Tap to Play

Mahreen Fatima taps her keyboard in rhythm.

Your heart starts pounding as you walk into the ballroom. Your friends have already claimed a table, but it’s filling fast. Squeezing into the last seat, you take a deep breath, ready to spend the evening chatting. Suddenly the music changes and an upbeat rhythm coated with snares and subs unapologetically intrudes upon your conversation. Everyone gets up, and though you try to slip away unnoticed, you’re dragged along to the dancefloor. Embarrassed, you explain that you don’t dance. Confused expressions and a laugh of disbelief: of course you do, you just need to feel the music.

When you get onto the dancefloor, you notice that no one stands still to the beat of the rhythm. The guitarist strums with his whole body, the dancers jitter to the beat, and through the movement all around, the song begins to envelop you. While you can’t yet feel the beats properly, you know your surroundings are made of frantic energy and vibrations from the people dancing. Finally you see it: the movements and flow of bodies in time with music. A sudden wave of elation hits as you are captivated by watching the lively scene unfold to the thump of the beat.

Interwoven in their presentation, music and visual art embolden and enhance each other. Games, blending different artistic forms of expression, have the opportunity to subject players to such a combination of sensory experiences, to the benefit of each individual part. However, their main focus has traditionally been on the visual aspect of this mix. While games are frequently lauded for achieving higher visual fidelity, exploration of their musical potential is seen as secondary in the race to sate the demand for better graphics.

Subtly creating atmosphere is important, but music also has the ability to benefit other aspects of the game, and influence visual elements such as characters, environments, and mechanics. The rhythm genre, aware of this potential, created innovative games that toy with the possibilities sound affords. Much of this experimentation now happens in a lively indie scene playing with the relationship between auditive and visual elements to present games in which the player takes cues from the sounds around them.

Sometimes, the player is the musician. Tying sound to movement, players in the rhythm-platformer game BIT.TRIP RUNNER create music by hopping and sliding along its automated path to dodge obstacles and snatch gold and power-ups. By allowing the character to be the visual representation of a song, music enjoys a stronger presence in its interaction. Rhythm games, especially those without difficulty settings, may assume that the player has prior experience toying with tempos and beats. This assumption can be a big obstacle to players who are new to the genre. The alternative portrayal of sounds enables the player to follow along just as easily if they were oblivious to the beat.

The visualization of music lets players appreciate it on a level they may be more familiar with. Players who don’t have musical inclinations outside of games could get a sense of what others enjoy about it when its qualities are repackaged this way. Connecting music to other senses also means detaching it, at least in part, from the perception of sound. Those with hearing disabilities could potentially experience its joys through the bridge built between different senses in these games.

Unfortunately, BIT.TRIP RUNNER loses its rhythm by overstimulating the player. Each level starts with a clear focus on the little pixelated character, but distracting background elements such as brightly-colored planets and passing stars gradually take away from it. Until checkpoints are introduced in BIT.TRIP RUNNER 2, players might also find themselves increasingly frustrated with its trial and error approach. Progress may feel unattainable when the longest stage, “Odyssey”, is featured in the first third of the game.

