The Saturday Club

The following discussion was originally drafted to be part of Issue 1, until it became clear that it was by far too long and too meandering to have any place in there. We decided to keep going anyway and publish it on its own.

Any feedback would be greatly appreciated. We are considering ways to fill the large gaps between individual issues, and discussion pieces such as this are on of our ideas. So please let us know if you enjoyed this, and if not, what we should improve.

Joe Köller: We here at Haywire love games, but we don’t always love the same games. As of late Thirty Flights of Loving, Brendon Chung’s followup to the first person romp Gravity Bone, has proven particularly divisive, inciting the kind of heated discussion most people reserve for blockbuster movies, elections and fast food brands. I’ve decided to drag the back alley brawl out into this public arena, giving us a chance to discuss the merits of Chung’s work in detail and allowing me to harness some of the eloquence previously wasted on backhanded insults exchanged over rounds of Left 4 Dead.

Joining me in this endeavor are our designer Andrew Walt, whose love for Brendon Chung borders on the fetishistic, our contributor Francisco Dominguez, who suspects film techniques detract as much as they add to Thirty Flights of Loving, and our movie columnist Andrew Huntly, who laments the lack of substance in its narrative. I myself enjoy the game when it’s clever, less so when it’s deliberately inscrutable.

While this is not our goal, it’s virtually impossible to discuss a fifteen-minute game and its fifteen-minute predecessor without spoiling parts of their narrative. So before you go on reading, you should take the time to play Gravity Bone (it’s free) and Thirty Flights of Loving (it’s not). I think we can all agree that they are worth seeing at least. Now, Andrew, could you tell us why you mean to marry Gravity Bone?

Andrew Walt: Gravity Bone is, without question, my favorite game. And coming from someone who’s generally pretty conservative when it comes to bandying about superlative adjectives and particularly strong opinions in general, hopefully that opening remark can be read as something more than just trivial gushing.

What I find most striking about Gravity Bone is that it’s genuinely confident without an ironic agenda and that it’s clever without being smug. Here’s a game that exists in its entirety before most games have finished with their installing, loading, updating, opening credits and cutscenes. To achieve this, everything about Gravity Bone has been carefully crafted and deliberately designed. There is no flabbiness, and nothing extraneous or otherwise unnecessary. It’s a succinct, tightly knit game that epitomizes a sort of eloquence of interactive design. I adore that.

I also adore the aesthetic, perhaps at times even more than I do its efficiency of design. The bombastic brass of Xavier Cugat, the Charlie Brown warbling of the game’s black tie formal NPCs, even the slide-whistle soundbite of bringing up your business card. All these little touches are endlessly charming and endearing to me.

As for Thirty Flights of Loving, I’m not quite as smitten with it. I view its strengths as being purely narrative, and it lacks the sustained high of Gravity Bone‘s finale. There is indeed another clever and powerful moment which will prevent me from ever forgetting it, but its exploration is focused more on the structural than the mechanical, which is the inverse of my interests in such games.

Joe Köller: Before we go on to hear what our movie critic has to say about that, I’ve noticed a small issue: You’re both called Andrew and that might lead to some confusion. Doesn’t one of you have an embarrassing middle name we could abuse?

Andrew Huntly: Well my middle name’s Ian if you think that’s appropriately embarrassing.

Joe Köller: And yours Mr. Walt?

Andrew Walt: Danger.

Joe Köller: Sounds legit. Alright, I think I’m just going to call you Milton and our film critic now goes by the lovely name of Steve. Go right on Steve.

Steve Huntly: To my mind, both Gravity Bone and its sequel Thirty Flights of Loving are interesting conceptual pieces. They capture a unique and vibrant art style and a strange sense of subdued awe within that art style. Apart from that, there’s very little about the games that I find involving. Gravity Bone is a neat proof of concept, albeit one sporting mechanics for no other reason than to give the player something to do. Thirty Flights of Loving expands on the aesthetics and ideas with a more scripted ride, and strangely turns out to be the less conventional experience of the two.

The sticking point with both games is that they’re narratively defunct. There’s a difference between minimalist storytelling and simply not giving context and information to the player. This is more forgivable in Gravity Bone – the notion that the game carries any kind of genuine story element seems a little overboard, aside from the ending montage – but Thirty Flights is certainly going for a more story-focused experience, stripping away what little mechanical distractions Gravity Bone had and focusing solely on a point A to point B adventure. Failing to back it up with a substantial narrative is a major flaw for me.

The games are tightly woven and move at an appropriate pace, but there’s just no detail. Thirty Flights uses an awkward, if intriguing quick cut mechanic, but in doing so it favors pace over any kind of exploration of its storytelling ambitions. The limited amount of resources given to the player to piece things together are either too obtuse or plain non-descriptive, resulting in a game with definite storytelling chops, but no story to tell. Gravity Bone‘s ending would likely have had more impact had I felt there was something there for me to grasp onto, and I felt the same about Thirty Flights of Loving. The games favor speed and scripted events over genuine depth and a palpable narrative golden thread, which leaves me rather cold, even if I appreciate their technical competence.

Joe Köller: I agree with Steve on Gravity Bone‘s reticent nature. Milton seems convinced the game proves you can use exposition and dialogue sparsely and still deliver an enthralling narrative, but what narrative would that be? I never seem to find anything in there that doesn’t require excessive speculation on my part. I respect a game’s audacity to make me connect dots myself, but the only way to even take a guess at the significance of the events in Gravity Bone is to extrapolate wildly in any direction.

There’s a section pretty far into Prince of Persia: Sands of Time that involves descending a seemingly endless spiral staircase as part of a dream sequence. I have beaten that game several times, so by now I know damn well you only have to press on and will eventually reach the end, and yet every time I play that segment I begin to doubt myself, begin to wonder if the game is playing tricks on me with an endless loop of stairs. I don’t just get these thoughts because the winding stairs are an adequate visual metaphor for Sisyphean efforts, but also because the game has just previously shown me the consequences of mindlessly rushing forward. You can spend a lot of time hunting for metaphors in Gravity Bone, but with no consistent narrative to anchor them in you can never be sure which are just giant leaps on your part.

On the other hand, I do feel that Thirty Flights strikes a nice balance with its plot. I certainly don’t know all the details of its heist story, but the game has given me enough to sketch a rough outline and it has been pretty satisfying to piece that much together. What do you think Francisco?

