Citizen Bane

Joe Köller on videogames’ favorite nonsensical yardstick.

Videogames seem obsessed with the idea of age. Their creators and coverage are both concerned with novelty and hyping up the next big thing to equal and sometimes worrying degrees. At the same time, their not so distant past has come to be worshipped through retro remakes, demakes and iconography. This tendency towards nostalgia is especially interesting considering various and frequent attempts to define the medium through its lack of history.

Ours is a medium in its infancy, to hear pundits tell it. Or maybe you prefer to talk of youth or adolescence, at any rate the consensus seems to be that videogames are not quite there yet, not quite of age, not quite ready to be put on the pantheon of art, culture and social recognition – next to literature and film. And it’s true: Next to moving picture and written word, we are and always will be the new kids on the block. But maybe at over 50 years since their inception and around 30 years as a commercial industry, it’s time to stop claiming youthful innocence and realize that videogames have achieved all the things we wanted for them, and more. We just haven’t been paying attention, because we were too busy demanding recognition.

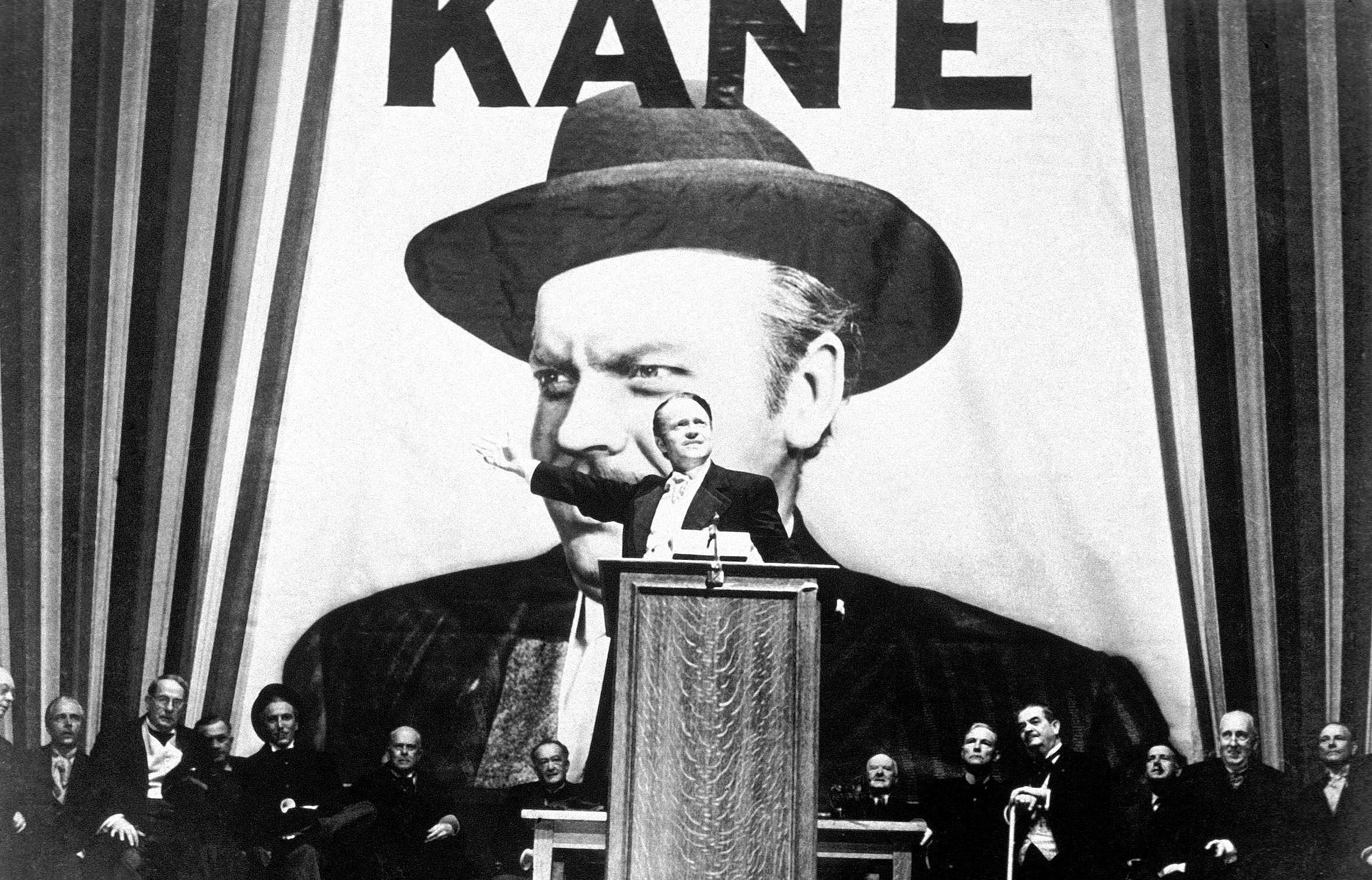

One of the most commonly proposed litmus tests for being allowed to enter the realm of high culture is the creation of a “Citizen Kane of videogames.” The phrase betrays so many misunderstandings and ill-conceived ideas that I can barely begin to unpack a few of them in this article, and yet it has become a shockingly common thing for critics to demand or opine on. There’s a wonderful dedicated Tumblr chronicling the latest round of Kane comparisons that followed Bioshock Infinite and The Last of Us, but it barely offers a snapshot of the trend. Even our own Ethan Woods summoned that specter – not to be confused with the Spector you might expect from him – not so long ago in Issue 1.

Let’s start by talking about the actual Citizen Kane for once, the movie and not the gold-encrusted vision lodged in the common conscience. The film the late Roger Ebert described as both the greatest film ever made and his favorite film. The film Swedish director Ingmar Bergman once called “a total bore”, and its creator “infinitely overrated”. Though perhaps it’s a subject I should leave to our resident movie critic Andrew Huntly. I cannot claim to know much about the history of film, and my knowledge of Citizen Kane’s significance is based more on hearsay than rapt, repeat viewing – something about innovation in areas of cinematography, complex sound and deep focus, which, in combination with it being one of the earliest nonlinear movies, supposedly helped shaped the visual language of film for years and decades to come.

