but it also makes progressing through its challenges wildly difficult. In successfully portraying such a complex and nebulous subject, Ether One is a strange sort of triumph. It is simultaneously a powerful and devastatingly frustrating experience, one that I cannot wholeheartedly recommend but at the same time think that everyone should sample.

In Ether One you play as a Restorer, a futuristic mind-explorer who enters the fragmented memories of dementia patients and attempts to reverse the effects of the disease. Your employer, the Ether Institute of Telepathic Medicine, has designed a machine capable of generating 3D replications of memories, and it’s your job to explore those environments, piecing everything back together. You do so by collecting red bows, representing fragmented memories, that are scattered around each of the game’s four interconnected locations and combining them all to relive a particularly important lost episode. Upon grabbing each bow you’re told a little more about the the patient, 69-year-old Jean Thompson, her life in the village of Pinwheel, and what’s occurring at the Institute, which may or may not be running out of funding. You’re guided along by the wonderfully effervescent Dr. Phyllis Edmunds, who is incredibly smart, driven, and personable, but also so heavily invested in her work that she becomes increasingly volatile as your adventure unfolds.

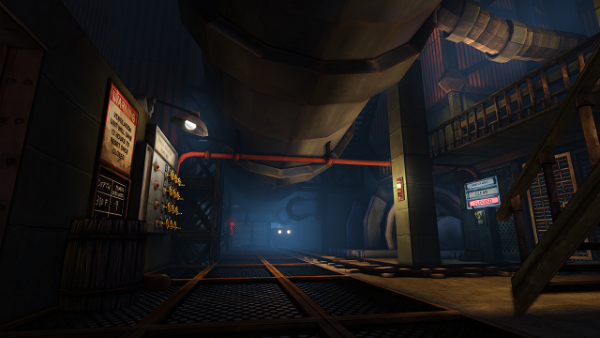

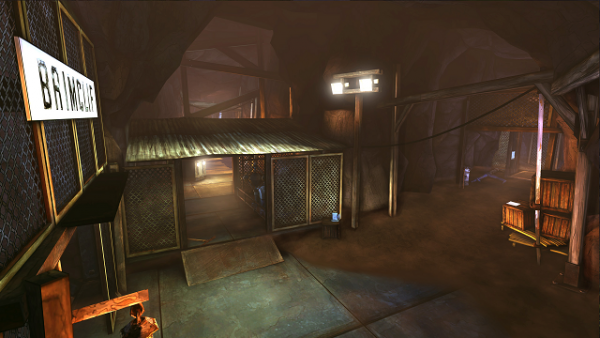

You can mainline Ether One in an hour or so if you wish, because collecting the bows is a very simple task. There are eight of them in each level, all sitting in very prominent places, and a cursory walk around an area will reveal the full complement. Once you’ve found them and relived the larger, “core” memory, the game loads you straight into its next section. Of the four locations available around Pinwheel, only three are necessary to explore in order to reach the ending. The game goes so far as to skip right past one of them, a jaunt down a spatially-chameleonic mine, in its entirety. There are still bows and whatnot down there, but the game doesn’t consider it essential to the experience and so forcefully makes it optional, asking you to seek it out rather than taking you straight to it, as it does with the others. It’s a strange move, one that mirrors the game’s discretionary stance on much of its own content, and as such roughly 98% of Ether One can be circumvented entirely. While the bows are integral to the main storyline, they are but a tiny part of the whole, with a deep puzzle element constituting the bulk of Ether One and harboring its true identity. In structuring itself around player consent rather than forced challenge, the rest of this admittedly difficult content is all the more alluring, its mysterious nature imploring the player to investigate further.

The real meat, then, is found in fixing up the game’s twenty projectors, which are another neat visual metaphor for Jean’s damaged memories. To do so you must piece together a chain of events specific to each projector’s location and thus help your patient remember a chapter from her life. The puzzles themselves are not abstract in the slightest; each of them is a very literal series of mundane tasks, but the way they are communicated to the player is refreshingly vague. It’s often not even clear what is being asked of you. You have to be patient and inquisitive to get along with Ether One, reading notes, diaries, and letters to slowly gather enough information to get a handle on each challenge.

