The Superheroic Vertical

Marcos Gonsalez watches over Gotham.

Up and above. Wings spread out, elongated and mighty, soaring high above the skyscrapers of Gotham. Drones dot the airways of this city of perpetual night, surveilling all. The drones are my enemy, however, and I avoid them to abstain from combat, instead wanting to coast through the velvety blackness, the wisps and curls of Gotham air. In the distance is the Bat-Signal. My calling, the reas—

A monstrous bat creature roars into my face. It swipes with an immense wing clawed at the end. A jump scare: Man-Bat appears. He flies off into the night, and I think of him as somewhere out there in Gotham, stalking the airways, in search of pray. The advantage of the air is one I no longer have to myself. He becomes a new side mission, a new enemy to takedown in Batman: Arkham Knight.

Gotham is sprawling. It feels expansive. It feels like a world in and of itself. As a New York City-dweller for the past ten years, I no longer feel that sense of awe for urbanity. The mouth open on the first days living in a city. The rush of riding across the Brooklyn Bridge in a yellow cab, or an impromptu photo session in some Chinatown back alley. The aliveness when looking down from one of the tallest high-rises on Wall Street. The grandeur at night of all the lights, the thickness of the air, the starless sky. My sensibility has adjusted, absorbed even, the scale of the city. It feels all too ordinary.

But in Batman: Arkham Knight I feel that wonder again. The immensity of architecture, the way a building can induce awe, a bridge’s length can excite. The lights from above forming a network, an intricate chaos. This city experience is different, however. The vantage I get playing as Batman is not one I have ever had as a city dweller. I have never crouched on a building ledge overlooking the sights, or tightroped from one building to the next. The landscape of the game feels like possibility. Limitless in scope because of my ability to scale its heights, to traverse its depth, to fly through its airways. I feel superheroic.

The first game in the series, its environment bound to the island of Arkham Asylum, didn’t share this sense of scale. That world was horizontal, unlayered, static. I felt a sense of being led to the next mission. There was little room for exploring and getting lost. With the release of Batman: Arkham City, and then Arkham Knight, the world that is Gotham, a city so many of us have fallen in love with in comic books, television shows, and films, becomes real. It is the first time we get to experience what it is like to be the caped crusader in his environment, in his city, as we fly through it, crouch and dangle from its buildings, lose track of ourselves as we explore.

The world turned vertical-side up.

The scale, and the sensing of scale, that is Arkham Knight, is made possible because of Batman’s abilities to defy the spatial limitations most ordinary people have placed upon them. Batman can fly short distances seeing the city from an aerial view because of his suit, a view normally only accessible by helicopter or airplane. He can stare down upon Gotham from the heights of Wayne Tower because his gadgets allow him to do so. When he needs a pick-me-up he ziplines from a building saving him from a cataclysmic fall. He can nose-dive downwards to give him some velocity for an upward leap, allowing him to continue soaring, continue sightseeing. The city, as a landscape, as a concept grander than a puny human, simultaneously expands and contracts from these movements and vantage points. The city becomes sublime because as Batman, with all his cunning, his gadgets, his ingenuity, his butler Alfred, the constraints of space and scale can be bypassed.

These aspects of the game make playing as Batman feel superheroic. Extraordinary in a more than human sense. Our vision is above the city, above the people, above it all. The bird’s-eye view enables what could not have been experienced before: the feeling of superheroism. Pressing the buttons on the controller is power.