I suspect that this relative helplessness in the face of its technical excellence and significance actually puts me on equal footing with many of the critics who demand a Citizen Kane of games. As I said, it is remembered as an icon more so than an actual movie and, in my experience, you rarely find somebody who has actually watched the whole thing, even among film students. For now, I am less interested in what it has done to earn such reverence than I am in how it achieved that status.

I suspect that this relative helplessness in the face of its technical excellence and significance actually puts me on equal footing with many of the critics who demand a Citizen Kane of games. As I said, it is remembered as an icon more so than an actual movie and, in my experience, you rarely find somebody who has actually watched the whole thing, even among film students. For now, I am less interested in what it has done to earn such reverence than I am in how it achieved that status.

Today, the notion that Citizen Kane is the greatest film ever made, the piece of cinema that legitimized the art form and unified its language, is pervasive to the point of being a commonly accepted truth. But developments of art history, the assertive judgement of significance and context, only ever appear obvious in hindsight. The film opened to crowded halls and positive reviews. Despite nine nominations, it was largely eschewed at an Oscar vote mired in controversy surrounding the wrath and threats of William Randolph Hearst over serving as the inspiration for (parts of) the titular character, but it could generally be described to have been well received.

However, apart from the superlatives critics so like to throw around, there was no real indication that it had made lasting impact. When it arrived in Europe a few years later, the likes of André Bazin, François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard showered it with praise and attention. Only Bazin & co are infamous for their attempts to legitimize film through verbose essays and strong, if slightly unreasonable rhetoric. They are responsible, among other things, for auteur theory, the view that a director is to their film as an author is to their book, the sole creator realizing an immaculate, personal vision. The theory was built to dismantle claims that film could never be art because of its collaborative nature, and honestly doesn’t hold a whole lot of water. Or it certainly isn’t as universally applicable as once proposed. People making strange claims because they worry about the status and acceptance of a new medium, stop me if any of this sounds familiar.

The British magazine Sight & Sound has been polling movie critics for a top ten list of best films once a decade since 1952. Citizen Kane held the top spot from 1962 to 2012, when it was dethroned by Vertigo, but was only a runner-up in the first poll, which crowned Bicycle Thieves king. A poll of critics and filmmakers at Brussels World’s Fair in 1958 named 1925’s Battleship Potemkin the greatest film, but you don’t see people clamoring for the videogame counterpart of that. Citizen Kane came in ninth place on the list.