Francisco Dominguez: I’d say Thirty Flights supplies enough information to construct the semblance of a coherent narrative sequence in the player’s head. I like this approach, it lets me feel smart when the game allows me to make my own connections. My mechanical engagement with the game may be minimal, but the imaginative engagement it demands compensates, to a point.

I respect Chung’s experimental series in the same way I respect something as chaotic as Jackson Pollock’s work. Thematic and narrative ambiguity make it hard to find meaning in them, but they can also elicit strong personal reactions. Just look at Milton’s ecstatic burbling, or Robert Yang’s more measured reaction to Gravity Bone: “Every few weeks, I start it up again, and I always notice something new and beautiful. I always find some new significance in it; the ending keeps changing. Sometimes it’s about inevitable mortality. Other times, it’s about doomed love. Yesterday, it was about the value of optimism and perseverance.”

If a piece of media is open to so many powerful responses from a single person, nevermind different players, surely that sufficiently justifies the merit of the approach taken? A designer like Robert Yang, involved in gaming’s experimental fringe movements, may be better prepared to parse the meaning from games like these than most, but is the duty with designers to temper their visions for easier comprehension, or on the players to learn to understand games in a new way?

I should admit that, on a thematic level, I struggle with these games. I like my classical modes of thematic representation, the monologues that directly address the fiction’s concerns, the recurrent motifs that reinforce and develop a carefully calculated method of expression. But it has to be recognized that although disorder and apparent lack of meaning can be both daunting and borderline incomprehensible (just ask any newcomer to postmodernism) meaning can be found there.

Joe Köller: Postmodernism strikes me as a very apt comparison, not just for the games’ playful mix of genres and aesthetic influences or their reverent nods to older media (the newspaper menu, the CD loading screens), but also for their departure from universal meaning. You are right of course, to fully appreciate such a game requires effort on the part of the player, but it’s not necessarily just about being hard to decode, or ‘finding’ meaning. Meaning, in this case, is no innate feature you happen upon, it’s formed during your interaction with the game.

I would even go so far as to say Gravity Bone holds no meaning safe for whatever you bring along. It present an empty, reflecting canvas: when a smart man like Robert Yang looks in, it’s obvious no fool is going to stare back, and the multitude of interpretations he offers are a testament to his own versatile mind. Milton, the classicist and guitarist, sees an ancient drama filled with musical splendor. Call it a personal quirk, or even arrogant distrust in the mental faculties of others, but I feel that people are far too willing to read a personalized narrative into ambiguity. They start gushing with praise, and forget that the striking tale they experienced is their own creation, built from vague hints.

The games certainly deserve praise. It’s their carefully crafted ambiguity that allows for these various interpretations and their immaculate style and technical competence certainly help. To laud their ingenious narrative, however, strikes me as giving them too much credit, or yourself too little. I say this with the utmost respect: I think Gravity Bone is meaningless, and gloriously so. Thirty Flights of Loving is a slightly different matter considering its clear central thread, but interpreting the plot is probably still a matter of speculation. Steve, do you want to pitch in on the matter of postmodernism?

