Games of 2014 (11/15)

Dark Souls 2, Gods Will Be Watching, Hoplite, