Play Therapy

Zachary Brictson considers Final Fantasy VIII’s improbable quest to get its players to put down the game.

Despite their current fascination with sharing and online interaction, videogames remain something of a reclusive hobby, one that implies some level of social ineptitude in its participants. The many gamers who manage to combine this pastime with a healthy social life have found this stereotype hard to shake and, in their passionate defense of the medium, tend to overlook that there might be a shred of truth at its core. It’s more than petty stigma in Japan, where introversion has risen to concerning, sometimes disastrous levels, leaving many young individuals in unknowing confinement to a solitary activity, to an industry that both embraces their insecurities and directly exploits them.

Initiating a process of healing seems a daunting task, reaching out to those who willingly seclude themselves within computerized escapism almost futile. In response, developer Squaresoft, recognizing a social problem their own products have helped foster, tried to reach out to digital hermits through one of the few avenues of communication left to them: games. In what may be their most bizarre creation, Square released Final Fantasy VIII, an RPG to hijack its audience’s desire for extreme, self-serving fantasy and steer it towards a message that addresses their own repressed youth.

Around the time of Final Fantasy VIII’s release in 1999, public concerns over the stunted development of children were at a peak, Japanese media being especially fascinated by the phenomenon of hikikomori (lit. pulling inward, being confined). While the term was primarily associated with cases of extreme seclusion – adolescents and young adults not leaving their living spaces for weeks, months and even years at time – it brought attention to anti-social behavior in general. With the videogame industry in Japan naturally under massive scrutiny, Final Fantasy VIII appears an obvious reactionary move, one giving the series’ new director, Yoshinori Kitase, a chance to experiment and lead the franchise from its roots of charming fantasy and into more humanistic realism.

Disguising that realism as fantasy, however, was necessary for the game to sell, and thus to reach the audience it would later hold under interrogation. This leads to the stark juxtaposition of the real and the unreal that Final Fantasy VIII is designed around. The game is about a cast of teenagers attending school together, relatable to Japanese players in its introduction to bullies, gossipping girls, blowhards and the studious. With snappy instructors and uniformed students running late to class, the atmosphere is completely down to earth, but contrasted against true outrageousness: This is no ordinary school, it’s a training ground for elite magical soldiers. Because who would have bought the game if it were otherwise?

In effect, players will first take a field exam involving the invasion of a beachside town under military occupation, and then return to school, nervously awaiting their grades to be posted. A giddy and immature group of high-school students caught up in the most grisly form of military regiment – the premise is too brazen to be taken seriously, but precisely the type of fantasy a young, male audience might be attracted to. In another segment, the mission is to help a group of rebel misfits commandeer a speeding train and take a key political figure hostage, if not potentially assassinate him. Despite what should be depicted as a particularly morbid ordeal, the planning stage involves the kids calling for group huddles, conspiring over crude, homemade dioramas, taking naps and complaining of tummy aches, the entire scene a parody. Of what, the player has yet to guess.

In effect, players will first take a field exam involving the invasion of a beachside town under military occupation, and then return to school, nervously awaiting their grades to be posted. A giddy and immature group of high-school students caught up in the most grisly form of military regiment – the premise is too brazen to be taken seriously, but precisely the type of fantasy a young, male audience might be attracted to. In another segment, the mission is to help a group of rebel misfits commandeer a speeding train and take a key political figure hostage, if not potentially assassinate him. Despite what should be depicted as a particularly morbid ordeal, the planning stage involves the kids calling for group huddles, conspiring over crude, homemade dioramas, taking naps and complaining of tummy aches, the entire scene a parody. Of what, the player has yet to guess.

From one ridiculous set piece to the next, Final Fantasy VIII then becomes convoluted. Its narrative introduces time travel, evil sorceresses, summoned mythical beasts and trips to space, shamelessly changing the rules of its own world at the drop of a hat. Even the game’s ludic elements, that is, its very mechanisms, offer players a way to lose themselves in pointless entertainment. To make their characters stronger, for example, they must “draw” magic from the creatures they encounter, an arbitrary and pointless system that allows players to improve their party without end, even though the game’s difficulty will adjust to any level of grind. Thus, wasting time is a completely voluntary addiction.