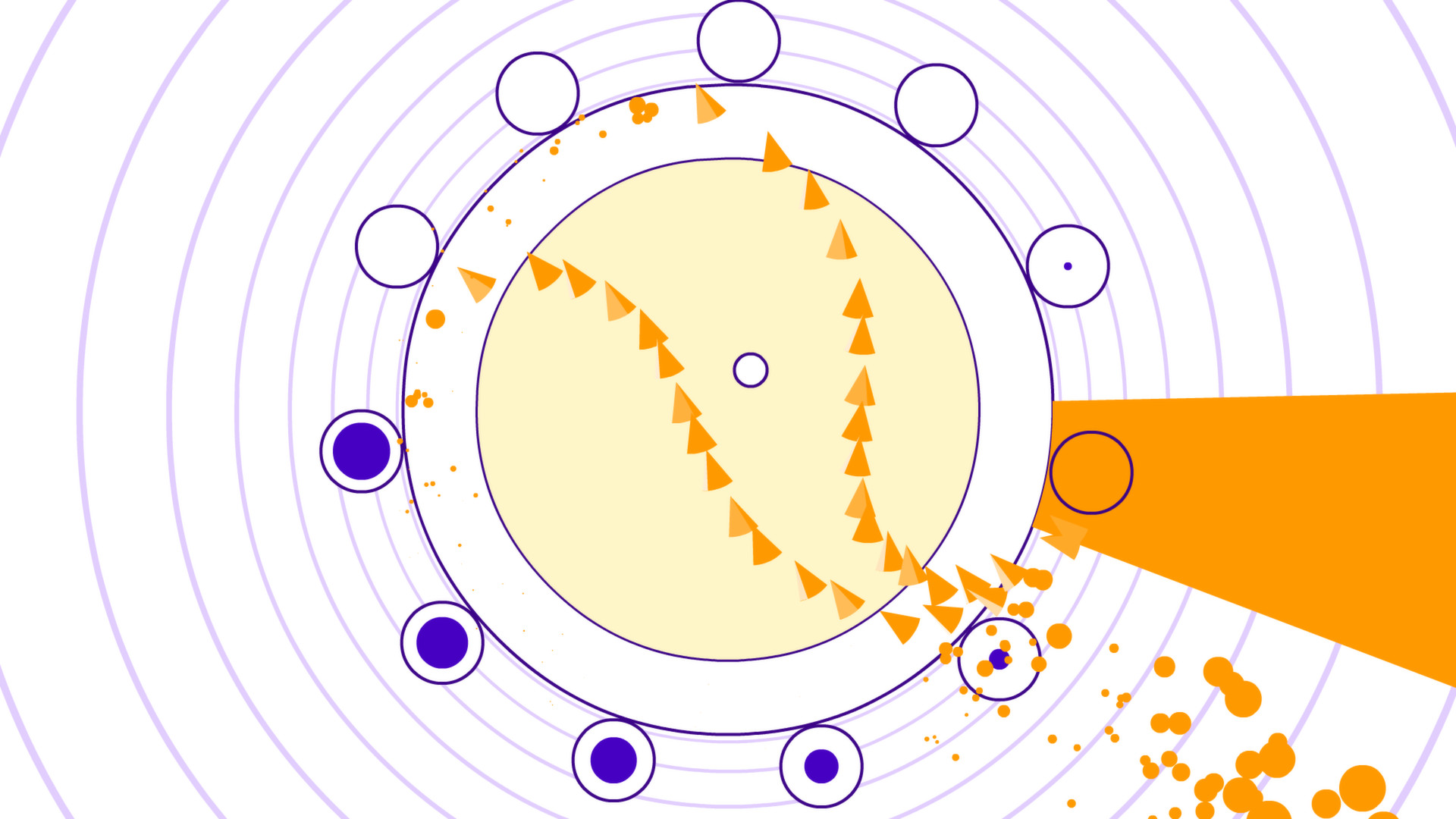

Another mix of genres and styles, Soundodger combines bullet hell games with rhythm games to create a minimalist dance of dodging threats timed to the beat of the tune. The simple mechanics allow the player to easily get lost in the flow of the songs and movements, encouraging a spaced-out state of immersion. Soundodger is also effectively programmed to allow users to play their own songs, creating threats by the tempo and beats of the tune.

Just as media focused on visual arts tends to keep music in the background, rhythm games tend to benefit from providing minimalist visual environments to make them easier to take in and keep players’ attention trained on sound. Unlike the distracting vistas of BIT.TRIP.RUNNER, Soundodger’s colorful blips make it easy to focus on interacting with the music.The game uses strong contrast and patterns that draw the eye to the center of the screen, telling the player where to keep their attention.

The little trick that Soundodger and games like it have found is that the music genre plays very well with casual games. It’s easy and relaxing to simply sit down and pass half an hour on such a game between doing other things. Unfortunately, this also makes Soundodger a relatively forgettable game. Bullets and threats pass by, song after song, and the repetition goes from being comforting to being tiring.

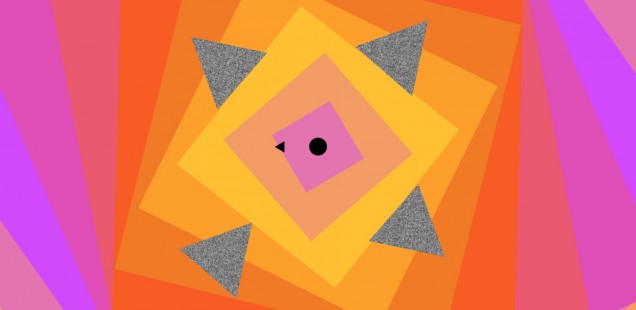

Combining the visualization of music with minimalist environments, 140 displays its skill with music on the stages of a platformer. What sets this game apart from other rhythm games is the level of integration it offers to music. While BIT.TRIP RUNNER and Soundodger stick to just the beat, 140 doesn’t waste any notes. Snares make certain sets of platforms appear and disappear, subs make areas grow and shrink, and the melodies move the objective orbs around the stage. The player must read these cues by constantly paying attention to all parts of the song.

140‘s masterful use of music affects much more than a few platforms and orbs. As the player progresses through levels and stages, the music changes the environment as well as the color scheme. While the game tries to keep to its minimalist style, the subtle would-be city skylines passing by in the background add to its most prominent layer. Luckily, the game lets the player pick the pace they move at, so they have ample time to pause and indulge in both the music and the environment.

140 is much more than just a platformer. Combining the sum of the parts of both a platformer and a rhythm game, the player must be patient in figuring out movement patterns and boss battle tactics. Strategy becomes necessary as it is revealed that each of 140’s boss stages uses rhythm in a different style. As the music kicks up and the projectiles start to fly, the player must trust in the music and watch the boss dance to see what follows.

Experimenting with new elements and mechanics is the first nervous, off-beat step on the dancefloor games are taking to string musical moves and mechanics together. Games with more than one sensory application have the potential to involve players in rich forms of interaction. This, however, is not meant to belittle what other genres do with music. Horror games, for example, would not have the psychological control they have on the player without the dynamic songs and sound effects they feature. The genre necessitates relying on music to create atmosphere and manipulate the player, albeit in a very different way. Other genres could benefit from further experimenting with sound to see what applications they could also glean.

We want games to advance. We want better graphics, larger worlds, and epic storylines. We want our characters to have rich backgrounds, the art styles to be unique, and the environments to be immersive. But game development, like any craft, needs a strong foundation in order to thrive. While it seems that developers are mastering features such as quality graphics and integral mechanics, they are overlooking some of the more basic tools at their disposal. Further innovations with sound would allow for richer games with stronger relationships between audiovisual elements.

Perhaps then, videogames will take that next step and land perfectly on the dancefloor – on cue, on beat, and in rhythm.

Mahreen Fatima is a creative person, game designer, writer, and musician. She started with a viola, which spiraled out of control, leading to a three-car pileup of playing instruments, painting digitally, and writing opinions. Her words can be found on Twitter.