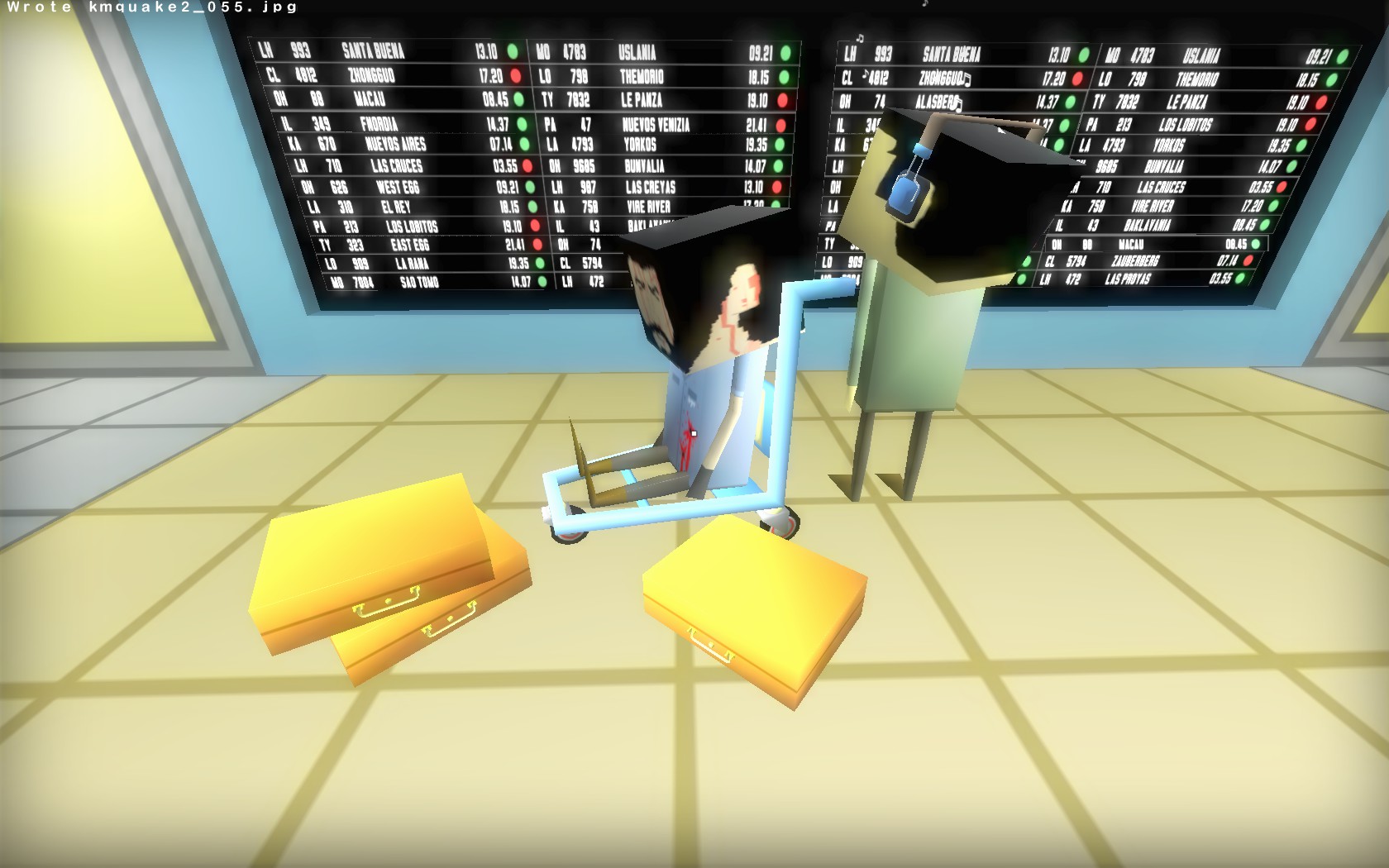

Steve Huntly: The issue with applying postmodernism is that it’s become something of a blanket statement for games that don’t conform to typical mechanical and narrative standards. Games by Suda51 or Hideo Kojima are frequently cited as postmodern, but what does that even imply? Where do you draw the line between being deeply interpretive and being incoherent? Is Thirty Flights of Loving a game about inevitable morality and doomed love, or the joys of pushing your friend around on an airport luggage cart? One option is as valid as the other, and yet they’re so disparate. The aesthetics don’t strike me as particularly postmodern, just kind of neat. There’s no effort to tie it into the overall narrative. The game could be using the same art assets as Doom 3 and it would lose nothing but charm and visual identity. When it comes to the story and the mechanics, it would be the exact same game.

I think the label of postmodernism is an especially strong one, when the games revel more in being hugely open to interpretation with their story than with any kind of thematic resonance. Thirty Flights of Loving comes across as a very elaborate way to tell a simple and undefined story, with little meat beyond the superficial. To me, that frustrating vagueness doesn’t capture a postmodern feeling as much as more detailed games such as Eternal Darkness or Metal Gear Solid 2.

Joe Köller: I think it’s rather telling that you mention ‘frustrating vagueness’ as the exact opposite of postmodernism, even though subjectivity of experience is so central to the concept. To demand absolute certainty strikes me as missing the point somewhat, but then postmodernism is a broad and ill-defined term, and we have a lot more ground to cover.

In my opinion, the visuals of Thirty Flights of Loving add much more to the game than just pleasant looks. And let’s not forget sound design and music. Using conventional graphics, so many parts would have to be removed for sake of consistency: The malfunctioning stairs, the security cameras tied to balloons, all the little outlandish signs and details. It would drastically alter the tone of the game. Milton, I don?t know anyone who loves the aesthetics more than you do, what do you think?

Milton Walt: Aside from the fact that I think I know nothing at all about postmodernism?

Joe Köller: On the role of Thirty Flights‘ visuals.