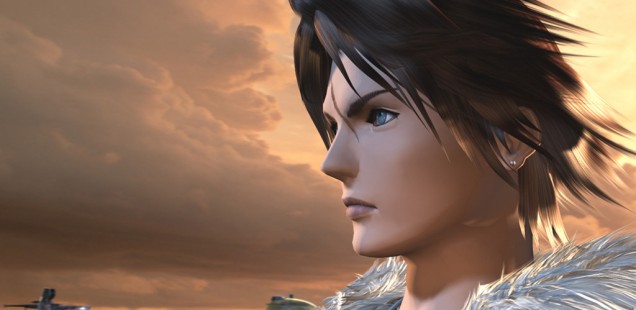

It is this level of fantasy overload that allows Kitase’s Trojan horse to slip through the defenses of his audience, and it comes in the shape of main protagonist Squall Leonhart. An innovation for the series, Final Fantasy VIII implements not only typical text box dialogue, but text boxes unique to the main character’s own thoughts. Squall doesn’t talk much, he is an introvert of the kind other introverts would like. His reserved demeanor makes him stand out as more mature than his companions and his thoughts portray an air of superiority. The same archetype often features in Japanese anime, manga, and other games, he is the popular glorification of someone too cool for the nonsense around them, being a powerful super soldier, no less.

But as the game gradually loses its grip on reality, Squall’s character becomes unsettling. His true mental state is, put lightly, troubled. As those around him seek his help, advice and leadership, he goes from being dismissive of their problems to becoming increasingly frustrated by them. It is at these points where Squall’s silly and incapable peers will break character and directly address his flaws in suddenly mature lecture, reading off uncanny bits of advice about how “you need to learn to express yourself.” These occur as fleeting moments before the game resumes the schizophrenic fantasy players find comforting.

But always pestering Squall is the love interest, a girl named Rinoa. Their short-lived meeting in a ballroom celebration for Squall’s graduation has Rinoa tugging him onto the dance floor, despite his “I can’t dance” attitude of disinterest. But here and throughout the game, Rinoa is not only pulling Squall from his comfort zone, but players out of their own escapism, placing both in nearly all of the game’s pivotal encounters and stressful decisions. Out of the role playing game and into the spotlight, Squall is, by the latter portion of the experience, revealed to be a complete wreck of a dysfunctional youth, in desperate need of the girl’s companionship.

But always pestering Squall is the love interest, a girl named Rinoa. Their short-lived meeting in a ballroom celebration for Squall’s graduation has Rinoa tugging him onto the dance floor, despite his “I can’t dance” attitude of disinterest. But here and throughout the game, Rinoa is not only pulling Squall from his comfort zone, but players out of their own escapism, placing both in nearly all of the game’s pivotal encounters and stressful decisions. Out of the role playing game and into the spotlight, Squall is, by the latter portion of the experience, revealed to be a complete wreck of a dysfunctional youth, in desperate need of the girl’s companionship.

Appropriately, this epiphany is realized in a scene in outer space, the two characters privately removed from the world below and, in essence, the entire game. It is the climax of fantasy, a plot movement void of any real intelligent bearing, sure to frustrate players still attempting to follow it, oblivious to the idea that they, too, are being pulled out as objects of study. During this seemingly cliché tryst Rinoa brings up Squall’s childhood of all things, using the present moment of intimacy to address his upbringing. “Didn’t you feel safe and secure being held by your parents?” she asks him, as he awkwardly deals with having a cute girl in his lap for the first time. Here players are reminded that Squall is, in fact, an orphan, abandoned by both his parents and left traumatized when a sister figure also left him at a young age. This heavy dependence at an early age, sheltering followed by abrupt abandonment, is implied as the cause of Squall’s social ineptitude, his sudden onset of anxiety and his stubborn refusal of intimacy and help from others.

Relayed through flashbacks, this character flaw of Squall proves to be the most stinging criticism of the player, forcing them to reflect on why they’ve been lured to this point to begin with. Of course, whether that reflection helps remains to be proven. It would seem more likely that players might be annoyed at this point, or even had their pride damaged by the destruction of Squall, travelling back down to earth to bitterly prepare for an ending showdown with the final boss. And as they pounded away with their high level weaponry and magic that they’ve worked so hard for, what remains of the fantastical shell is shattered. When a villain’s final words are so far removed from the game world as to desperately plead to “reflect on your childhood”, the game truly ends as a sort of personal letter from developer to player. A letter saying that now, perhaps, it really is time to put the controller down.

Zachary Brictson is a Computer Science graduate from Northern Illinois University who chooses to write about games rather than code them, contributing to physical publications like The Printed Blog, sites such as Playstation Universe, and his own blog, Up Magic.