Due Diligence: Escaping the Den of Madness

Leigh Harrison makes a break for it.

It’s April 15th, 1912, and I’ve found myself aboard a ship, in a lavish, wood-panelled cabin. I’m slightly uncomfortable at being here, what with the vessel bearing the name Titanic and rapidly taking on water. My first instinct is to flee this fittingly coffin-like room, but alas, the door is locked with, of all things, a pair of handcuffs. I take in my surroundings for a moment, planning my escape. There’s a bureau in the corner, opposite the door. Next to that, on the expensively gaudy blue carpet, sits a little desk. Atop the table behind me is a vase of roses, a couple of espresso cups, a bottle of port, and a note. The number 1140 is scrawled mysteriously on a sheet of paper. A code, perhaps? I jog back to the desk for another look. There’s an electronic lock with a glowing green LED display preventing me from opening its drawer. On the sinking Titanic. In 1912.

The episode I’ve just described is the opening level of Escape Through History, one of the millions of “escape the room” games you can play on your phone, and it is exactly why I love this batty and incongruous genre.

Escape the rooms are pretty self-explanatory: you’re in a room and you need to escape. That’s it. At their heart, they are point-and-click adventure games, wherein you rummage about your surroundings looking for items, opening locked doors, cracking codes, and solving puzzles. Unlike proper point-and-clicks, which often have you traipsing all over an elaborate collection of locations, an escape the room is a much more intimate affair, constrained, naturally, to a single room. They also differ from their older sibling in that much of their challenge is built around hunting down items, rather than using them in ridiculous and esoteric ways.

Back on the Titanic, I open up the drawer after tapping in the code from the table. Inside, there’s an ornate golden key, which, like the rest of the room, is grotesquely extravagant. But where to use this overblown status symbol? Not to unlock the handcuffs barring my exit; that would be too simple. No, there’s more to this. After a bit of searching I come across a safe tucked down the side of the bureau. I use the key to open it and find exactly what you’d expect to be hidden in a safe on a luxury liner — the head of an axe. Those cuffs are sturdy, far too strong for me to get through by simply bashing them with a lump of sharpened steel. I’ll need some leverage. A handle, perhaps? Yes, a handle for my axe. After lots of faffing about and panicked dashing I find the missing piece. It was in the bed, hidden under a pillow. Quite why I took so long to find it escapes me; that was a pretty easy one. I snap the two bits together, smack the cuffs off the door, fling it open, and am greeted by a glowing portal of pure energy. I hold my breath and think of home. Then I jump through. Where will I land? Or should that be, when will I land?

The remaining fourteen levels of Escape Through History throw you around time with nonsensical glee, hitting you up with challenges in such celebrated locales as Billy the Kid’s favorite bar, Steve Jobs’ garage, and — my personal favorite — an off-brand TARDIS. There’s no real rhyme or reason to your journey; you’re just flung from one place to the next. Some of the locations are less historically significant than others: for every Da Vinci’s studio and Tutankhamen’s tomb, there’s an Area 52 (?), a rather old Spanish cave, or a dystopian Manhattan. Even with the freedom the game’s time–hopping framework affords, Escape Through History can’t really be bothered to uphold its initial premise of puzzling through notable historical episodes. Its levels just, well, exist, a bunch of rooms tenuously connected together with a paper-thin justification. It’s weird, disjointed, and great.

Structurally, most escape the rooms follow this half-assed template. The first level usually acts as a tutorial and gives a sliver of narrative. “You’re a robber; escape the bank;” “you’ve been kidnapped; escape the killer’s lair;” “you’re a member of the secret police; find the criminal, or, failing that, frame someone from a minority group.” This opening salvo exists exclusively as a framework over which to loosely drape the upcoming rooms. It’s a strange move, as these narrative tidbits don’t add a thing to the experience past a superficial layer of context that usually goes ignored anyway.

For instance, many horror-themed escape the rooms start thematically strong, but then just give up on the blood and guts in favor of a more kitchen sink approach to level design. Horror Escape, for example, looks like a Saw film to begin with. You run down dimly lit municipal corridors, finding clues hidden in all sorts of gross places, and unlock rusty, bloodstained doors as you progress through challenges set by your murderous abductor. The art direction is rather stunning for the genre, and the dank locales and long, ominous shadows create a genuinely spooky mood. Then, about halfway through, it all just stops. Concrete walled garages, sewers, and nondescript rooms become your prisons. Each has a filter stuck over the screen that gives the illusion of dark atmosphere, but the carefully constructed mise-en-scènes are a thing of the past. There’s one level, a bland office, where the only scary thing present is a mannequin slumped in a chair.

Say what you will about the genre, but the games are nothing if not efficiently made. The work of prolific developer MobiGrow/Goblin LLC/Trapped/Mobest (it’s got a few names) copiously reuses assets, ideas, and puzzle archetypes to the point of cannibalization. I’ve seen the same red car in a number of them. A four digit combination lock crops up time and time again, albeit in different colors. The same screwdrivers, spanners, wrenches, flashlights, crayons, sheets of paper, computer monitors, bowling balls, CD cases, and vinyl records litter levels, acting as clues, tools, or window dressing. Maybe that’s why that mannequin was kicking back in a chair: somebody made it years ago, for who knows what game originally, but there’s no harm in chucking it into another, is there? It adds nothing to the level, but it doesn’t detract from it either. It’s just there to fill an empty space.