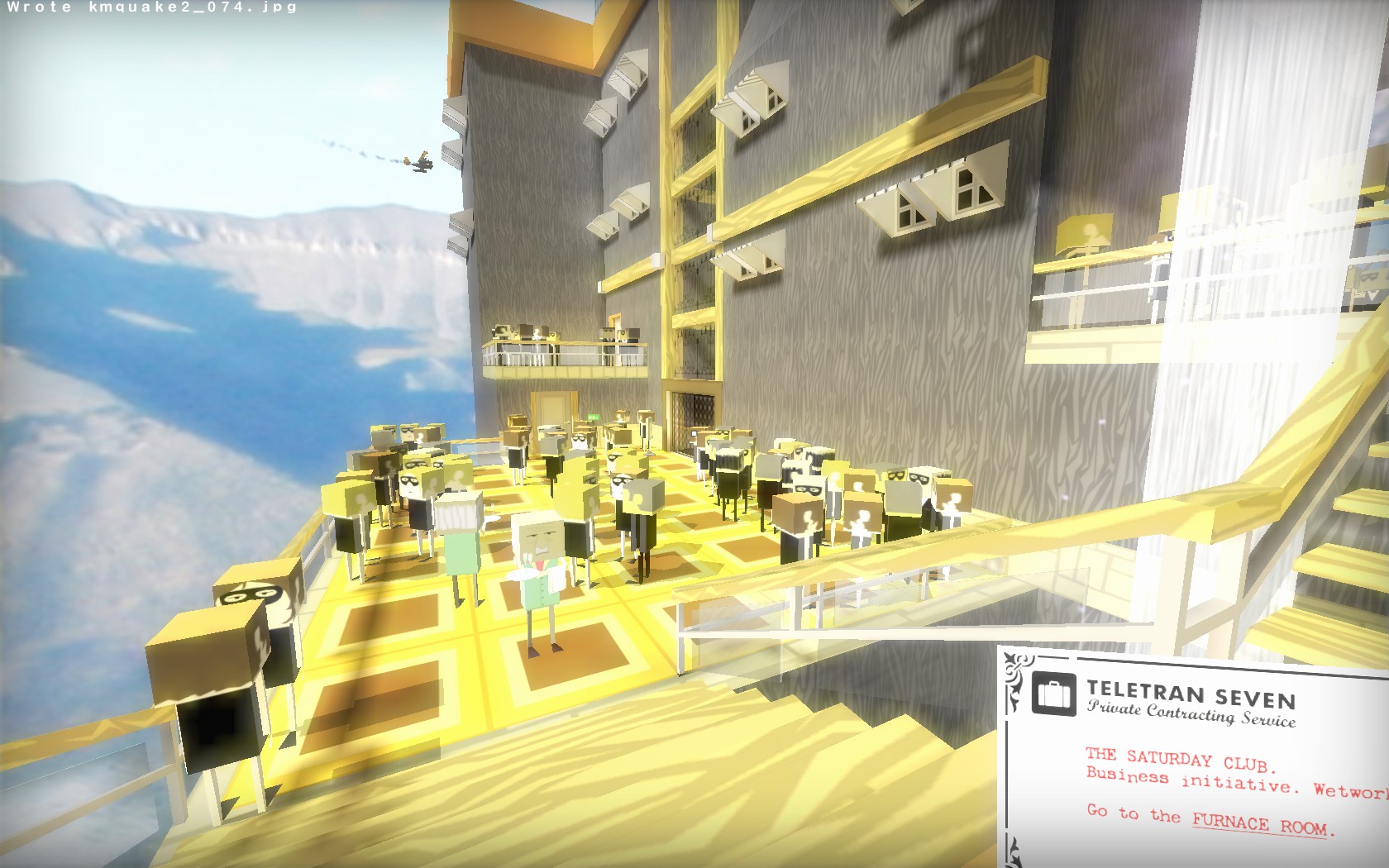

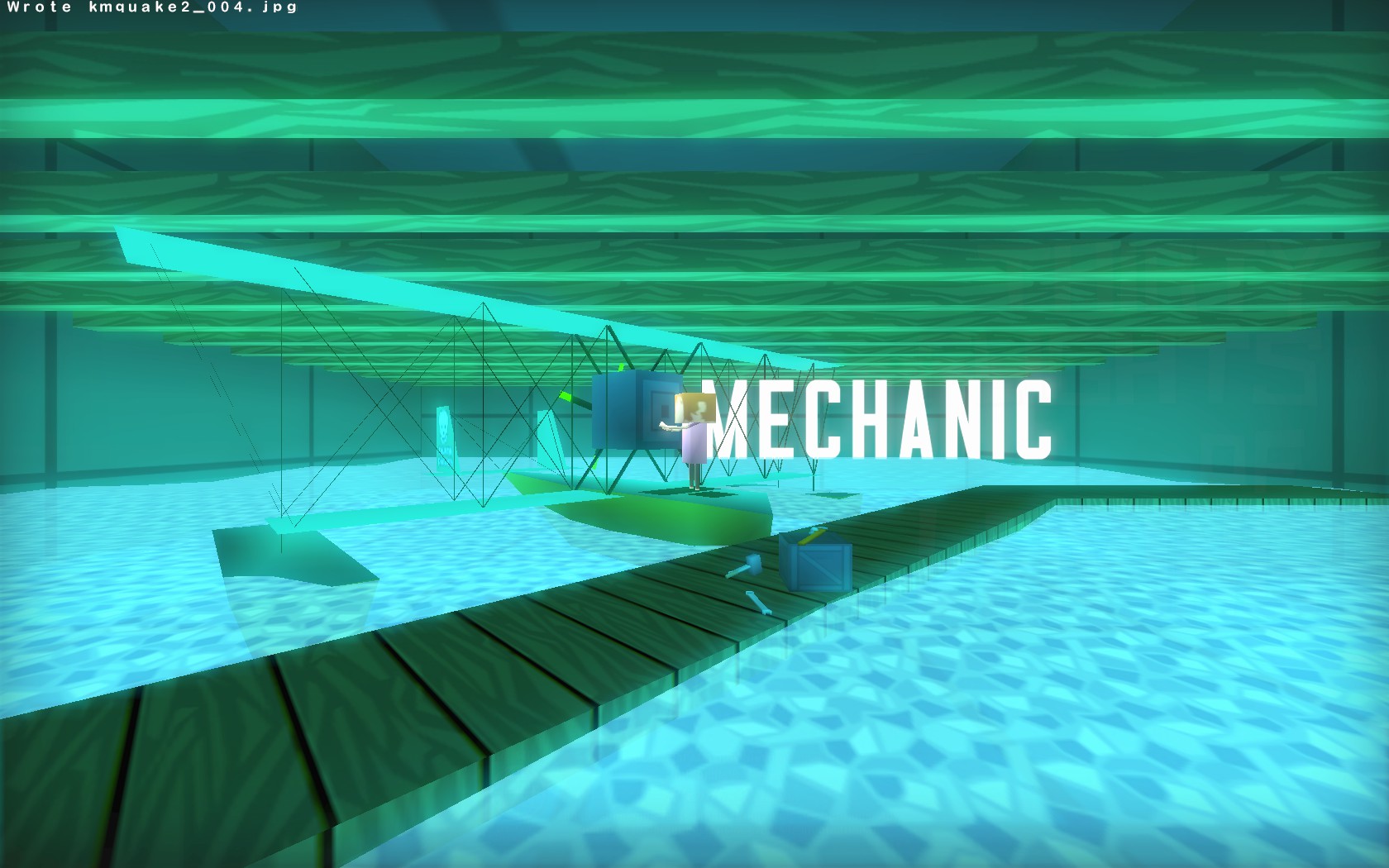

Milton Walt: ‘Clever’ would be my one word summation. One thing that both Thirty Flights of Loving and Gravity Bone excel at is environmental storytelling. The two games manage to present an engaging narrative without any reliance whatsoever on (intelligible) dialogue or text dumps. The sound and set design, and the atmosphere to which they contribute, are far more informative than mere text and dialogue could ever be. Bugging a cocktail glass disguised as a waiter at a black tie affair, taking a plane out of your underground hideout, dashing in a panic through the airport with your injured comrade on a buggy; it’s the environments and actions occurring within them that characterize these sequences, never what’s said (or even worse, what’s read!). I admire that.

I also admire the way in which we’re trusted to form specific impressions of the characters that populate the world. A prime example is the posturing and clothing of the red-haired woman in Gravity Bone. A new approach is attempted in Thirty Flights of Loving with the full immediate characterization of Borges and Anita via flash montage without any voice acting or dialogue crutches.

Joe Köller: Actually, that’s one of the few times the game relies on text to do what mere imagery cannot achieve so quickly and clearly.

Francisco Dominguez: I wouldn’t say the montage sequences ‘rely’ on text. The scenes they’re pictured in are all so explicit that the text becomes a stylish embellishment confirming the obvious.

Joe Köller: It’s easy to call the implications obvious once they’re spelled out for you. Without that anchorage though, how are you to guess Borges’ role at the wedding? How are you to know if Anita is planting explosives, or defusing them?

Milton Walt: Either implies expertise. Don’t be silly now, if a picture says a thousand words, then those characterization montages can fill a couple of decent novellas. The titles merely reinforce the definitions we form based on what we see. They contribute nothing beyond style.

Joe Köller: Assuming that image consumption is such a simple process and will just load a thousand words worth of clear, unambiguous content straight into your brain, then certainly, those montages could be said to be novellas told within seconds. Roland Barthes might have a few things to say about that. Regardless, I wasn’t saying that those scenes would be crippled if not for the use of text. There’s a reason they use it anyway. But you were in the middle of something Milton, sorry.

Milton Walt: Right. Consider the apartment block where the trio attends a wedding ceremony. It conveys a hot and steamy night with ambient city noise, lines of clothes hanging out to dry and the bobbing of paper lanterns and aerial antennae. All of this cultivates a very particular and deliberate atmosphere. The games are effective not because they state outright what’s happening, but precisely because they only suggest. To say Thirty Flights of Loving is narratively defunct is ludicrous, especially when so much of it is embedded in the visuals. Its aesthetic design conveys narrative similarly to how human body language and posture are conversation without words.