One of my personal favorite puzzles took place in an industrial complex and involved poisoning a mine warden as cruel and drastic comeuppance for him not being a “people person”—not that I knew this was my task from the off, of course. My first clue was a series of notes passed between the miners in their locker room. The warden, it transpired, was working everyone ragged and not allowing his charges to take the Monday off to celebrate May Day, an inexcusable error of judgement in Pinwheel. A miner by the name of Sean V., the target of the warden’s strongest sanctions, had decided to do something about the situation. But what? He’d understandably not written that part down. However, in carefully scouring the surrounding rooms and absorbing all the information they held, I was able to laterally think my way to the answer.

Sean’s belongings contained the plans for the shower and locker rooms, and he’d marked on a weak wall, possibly with a mind to enact a spot of industrial sabotage to rescue the holiday. A neighboring locker contained a pilfered hammer, which I’d learned the handyman was looking for in a disgruntled open letter he’d left on the bathroom mirror. Hammer + wall gained me entry to a maintenance shaft, where someone (not you, was it, Sean?) had hidden a bottle of arsenic pills. Now, I knew the warden liked his coffee because he’d written its procurement into his morning schedule, so by this point everything was falling into place. His blue mug, optimistically naming him “The World’s Best Boss,” was hidden in another locker, and once I had that the rest was elementary: arsenic + coffee machine + warden’s desk = public holiday revelry.

I know that this sort of puzzle design is not new, but to see it constitute the bulk of a modern game is wonderful, particularly because it suits Ether One’s subject matter to a T. In being so vague, many of the tasks we perform perfectly channel Jean’s struggles with dementia, as our lack of information stands in for her loss of memory. The disease often robs us of our short-term memory first, meaning that mundane activities like using a phone or cooking become incomprehensibly complex. The puzzles are easy, but as players we aren’t equipped with the information we need to succeed. We look at everyday objects— a shelf of lightbulbs, a chalkboard, an industrial-scale grinding machine—and can understand that they do something, but we’re just not sure what that is and how to make it happen. We have to learn everything again and record, absorb, and note down information as best we can, despite it being disparate and confusing. Like David Bowie sifting through his chopped-up lyrics to “Low,” we’re constantly trying to make sense of a million scraps of paper, and in doing so we’re granted an insight into something resembling what it must be like to live with the disease. We compile notes of everything: people’s names, numbers, things seen in a cabinet, places, directions, anything could be important, but we’re just not sure. We write it all down because it’s the only way we can make sense of a sprawling mess of information that can’t be fully comprehend. These simple tasks often seem insurmountable as we run and re-run things through our minds, looking for patterns, clues, or phrases that might help us stumble in the right direction. In finding a way to represent the loss of memory as a game mechanic, Ether One gives us the chance to experience the lonely confusion of dementia, making every fixed projector, every rescued memory, a precious and gratifying achievement.

Even the smallest victory is hard won, and it cannot be overstated how difficult most of the game’s puzzles are. As you progress through its world you become increasingly aware of how best to exist within it, but this never results in you holding mastery over its challenges. You simply learn to adapt to its rules, altering your thinking to be in line with that of a dementia patient’s, as you tirelessly catalogue every aspect of your surroundings in the hope of making sense of them. That the puzzles are all rooted in rediscovering everyday routines makes you keenly aware of how fundamentally the disease alters our lives and how difficult performing even the most mundane of tasks can become. The more we accomplish, the deeper our insight into dementia becomes, as we increasingly lose ourselves to the disease’s all-consuming whims.

This understanding is further consolidated upon fully completing a projector. We are given a short snippet of one of Jean’s therapy sessions, the content of which explicitly mirrors our own experiences of the confusion the disease creates. As the projector displays the ethereal 3D image of an item linked to both the puzzle and its memory, Phyllis narrates the day’s successes and failures with heartbreaking passion. We also slowly learn more about Jean, her life, loves, adventures, friendships, and tribulations, as well as the dedication of the woman attempting to rescue the memories of an entire lifetime. But what is also powerful about restoring these snapshots of Jean’s life is the insight we are granted into the lives of the town’s inhabitants. In sifting through their collective thoughts to complete a puzzle, we are simultaneously given the chance to delve deeply into their personalities, and by the end of Ether One we’re intimately acquainted with dozens of fully-realized characters.

