Art Tickles: Caught Between Worlds

Taylor Hidalgo battles continuously with his D6, and often loses.

Gaming comes in many textures.

Some are more physical, textured analog tools such as clubs, rackets, cards, or tokens. They have structured shapes, courts, and tables. Their mechanics are built into the very objects they’re meant to be on. Table Tennis couldn’t be played without the tables and paddles, Poker needs a full deck of cards, and tabletop games needs the boards, cards, or dice to make the mechanics work.

Others are built digitally, with their mechanics and mechanisms organized and recreated through systems. Physics engines replicate the drifts of wind and gravity, lighting engines soften the shape and form of colors as they wrap around the soft rocks and metallic sheens of whatever atmosphere the game has built. Their controllers and peripherals make up the pathways that populate a game’s story, but they’re often done so invisibly. The vast oceans, the invisible walls, they all exist to mask the systems in play, to keep the actual goings-on of the mechanics hidden behind layers of obscurity.

Videogaming occupies a space built on a decidedly more physical history. The sprites, models, and random number generators that make up the digital systems are built on the back of paper, cardboard, and dice from their analog equivalents. All of the artifices and mechanisms were also plainly visible, explained, explored, and often debated among the players. Games were established not just by the aforementioned mechanics, but by the people playing them. The grand assemblage was, by and large, a multiplayer practice.

A gaming community is built around the idea of a communally loved hobby, a meeting of players and minds around an open forum, or a table between snacks and laughter. Everything about a gaming community, be it physical or digital, exists in the equally shared and communally loved practice, and it’s something that has made games better simply by giving players the opportunity to play.

Unfortunately, there exists a separation between tabletop and video games that isn’t easily bridged. In part because many videogames largely exist in a state of isolation, allowing a single player a single experience. The narrative, the structure, the mechanics all exist in service to the sole narrative or mode of play that the game has produced. There are exceptions, certainly, but videogame design is largely built around the telling of a particular story. Even in the case of online and multiplayer games, the primary mechanic is built in service of giving players a unified, direct experience.

Tabletop games, conversely, are as largely defined by the social interactions built in as part of the games’ mechanics. It’s the group that determines the nature of play, even if the mechanics exist to give guiding lines. They’re inherently multiplayer, as their very entertainment is built on the expectation of other players interested in participating, laughing, and playing along. Without that, tabletop games almost can’t exist in the same shape.

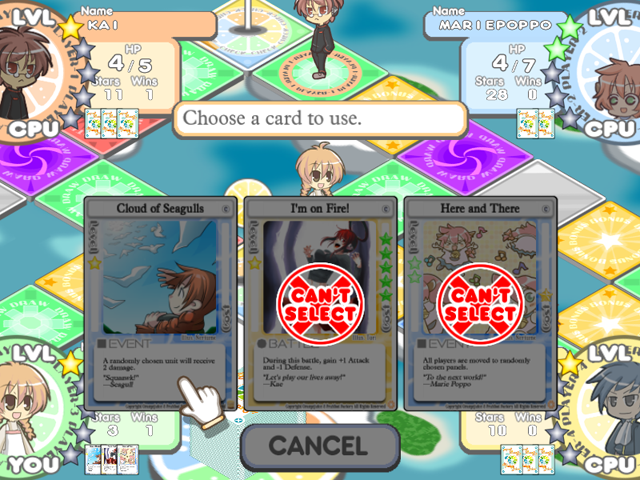

Their dependence on social interaction and participation put digital tabletop games in a bad place. Digital tabletop games, like 100% Orange Juice, are different due to their inability to fully bridge the separation between physical games and their digital equivalents. While their single player campaigns are appreciated, and in the case of 100% Orange Juice, lampooned, they’re still subject to the analog mechanics of an inherently around-the-table style of play.

100% Orange Juice, and games like it, don’t exist exclusively as video games. Their mechanics are too visible, giving the player access to the workings under the hood. There is no real surprise or experimentation, outside of the fact that the game itself will occasionally throw out curve balls. The mechanics exist to be shared during play, but it’s a sharing that isn’t entirely natural through text. It’s a sharing that almost impossible given the distance of having a screen and its digital game pieces rather than actually sharing of pegs and dice on a physical piece of cardstock.

They exist in a space between videogames and tabletop. Games where finding the social aspect is often unspoken, but just as integral to the game as the mechanics are. A place where a game can lose some of its magic even when doing nothing wrong, and where a Skype account or a Steam group chat is as important as rolling the dice. Having the ability to use group chatting programs like Skype, Steam, or Mumble is still perfectly probable, but adds a layer of obscurity that isn’t entirely bridged because it’s such a peripheral experience. It’s locked too far on the outskirts, outside of the realm of play and a part of pre-production and setup.

However, part of the charm of videogames like this is that they’re built on the setup. Maybe there is something deceptively integral in needing to get players together in one program, on the same page, and able to communicate before a game like 100% Orange Juice or Ticket To Ride can well and truly begin. Simply organizing such a thing feels natural in the face of such a gaming experience, perhaps even unavoidably so.

The emergent social communities these games inspire really speak to how special these games truly are. Even without the familiar trappings of physical objects and dice rolls, these sorts of videogames still manage to tap into some unspoken and somehow unavoidable sense of community that often organically emerges from them. The fact that gaming groups formed around games like Dungeons and Dragons isn’t a guaranteed, it had to emerge naturally at first in order to become a trend. Perhaps having a digital game make it happen anyway is testament to just how innate the sense of culture and community these games have is. They almost can’t exist any other way.

As a result, maybe digital games are just a different flavor of a familiar texture. Something new, exciting, and in the same way, also reassuring and intimate.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer by hobby, grasping at the edges of professional work. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter and his blog.