Steve Huntly: Narrative and atmosphere are separate things. Thirty Flights is certainly atmospheric, in its quirky little way, but to say there’s storytelling embedded in those square heads and vibrant textures is a stretch. The game’s attempt to express itself solely through visuals is an admirably ambitious goal, however the actual aesthetic scarcely merges with the story. It doesn’t form the characters or give them a place in the plot, nor does it give the locations anything beyond a colourful identity. The image of a bloodied Anita and a beaten Borges stashed inside the airport side room could still be communicated in a myriad of different styles. The inordinate art succeeds in conveying the jarring surrealism of the situation, but adds little to the narrative puzzle.

Francisco Dominguez: I’d like to go back to those montages for a second. The sequences were fun, charming and briskly effective, yet they summarize my main issue with the games: The narrative techniques derive from film inventively, but in ways that deny interactivity, making it a lesser game, and less of a game.

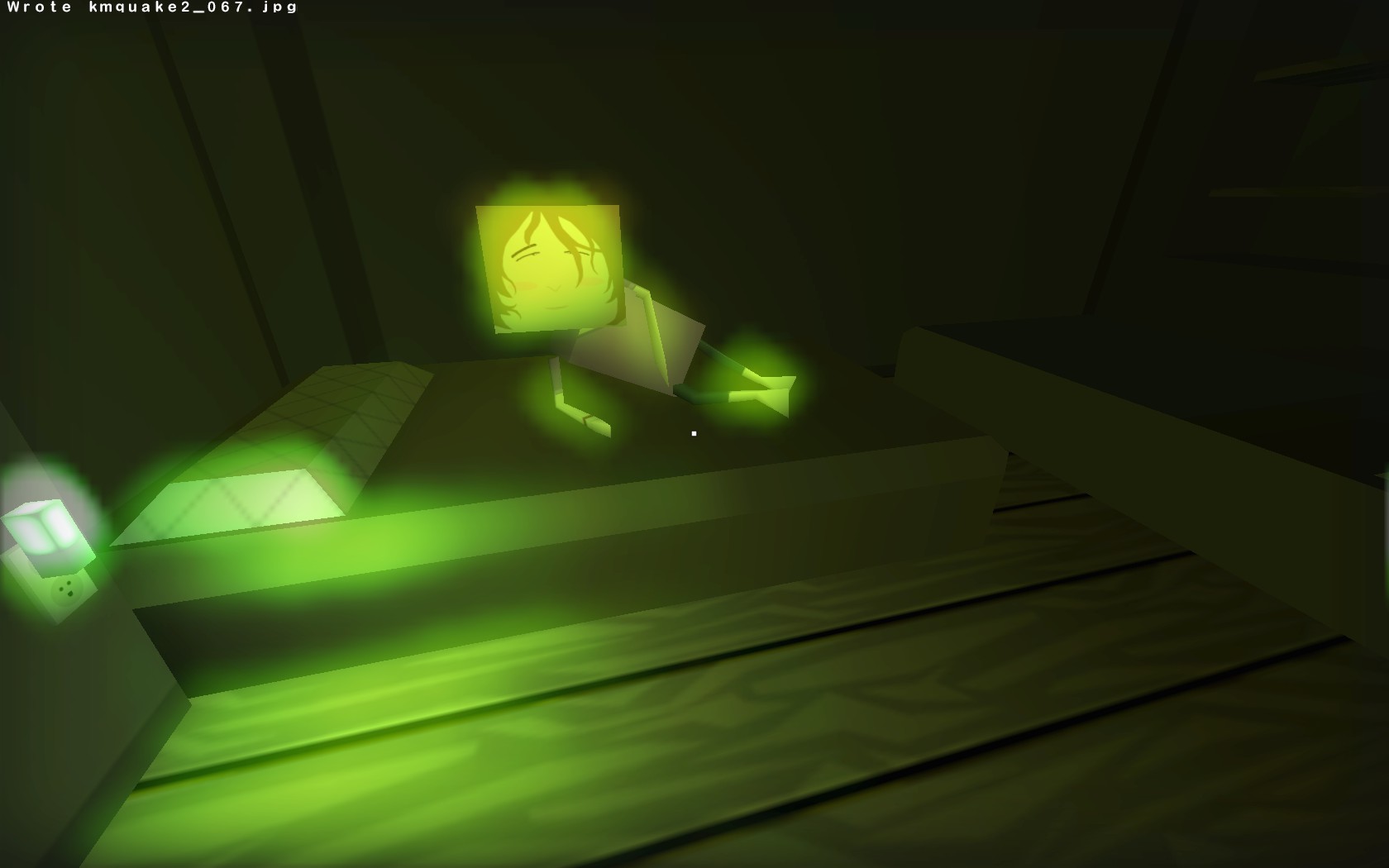

Can you really say that the montage carries the same impact as the scene at the flat when you go to bed with Anita after the party? Yes, that action is the only one available, yet the player is still an active participant in both that action and the ones leading up to it. The staging, the woozily saturated visuals, the expectant silence interrupted only by crickets, every piece making up the stunning, palpable atmosphere of that scene, all of it screamed out the inevitability of what was going to happen. Then you interact with her, only to be dumped back into the game’s Reservoir Dogs disaster through another jarring cut, instigated by yourself.

That’s how I want this information communicated to me. Make me as much a part of these flashbacks as you can, then lurch back to the unrecognizable present with a tragic thud. Of course, this wrecks deliberate pacing, but Chung showed with Gravity Bone‘s final chase scene that pacing and player agency can co-exist. It just remains to be proven if this can be constructed with something beyond a base instinct as motivation. Perhaps I’m being demanding, but that is nearer to my airy ideal execution of the concept.

I’m making a big deal of a single, optional piece of the game. But the presence of filmic conceits elsewhere, the abrupt cuts in Thirty Flights, the imposing intercutting in Gravity Bone‘s constrictive ending, all make me question their application when it forces the player into passive voyeurism.

Steve Huntly: The games do use filmic devices extensively. The old film adage ‘show, don’t tell’ became ‘do, don’t show’ for games, but Thirty Flights is keeping to the former framework. Very rarely do you get an opportunity to really interact with the game. The amount of invisible walls is just staggeringly high. One of the game’s jump cuts transports you to a room with no exits, and only once you place your friend on the luggage cart do the walls behind you magically disappear. It doesn’t make sense. The game is willing to sacrifice logic and coherence just to keep you on a tight leash. It never takes control of your movement or character, but neither does it allow you to move outside of its restrictive boundaries.