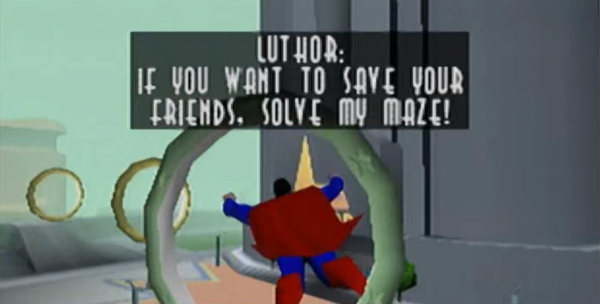

This feeling of superheroism can find its roots in the car-crash of a game that was Superman on the Nintendo 64. A game I bought as a kid because I wanted to feel superheroic, I wanted to fly. As soon as the cartridge was plugged in — boom, disappointment. The flying mechanic was clumsy, and hard to maneuver. Flying through the ringlets in the air was immensely frustrating. This was one of the few examples we had of what it might feel like to be a superhero, and it didn’t feel very superheroic.

Developments in production makes possible the experience of being superheroic as it is rendered in Batman: Arkham Knight. Realism saves the day when, in the past, the highly pixelated body of Superman, or the blocky skyscrapers that comprise Metropolis, or the clunky movements of Superman flying, or the two-dimensionality of games like Batman Returns on the Super Nintendo, gives away the simulation. Realism, and the details accompanying it, compounds the feeling of being a superhero: the rumbling of the controller when we tailspin towards the Earth, the freefall, the danger, the thrill of it; the cutting sound of wind beneath our wings, air turned material, palpable, strong, as we fly against it in the night; or being plucked out of the sky when enemy bullets hit us. The environment is alive and, like all environments, it has its physics, its rules and laws.

But realism can only take credit for so much. Ultimately, it is verticality which affords the sense of superheroism present in the game. We can go from street corner to skyscraper, back alley to bridge within seconds. We can glide between water and land without ever having to step foot on the ground, or get our suit wet. The tiers of space that constitute Batman: Arkham City’s layered environment are meant to be traversed, breached. The buildings of Gotham are meant to be obstacles, and, more importantly, obstacles that can be overcome. Their immensity, their Cyclopean size, their larger than life attitude, is finger food in comparison with the other challenges the game gives us. The city and its design—the dangerous heights, the speed and velocity of the city, the variations in neighborhoods—becomes something to be mastered. We know we are superheroes because skyscrapers are nothing in our way: concrete playgrounds.

In the world outside of such a video game, humans are bound by horizontality. Humans can only jump so high, after all. If we do want to experience verticality, the movement up and down between levels of space, it, most of the time, must be bought, an enhancing appendage. Skydiving, helicoptering to the tops of mountains, taking an elevator to the top floor, rock-climbing. And, still, these things are done with a level of security and protection that reminds us once again we are all too human, that we are but flesh and bone. Breakable. The limits of human bodies are overcome, as are the limits of space and time, in a game like Batman: Arkham Knight.

Being superheroic, and the sense of feeling superheroic, is bound to the environment—we feel it because the smallness of the city, the ease at which we maneuver through it, tells us so.

Verticality our Power Ring, our adamantium, our utility belt, all our own.

They are small from this high up. Muscled arms holding guns, masked, their big and burly bodies minute from this distance. I have the upper hand. They are unsuspecting. The night is thick, and I blend into it. They will feel my might.

I glide down, and down, and down right into one of the men. Instant KO. I seize upon the element of surprise and drill my fist into the face of an enemy close by. Another tries to land a blow, and I counter. Then a knee and a kick and a barrage of limbs outward at all the others. A flash of darkness across the screen taking down seven or so enemies within a minute. No challenge at all.

This is just one of many of the encounters with groups of baddies across Gotham. They wait in their clusters, huddled and bickering amongst one another, unknowing I am above ready to strike. My Justice a deliverance from the sky.

Batman can afford such vertical advantages while the everyday baddie cannot. He is, after all, a Wayne. The game puts us in the position of a character who has access to such vantage points. A vantage point only those seated in governments, those operating drones from military bases, those with corporate pocketbooks, those men of the world like a Bruce Wayne, men with money and men with “good” intentions, men who give thousands upon thousands to charity yet produce the very conditions which demand charity to be given, can afford. Verticality is costly.

