Modern Teddybears

Stewart Melville on videogames as an emotional surrogate.

It’s fairly common for people to have owned a teddy bear or similar stuffed toy at some stage in their lives. In fact, a survey by Travelodge found that over half of Britain’s adults still possessed a teddy bear from their childhood: it’s an emotional crutch that seems to be difficult to let go of. Teddy bears are a an effective method of countering the inevitable stresses created by accumulative social exclusions and day-to-day life.

As an interactive medium with a potentially high level of player involvement, videogames seem to be ideal for developing similar attachments. Possessions play a very powerful role in influencing human behaviour, and the act of acquiring or adopting a possession is often twinned with a strong need to defend and safeguard it against threats. This perhaps explains why some people can get quite defensive when an older game is criticized, or when a remake does not stay true to its source material.

But objects are not the only potential possessions for the psyche to latch onto. Time and place can also be something that people collectively claim, like ’90s kids’ and their cartoons or particular generations of console gamers. The feeling is not a modern phenomenon either, it was already familiar to American photographer Ansel Adams: “As I look back to earlier days, there were so few travellers in the Sierra that I began to feel a certain sense of ‘ownership’ they were my mountains and streams, and intruders were suspect.”

One aspect of videogames is that they’re often solitary experiences, in which you traverse a world and grow familiar with its geography and logic. Although these game worlds are often populated by characters, perhaps the limitations of AI keep players from seeing them as alive, maintaining the idea of seclusion. Even if the player is interacting with NPCs, they are still alone in this world, and this is what develops the sense of ownership, a kind of private intimacy.

In our modern age, there’s often a backlash of some sort against game developers who force online functions into their game. EA’s announcement that they would no longer consider developing a game without online functionality in particular drew some ire. Online play is perhaps a feature that threatens this solitary intimacy that a player develops with the game as it either directly brings other people into their world, or exposes the player and their world to others – as in the Walking Dead series, which shares player data across the wider community.

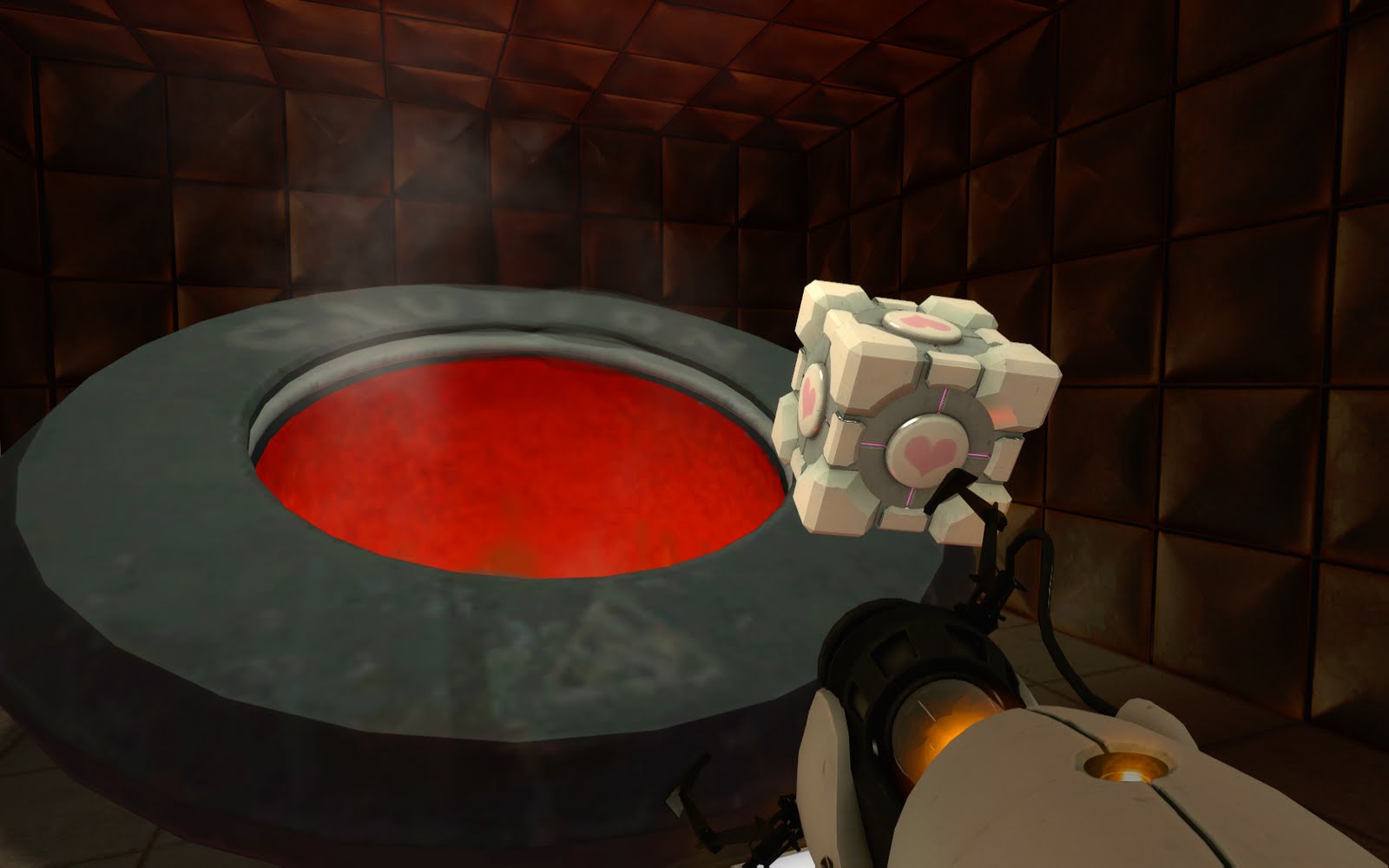

Like a Russian matryoshka doll, this teddy bear effect can be nested as objects within the game world take a role similar to the game itself. A generic NPC following and supporting you might trigger protective feelings, assuming they can be killed or left behind. If a game attributes NPCs or objects to you, and then creates a threat that can take these away, it creates the desire to protect them. The Companion Cube from Portal is a well-known example.

But the key points for surrogates, whether they’re an in-game asset or the game itself, are familiarity and stability. Even procedural games never change their rules, and the relationship between the player and the game world, which itself follows recognizable algorithms. When these face outside threats, it creates the same protective impulse. That’s why you’ll see people vehemently defend a video game on a forum or players going out of their way to try and keep a supporting NPC alive.

Videogames are a strong realization of this teddy bear effect. They are static environments that can be duplicated and distributed en-masse, creating both solitary and collective feelings of ownership for the people who invest in them.

Stewart Melville teaches Literature undergrads at Strathclyde University and writes hack articles for Elance though he’d prefer to just work on his Streets of Rage highscore instead.