There’s certainly something to be said for a game that communicates almost entirely without dialogue, but when it’s replaced by such extreme scripting, is that really a huge improvement? We’re just trading one set of restrictions for another. The way Thirty Flights skims like a pebble across its various scenes and situations doesn’t give me time to settle into the themes and the narrative in any real way. Valve do a far better job at this, keeping you on track while still giving their stories narrative and thematic resonance, alongside some truly engaging characters. I know I keep returning to the lack of detail, but I just don’t see what the brisk pacing achieves when there’s nothing interesting to see.

Milton Walt: We’ve been dancing around filmic devices for a while now, and since you both seem to lament that they are not interactive enough, I’m just going to go ahead and pop the question: Would these pieces – such as they are – work as a film or as any other medium for which you imagine adapting them?

People always seem keen to evaluate and judge the quality of a game (good mechanics, bad mechanics), but seldom does anyone ever seem to explore what it means that it’s actually a game at all. What does it mean that Moonrise Kingdom is a film and not a book? That The Odyssey is a poem and not a novel? That some brilliant works of art often get lost in adaptation? You’ve all said a great deal about its filmic devices, so now imagine that Thirty Flights of Loving is a film. What do you think?

Joe Köller: To be honest, I’m not sure what you’re trying to achieve with this hypothetical conversion. You’ve told me before that you think Gravity Bone challenges established notions of what it means to be a game. Surely this isn’t the extent of your argument, that films can be games too?

Milton Walt: ‘Films can be games too’ is not my argument at all. My argument is closer to ‘narrative-oriented games can be brilliant just by mere virtue of being a game’. A sense of agency, even if it’s as token as controlling perspective in a freefall, can create a powerful moment, even though it’s not exactly a sophisticated gameplay device. Anaphora is not a particularly innovative rhetorical device, the pentatonic scale a melodic device, or Dutch angles a filmic device. Yet their inherent simplicity doesn’t degrade their very existence, least of all when they’re used well.

Francisco Dominguez: The ability to turn your head while every other part of your avatar’s body is locked into a fatal trajectory is not agency. Nor, I would say, is the greater ability to use the gravity gun to fling things at Eli Vance as he speaks in Half Life 2, no matter how striking and childishly amusing it might be. Gravity Bone allows you to create your own significance at this point, but in the most minimally interactive method imaginable.

This continues in Thirty Flights of Loving with the wheelchair shootout. I love the premise of splitting the archetypal FPS protagonist in two, handing the guns to the grievously injured man in the wheelchair while the player is reduced to steering the guy having all the fun, but you cannot influence that scene in any significant way. The second time I played the game, I ignored my keyboard and watched. Borges shot down a number of enemies, then, with a number of enemies still remaining, he fired that slow-motion bullet in some arbitrary direction and the game moved on. My participation was completely unnecessary.

Notions of a ‘win-state’ may conflict with gaming’s tentative aspirations to artistry, but a sequence like this where player agency is not just sternly guided, but entirely fallacious, seems disingenuously contrary to the medium’s strengths. However, I could just be taking the joke the wrong way. And slightly resentful the scene didn’t happen with a shopping trolley in a supermarket.

Milton Walt: If movement and perspective don’t count for agency, then my life is extraordinarily passive and scripted!

Joe Köller: Life also tends to respond to your choices in movement and perspective. Half Life 2 will play out just the same whether you listen attentively or decide to smack Eli repeatedly in the face.

But since you both allude to it, perhaps now would be a good time to talk about Gravity Bone‘s freefall ending sequence. Why do you think the ability to control your perspective lifts it above and beyond regular cutscenes Milton? As Francisco pointed out, Valve has been using this technique for ages.

Milton Walt: Perhaps, but I can’t attest to that. The first Valve title I played was Left 4 Dead 2, which should clearly demonstrate how our different degrees of gaming literacy grant us varying levels of receptiveness to the devices and techniques of the medium. Whether or not a particular element of a game is universally praised only speaks to individual preferences. That Francisco responded apathetically to something I adored only reflects the disparity between how the two of us approach and react to the element, and not its overall quality.

As for why I adore it, that’s a somewhat difficult question to answer. Personally, I don’t recall ever playing a brilliant chase sequence (disqualifying racing games, of course). Escape sequences and timed sequences, sure, but pursuits? Never. Or at least nothing even remotely as well done as Gravity Bone‘s. And again, this reflects confident and intuitive design. How can Brendon Chung be so sure that our first instinct is to give chase? We were just shot and left for dead! But the red-haired woman stole my camera! Do I want it back? Am I in a position to chase her? She just jumped out the window! And why do I hear Aquarela do Brasil? I just have to run!

And of course, there’s the individual moments within that sequence. The near misses, the red-haired woman’s idle cigarette break on the other side of a gate while a train goes past, the glorious dinner party crashing. And then finally the suckerpunch as you’re shot off the catwalk. Yet it’s not the token control of perspective that lets me look up at my assailant or down at my demise that gets me, nor is it the idiosyncratic flashbacks. It’s the music. Perfidia, another Xavier Cugat arrangement. I’m not sure what emotions, if any, it aroused in you, but in addition to being thoroughly mesmerized, I felt betrayed. I felt like we were former or associates or even lovers, that ours was a soured relationship and that I was more to her than a victim of wetwork. There was a genuine stirring for me, which is something that a video game has never before, or since, accomplished. And Gravity Bone does this all without words and certainty, just atmosphere, music, and a maddeningly confident designer pulling the strings.

Joe Köller: Those are very personal reasons for loving it though. It certainly wasn’t my first instinct to chase a gun-toting lady unarmed, for instance. During my initial playthrough I spent a few minutes idly wondering what the game wanted me to do at this point. But of course once I did realize I was meant to give chase, she was still out there, waiting for me.

What you describe might be the ideal response to Gravity Bone, but the results of our, admittedly fairly small, control group show that it’s not exactly the only possible consequence of its design. I like the game, a sentiment now possibly buried under discussions of postmodernism and agency, but if it leaves such a significant portion of our panel confused, frustrated or plain unimpressed, can we really call it eloquent and maddeningly confident?

Steve, what has your experience with that sequence been like?

Steve Huntly: The falling sequence is one of the least unique moments in the whole game for me. From the choice of music to the yellow tinged flashbacks, it combines elements I’ve seen in various other sources of media, from animation to live-action film. The anime series Cowboy Bebop is the most obvious example. Whether it’s a deliberate homage or artistic coincidence, I find it hard to deny the striking similarity between the ending sequence, and a particular scene in Cowboy Bebop. Both involve falling away from a woman in slow motion while the cold and morose past of our protagonists flashes before their eyes at a more natural speed. The idea has been done before with greater context, and the ability to move my head adds nothing of benefit. It can even serve as a distraction, as I stare at the blocky cars below rather than the woman standing above, finding the descent more humorous than pondering.