This brief tour of conflicting opinions is not supposed to slight Citizen Kane’s contribution to film, which I am very poorly equipped to judge, but to point out that it tends to take years and even decades before the importance of a piece of art can be properly put in perspective. And even then we will never reach universal agreement, neither on its merits nor on its significance, as the continuing reception of this supposed best film ever made shows. The idea that widespread cultural and social acceptance can be reached through a single, defining moment rather than a long, uphill battle is ridiculous.

This brief tour of conflicting opinions is not supposed to slight Citizen Kane’s contribution to film, which I am very poorly equipped to judge, but to point out that it tends to take years and even decades before the importance of a piece of art can be properly put in perspective. And even then we will never reach universal agreement, neither on its merits nor on its significance, as the continuing reception of this supposed best film ever made shows. The idea that widespread cultural and social acceptance can be reached through a single, defining moment rather than a long, uphill battle is ridiculous.

Even stranger is the idea that we will instantly know when we have reached that moment. Whether you see it as refining opinions or the beginning of nostalgia, it took Citizen Kane over 20 years to grow on critics. And yet the phrase born from the film is thrown around in launch-day reviews, every time some game proclaims to set new narrative standards in the triple A space. If it’s good, it might be declared the latest in a lineage of Citizen Kanes of videogames. Or it might be found lacking and, regrettably, we’ll have to keep looking. Either option – “It is!” or “It isn’t!” – maintains the myth that we still require such a gift from the gods to properly end the narrative of videogames’ march to legitimacy.

If you do desire such a tipping point, look to the past. If we accept that it is impossible to fully appreciate the significance of any piece of art at the moment of its creation, it stands to reason that our Citizen Kane might have slipped by unnoticed. Maybe it was Zork. Maybe it was Super Mario Bros., or Doom, or Half-Life, or GTA, or Ocarina of Time, or Shadow of the Colossus, or any other of the dozens of games people frequently declare the greatest of all time.

It is twice foolish: first to argue that videogames still require a coming of age moment at this juncture, and then to expect the triple A industry to deliver it. The existence of a videogame blockbuster industry comparable to Hollywood alone should show that the transition to social relevance, and then normalcy, banality, has happened a long time ago. Instead we continue to measure the worth of our entire medium by the output of that bloated beast.

It is twice foolish: first to argue that videogames still require a coming of age moment at this juncture, and then to expect the triple A industry to deliver it. The existence of a videogame blockbuster industry comparable to Hollywood alone should show that the transition to social relevance, and then normalcy, banality, has happened a long time ago. Instead we continue to measure the worth of our entire medium by the output of that bloated beast.

I mock the phrase “Citizen Kane of videogames” not to police other people’s language – familiar as the desire may be for an editor – but because it betrays a certain inferiority complex in critics seemingly still embarrassed by their chosen medium. And that is an understandable reaction, in many ways. But by waiting in rapt silence for the biggest and most risk-averse studios to deliver something new, bold and outrageously well-crafted, we neglect so many other games. Acting as if such titles were a necessity, or even a rarity, for the medium we cover, belittles the work of a scene for which ‘indie’ has become such an ill-fitting umbrella term: a vibrant and diverse group of creators from mid-tier studios to Twine zinesters, whose work is as daring and relevant as any art form could possibly hope for.

Big-name titles make for easy discussion. I can fairly safely assume that a large chunk of my audience will have played or at least heard of the new hotness, and that makes them a good talking point if you want to reach a lot of people. The same desire for universal appeal that brings in this large audience tends to keep them from expressing anything risky or personal, but it can be done, and, regardless of the fact, I maintain that there are worthwhile things to say even of the blandest of military shooters. I understand that there are good reasons to cover these games in detail, and I’m as guilty of it as any other critic, indie cred be damned.

There’s something profoundly cynical about the way many of my peers go about it though. I get demanding more from games, especially the games so big and hyped up they serve as the general representatives of our medium, for good or ill. Asking for our Citizen Kane, that videogames finally learn how to be videogames properly, goes far beyond that, and is frankly insulting to both the form and its most daring creations. Criticize Hollywood all you want, but don’t get it mixed up with all of film. Maybe you shouldn’t spend your entire life getting mad at its shallow creations while slavishly devouring each and every one. Maybe arthouse is more your style. Videogames offer both, and everything in between.

Joe Köller is the current Editor-in-Chief of Haywire Magazine, German correspondent for Critical Distance, and irregular contributor to German sites such as Video Game Tourism, Superlevel, and WASD. You can follow him on Twitter, and support him on Patreon.