Arkham City is designed for the player. The monumentality we associate with cities —the awe-inspiring verticality I felt when I first moved to New York — soon gives way to a sense of belonging, familiarity. As Batman, Gotham is my city. In series like Assassin’s Creed the cities and environments are designed as a challenge—it will make or break them. The city is a playground, no doubt, but a playground that must be approached with caution, strategy, because its scale dwarfs the human character. The player in Assassin’s Creed surveils, much like Batman, much like government or military agencies, from the tops of buildings, the aerial view, but this surveilling is done from below: the player is an assassin. Their justice is illegitimate, uncondonable, therefore they must move stealthily, risk exposure, moving about the city and countryside knowing they are not the good guy. The design of environment, then, becomes a genuine obstacle, an aspect of gameplay that the player must be aware of, thought upon.

In-game, and out of game, verticality is monopolized. Batman has control over the sky, and the in-between of sky and ground, because his gadgetry allows him to. Man-Bat is the only other character who threatens this control but he is an easy enemy to take out. He poses no real threat. He is no challenge one must do-over. In the world outside the game, the control over the skies is something big businesses and big governments have control over. The land surveyed in infrared, in HD, in macro and in micro. Picking out who is in need of justice, who is villain and innocent, whose life will be spared and whose will not. Aerial positions, and easy maneuverability between sky and ground, legitimize and authorize which vantage point tells the story. Much like Batman in the sky.

In the vertical zones there is no real threat to those who have adapted themselves to occupying it. Is Amazon a superhero? Is the United States military superheroic? Is Batman’s existence justified? These entities can afford to dominate the verticality of space. They need to in order to expand their reaches, their wealth, their governance. Land and sky, and all the in-between, is theirs because they have the resources in which to make it theirs, in which to structure the narrative of verticality as one that is in need of protection. Post 9/11 discourse, a discourse situated on the threat that violence can come from any spatial point, any distance and any vantage point, has helped to concretize this fear. Amazon or the United States, like Batman, like a Bruce Wayne, have legitimated their presence on the fear that the skies and the airways need to be monopolized and protected from threats, to make life easier and safer, most especially from the threat of racialized bodies, or foreign bodies, or bodies deemed criminal. To be superheroic, to give nuance to who is good and bad within the city, how to write the narratives of just and unjust, deserving and undeserving, moral and immoral, distinct from the logics of verticality as they are inscribed by state power—how?

Verticality is on my brain during this second playthrough of the game. I as player am occupying the privileged position of governments and militaries, the funded and the elite, those who make themselves judge, jury, and executioner. In this pixelated universe, maneuvering between skyscrapers and factories and bridges, this vantage point of verticality feels right. The bad guys feel like real bad guys. Those who injure, who hurt, who terrorize because they are evil incarnate. Evil is perceivable from this height. This vantage point gives the authority to make evil perceivable.

But the world isn’t this black and white.

There is a story behind every villain, every Joker, every Killer Croc, every Catwoman.

The dark sky reaches outward, seemingly limitless. Neon lights, a clock tower, the Bat-Signal. A drone hovering in the nearby distance. This gridded expanse, its reaches and its depths, the lines and angles, an unprecedented vastness.

Something else is in the sky. Something large, inhuman, with a wingspan. It’s Man-Bat. The only other enemy who occupies this in-between zone, this urban verticality. In the name of Justice, in the name of the superheroic, I plummet downward in his direction. Arching towards him, cutting through sky diagonally, fully owning the vertical landscape.

There is only room for one dark knight in the sky.

Marcos Gonsalez (@MarcosSGonsalez) is an essayist and PHD candidate living in New York City. His essay collection about growing up a gay son of an undocumented Mexican immigrant and poor Puerto Rican mother in white America, Pedro’s Theory: Essays, is represented by agent Lauren Abramo and is currently on submission with publishers. His essays can be found at Electric Literature, Catapult, Unwinnable, and The New Inquiry, among others, and he writes a column on the materiality of video games for Cartridge Lit.