Milton’s analysis of Perfidia as a song about betrayal does have something tangible behind it, though not for the unique nature of its placement. One of its most famous uses was in Casablanca, certainly a well-regarded movie when it comes to espionage and romance. More recently it found a place in Wong Kar-Wai’s unnamed film trilogy of Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love and 2046 – films whose constant narrative throughline is rejection and love. I suppose we’ll never know how much inspiration Chung has taken from these works, or if he even knows they exist. I still think they’re important to mention in relation to Gravity Bone‘s finale.

Looking at the combination of potential influences here, Gravity Bone‘s finale don’t strike me as unique. It’s a collaboration of well-selected details that I’ve seen and heard before. Details that have, in the past, been used more robustly and with a larger scope. There’s nothing wrong with piecing together art via your influences, Tarantino has made a distinguished career out of it, but it certainly doesn’t fashion an incomparable experience.

So what I’m saying is Gravity Bone is like Cowboy Bebop but worse.

Milton Walt: For me, a creative work doesn’t score or lose points based on how unique it is. A prime example of this would be musicians who issue cover versions of works by older artists. If their cover is better, then well done. I would never say that a superior secondary rendition fails for lack of primacy. I’m not going to pretend to be familiar with Cowboy Bebop, but supposing that I was and recognized Gravity Bone‘s falling sequence as being likely influenced by it directly, I’d be more moderate and view it as a variation or adaptation of particular themes and motifs, rather than as a binary ‘better/worse’ as you have.

Your points also demonstrate how fluency (or lack thereof) within a medium affects perception and interpretation. Suffice it to say, whether or not an experience is incomparable depends on the experiences with which an individual can personally compare it. In my case, I’ve never seen Cowboy Bebop, nor the films of Wong Kar-Wai before playing these games. I even discovered Xavier Cugat thanks to Gravity Bone. Failure on my part to identify these traces should not invalidate my appraisal, nor should success strengthen it. The same applies for any audience.

I was immensely impressed with Gravity Bone for many reasons from gameplay to presentation; so much the better if I found it to be a novel experience, but that’s not what my appraisal hinges on. You were not so taken because you found many connections to other works that diminished your opinion of it. We’re both right. The only issue I take with your approach is how you view its (deliberate?) iteration upon certain elements from certain sources as devaluing. I’m not bothered whether you like it more or less than Cowboy Bebop; what bothers me is notion that “x did this first, therefore y’s rendition is automatically inferior”. Be they theft or tribute, I would’ve thought such touches would enhance the experience for you, not detract from it.

Steve Huntly: I don’t take issue with the repetition of a theme or a motif, but the Cowboy Bebop comparison had little to do with its innovative qualities. It was more that the scene in Gravity Bone lacked the same emotional rush due to the game’s obtuse nature, while Cowboy Bebop provided context and weight. It’s the same with Perfidia in Casablanca and the Wong Kar-Wai films – there’s more narrative and a further development of themes to support the motif. If I were to damn every piece of art that reused a sequence or piece of music I’d have a very limited enjoyment of anything.

Joe Köller: So if this little disagreement is settled, there is another ending we haven’t talked about yet, the museum sequence concluding Thirty Flights of Loving. Francisco, what did you make of that?

Francisco Dominguez: Every single thing I have to say about that feels self-evident. I guess it’s worth bringing up though.

First of all, what a fantastic shift of scene was that? Shattering the climax of the ‘proper’ narrative and turning it into a meditation on what a game is. It may be a self-indulgent practice, and other art forms may integrate it more fully into the main story, but forget the mournful wish to match Welles’ accomplished achievements, this is closer to an artist’s knowing examination of their medium’s tools, nearer to Fellini’s or Paul Auster’s fresh, introspective approach to an established medium than the seismic reconfiguration expected of the prophesied Citizen Kane moment.