Take, for instance, the horrible warden. In a note tucked away in his desk and a couple of others scattered throughout the village, it becomes apparent that the mine is not financially solvent. The only way to keep it open and thus remain Pinwheel’s largest employer is to cut corners and work everyone harder. He isn’t, of course, at liberty to divulge this information, and he feels horrible for being in such a position, but he dearly cares about his staff and the wellbeing of the entire village. This level of narrative depth is replicated for many other characters, and despite never meeting another soul in the eerily deserted 3D reproduction of Pinwheel, there is a palpable connection to be had with many of them. You want to explore every corner of the village, read every idle thought committed to paper, and restore every single projector to working order, because the rewards for doing so are so rich.

It’s such a shame, then, that the game’s deficiencies conspire to upend its lofty ambitions. Some of the puzzles are just broken, both literally and in the thinking behind their execution. One of the game’s biggest flaws is that it doesn’t offer enough audiovisual feedback to the player, which is crucial when everything about the puzzles is so deliberately obscure. You press buttons and receive nothing to let you know what, if anything, has happened; you haphazardly place items on pedestals without a clue as to what you’re doing or where things should go. You might perform one step of a task out of its very specific order, but this crucial piece of information is not adequately communicated to you. The puzzles themselves are wonderfully designed on the whole, but there are instances where their implementation is disastrous. Their vagueness offers both mechanical challenge and intrigue, but in not clearly communicating progress to the player, they often fail to let you know you’re on the right track. This dampens the excitement of discovery and makes several sections unbearably and unnecessarily muddled as a result, which would undoubtedly turn away less intrepid players.

The game attempts to assuage some of the confusion by giving you a little tone when making headway with a puzzle, but this understandably only works if you’re going in the right direction to begin with. When you’re not, things begin to break down, and instead of working through each problem as the narrative and mechanical directives of the game demand, you begin to become suspicious, questioning whether you missed something or if the game simply isn’t able to hold up its end of the bargain. This could be seen as devastating, given the freedom of its structure and the thematic bent of its mechanics, but it can also be said that it takes those very themes beyond the confines of the game itself. Confusion is built right into Ether One’s design, but in most cases it is administered in a measured way, utilizing recurring visual motifs, item uses, and logical progressions to avoid blindsiding the player. When this doesn’t happen you begin to feel quite uncomfortable indeed, as if you agreed to the game showing you some of what it’s like to have dementia, and it instead decided to go much further.

This hypothetical reflexivity is even more pronounced when the whole game appears to crash if you load a savegame or fast travel (at least in the Playstation 4 version I played). Upon either of these happening, whatever is on the screen at the time almost fades to black, and then the whole thing just hangs for about five minutes. There’s no inspirational flavor text, no little spinning icon; the game just dies and then magically starts working again. This crashing is unintentional and jarring, a technical shortcoming that makes booting up Ether One an uncertain process, but it also further elaborates upon the game’s core themes of claustrophobia and confusion, taking them to a conclusion far beyond its own boundaries. It’s telling that wonky mechanics and technical hiccups can be so easily misconstrued as consciously obtuse design. Ether One creates an atmosphere of constant flux, where our very understanding of our surroundings changes as we uncover more and more information about them. It isn’t a great leap, then, for us to assume that the game could play with its own form as a means of furthering this intent. So while its greatest transgressions are simply (un)happy coincidences, it could be said that they add as much to the experience as they take away.

I applaud the six people who made Ether One. It is ambitious in the way that only truly inspired videogames are, and it is only able to be so impressive because it leverages the interactivity of the medium to stunning ends. But that is also where the cruelly ironic rub lies: it isn’t a good enough game in places, and that hurts the experience to some extent. It is so effective at channeling the ordeal of having dementia that in parts it can be too confusing for its own good. The vagueness of its puzzles gives us a striking insight into the disease, and through a combination of astute design, questionable implementation, and instances of technical failure, Ether One succeeds in its lofty ambition to recreate a mental disorder within a videogame. It is exhausting to play, because you’re never allowed, intentionally or otherwise, to fully grasp your situation. On a basic level, its rough edges undoubtedly make it a worse game to play than it could have been, but it’s hard to dismiss them entirely when they further embellish the confusion at the heart of its power. It is a game about not knowing where you are and what you’re doing, about vagueness and isolation. This is largely conveyed as the game intends it to be, but there are also moments where everything breaks down and this message is all the stronger for it. If it worked properly it would be a triumph. As it stands now, Ether One is deeply flawed, but all the more effective, and interesting, at the same time.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, makes DVDs for a living and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.