A while ago I wrote about The Bureau: XCOM Declassified, a cover shooter where you fight aliens invading the U.S. in the 50s. Its early stages take place in locations steeped in vintage, picture postcard Americana, university campuses, homecoming parades, town centers, and gas stations converted into videogame spaces. This creates a strange disconnect between each level’s aesthetic and spatial qualities. Locations are meant to evoke a warm, largely vicarious nostalgia, but this is constantly at odds with the formal qualities necessary for them to work as shooter levels. As the game progresses, however, more and more of it begins to take place in alien installations and spaceships, removing the need for the terrain to be aesthetically congruous with the real world. By its end, the game’s levels are little more than collections of building blocks, spaces entirely focused on providing the player room to explore the mechanics. In stripping away all unnecessary visual frivolity, The Bureau lays its intent bare. It is interested in very little past the mechanical interplay between its combat systems. The visual treatment of its first half might be attention grabbing— indeed, much hooha was made over it during the game’s tortuous development period— but its true focus is really just how it plays.

I get this same feeling when playing escape the rooms. The puzzles are constantly the key element of each level. Once these are in place, then maybe a room will be filled out with meaningful trappings. This lack of care for aesthetics can prove to be hilarious, and yes, in a way it’s super lazy game making, but it’s also pure and mechanics-led, which I can’t help but find endearing. It brings into stark relief how unnecessary pretty graphics are past giving the player something to gawp at. There’s a touching purity to the escape the room that isn’t that common to find, even in the more straightforward realm of phone games. They are simple and cheap, but they are also strikingly unpretentious, uncynical, pulpy fun.

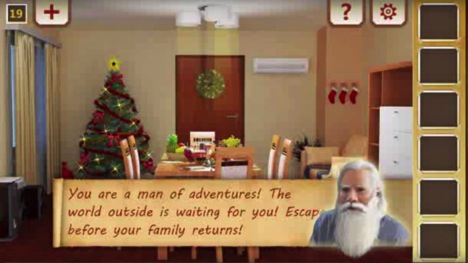

To this end, the horizons of the genre are beginning to expand, though ever so slightly, and it’s fast becoming the videogame equivalent of the classic B movie. MobiGrow et al.’s Human Life is one of the stranger releases, seeking to explore the human condition through the lens of escaping from locked rooms— which, when you think about it, is a rather bold move. In it, you guide an unnamed male protagonist through various milestones along the road of life. Each level comes with its own little story, delivered to you by a kindly, bearded narrator. Because of the very specific mechanical bent of the genre, your character is painted as somewhat of a miscreant, constantly running from responsibility at the slightest difficulty. As a child you’re grounded and must escape the confines of your bedroom. In college, you’re stuck in a dorm with the cops on the way. Your first job at a burger joint is very much below you, so you just leg it. Halfway through, the game treats you to a we gave up on the concept quadrilogy of levels. They begin by putting you in a crashing plane, then a politically incorrect cannibal tribe’s village, then in the cargo hold of a ship as a stowaway. The final chapter of the detour ends in a nightclub, with the game itself glibly questioning how this chain of events can possibly be considered contiguous. “You had to go through all these things to end up locked in a club? I know you can figure it out!” says the narrator with an almost straight face. I really appreciate this touch of audacity: it is both flippant and resoundingly knowing in the same breath.

And that narrator—it’s God! The God of the Christian faith is your guide in escaping from the predicaments your ill-advised actions have left you to. Your bong rips in college, your misbehavior in school, your inability to hold down jobs— God has been gently poking you to be a self–serving idiot since birth. In later levels His actions become even more morally questionable. “That’s the way to make big money!” He chuckles as you escape from a post-robbery bank vault. In the penultimate level he tells you to leave your family on Christmas Eve. Yep. You can’t make this stuff up.

Of course, escape the rooms can be full of bad touch interfaces, copious ads, nonsensical puzzles, clumsy hidden object hunts, and downright damnable design decisions. Yes, they are cheap, nasty little bits of software that bombard your phone with revenue–generating popups for as long as you’re willing to keep them open. Yes, they are badly written, often to the point of being unintentionally offensive both in style and content. Yes, they are lazily designed, repetitive pieces of almost-trash. But that almost is vital. Because of their slapdash nature and “it’ll be alright on the night” production qualities, escape the room games are, for me, the most genuinely interesting example of mass produced content for your phone. While other developers are busy cynically making match three puzzle games, clicker games, or endless runners, there are good people out there making simple little adventure games about unlocking a door. Around this core conceit exists a whole world of hilarious, confusing, infuriating, dumbfounding, and, on the odd occasion, genuinely surprising experiences. Escape the room games are pure oddball magic; play one with an open mind and I guarantee you’ll have a wonderful time.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, makes DVDs for a living and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.