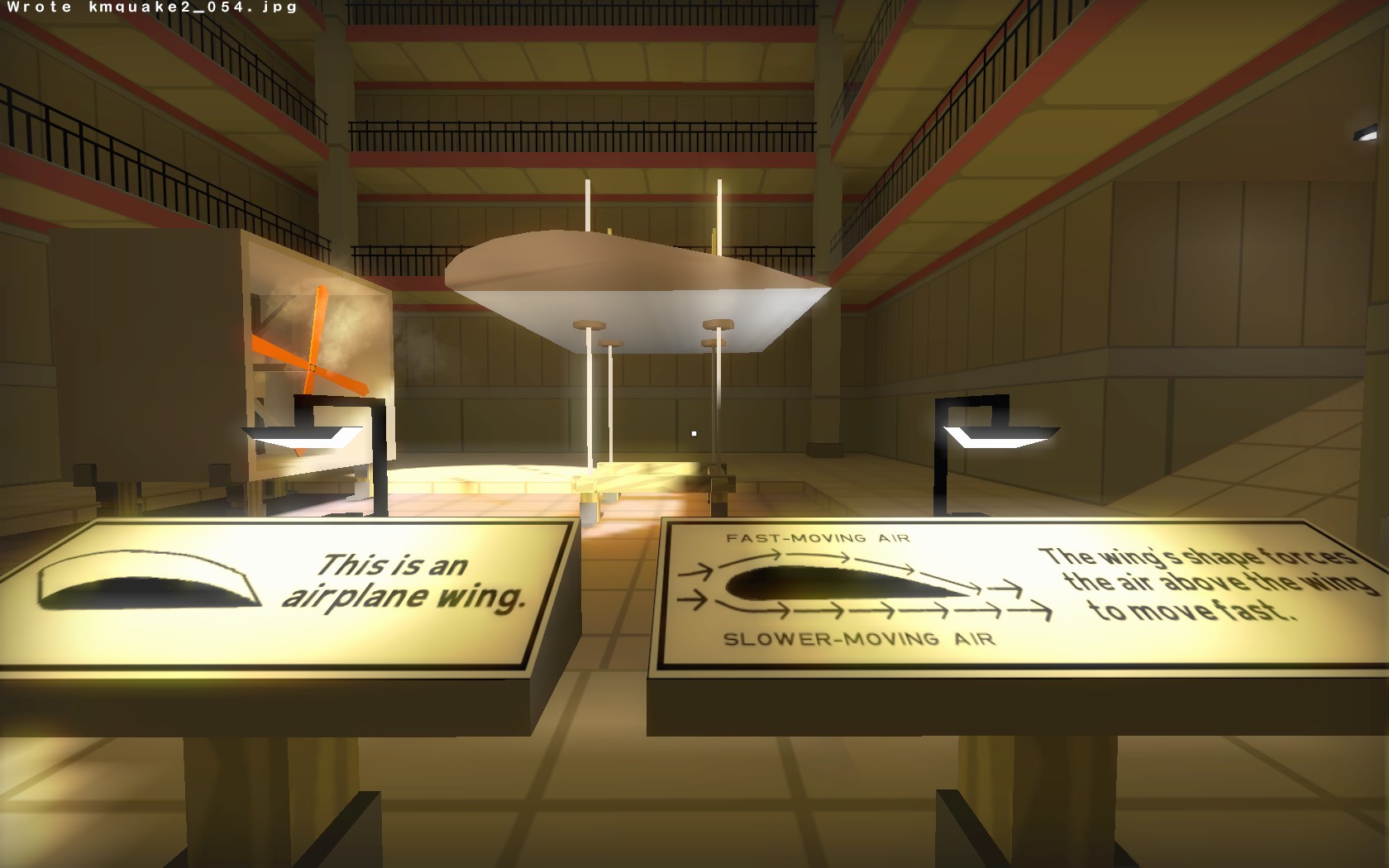

The preceding car crash was intense as it was. But then to burst off the chaotic criminal rollercoaster and tumble into the rarefied air of an art museum? Disorientated, what response is there other than to look around the room, only to see the vehicle of your ambiguous tragedy suspended in the air behind you, the prominent exhibit in a gallery of game assets, fixed to the wall and admired by a cultured crowd of contemplative blockheads.

The preceding car crash was intense as it was. But then to burst off the chaotic criminal rollercoaster and tumble into the rarefied air of an art museum? Disorientated, what response is there other than to look around the room, only to see the vehicle of your ambiguous tragedy suspended in the air behind you, the prominent exhibit in a gallery of game assets, fixed to the wall and admired by a cultured crowd of contemplative blockheads.

The bold and humorous statement here seems to be that, at the very least, the individual components that comprise a game world can be elevated to art, worthy of examination in isolation. The following hall demonstrating the Bernoulli principle goes on to emphasize laws of physics, translated in games into simplified, cogent sequences of cause and effect. A combination of systems to produce an effect instigated by the player. Art and science are contained in different rooms, inert and densely populated for the former, empty and marginally interactive in the latter. Does this say anything for the split in how games are regarded, or even produced? An imbalanced discourse focusing primarily on the aesthetic seems misleading, so, to me, it seemed a commentary on the often stark specializations of game design. There’s a sense of a schism between design and art, an inevitable one which many games overcome, but one that persists in mainstream development. Systems engineers rarely have their artwork featured too. Chung wouldn’t find employment as a mainstream game artist until Tetris gets a 3D remake.

Reckon there’s anything in this as commentary, or are my laughably misguided over-analytic tendencies flaring up again?

Joe Köller: Interesting. I never really considered that angle, and was instead trying to interpret it as another piece of the narrative puzzle, which is perhaps rather telling in your model of art versus mechanics. I suppose the sequence could well be seen as commentary on the different discourses surrounding aesthetics and systems, but then I do share your background in speculative analysis and literature.

Let’s say I entertain the idea for now: Does it raise a valid complaint? It doesn’t seem to me that mechanics and systems find less appreciation (as the empty hallways might imply), just because we talk about them in a different way than aesthetics and narrative. The attendants of whatever fancy event you happen to burst into don’t seem to be engaged in thoughtful contemplation so much as idle appreciation, and I’d argue that gameplay mechanics (exciting gunplay, responsive movement) find the same sort of appreciation, and probably by a much larger crowd of people.

The science portion of the gallery is more interested in explaining underlying principles than illustrating them the way artworks illustrate and express emotion. I think that’s where the comparison breaks down for me, because I don’t think there’s much sense in comparing application to theory. A lecture on art history and color theory would probably not draw as many visitors as a gallery, nor are lectures on physics and laws of motion as popular as their application in, say, roller coasters.

Of course, I am glancing over the fact that thorough contemplation of art and narrative happens both on the side of producers and (informed) consumers, while hardly anyone outside the industry is equipped to talk about design in a meaningful way. Hell, probably most people in the industry aren’t, but that’s another story.

Steve Huntly: I have similar feelings towards the museum section as Francisco, although I took it to mean something different. There’s an air of deliberate snobbery to those examining the displays, as the characters are painted with dour faces and dressed in formal but saturnine outfits, glasses of champagne stuffed into their hands. They all stare at the scattered pieces of art, looking supremely unimpressed by the various game assets.

What I took from this and the ensuing lesson on Bernoulli’s Principle is that the game isn’t something to be broken down and examined piecemeal. The use of the plane wing showed the complete application of the principle, the means to an end if you will. All the pieces of the game are designed to come together to form the experience, and that?s how the game should be viewed. I came away from the museum with the impression Chung didn’t want me to mechanically break the game down in search of an answer. Which is, of course, what we proceeded to do here.

Joe Köller: True enough, and we covered an absurd amount of ground too, but it has been absolutely fascinating to hear your perspectives. Do you have any closing comments you’re dying to get out?

Francisco Dominguez: Yes. I?m dying to get out. It’s been a bewildering and somewhat perplexingly curious conversation, but I’m out of things to say. Thanks for the staggeringly broad conversation, guys, I’ll know what to blame for any future mental illnesses.

Joe Köller: You’re very welcome. Milton?

Milton Walt: Fuck Thirty Flights of Loving, Super Hexagon is the new hotness. Terry Cavanagh 2012! Goodbye!

Francisco Dominguez: Well, that’s one less marriage proposal for Chung this year.

Steve Huntly: I can only say I’m proud of what we accomplished and in particular how it affected Joe’s already failing mental health.

Francisco Dominguez: And providing an economic boost to Austrian whiskey vendors. Next time, their heroin dealers shall profit!

Steve Huntly: I’m hoping we can repeat the same feat next time and begin our crippling of the editorial hierarchy. Then we can reform the magazine to solely produce content Grey Carter dislikes.

Joe Köller: At least then I could say something of note was achieved here. Now, let’s go shoot some zombies.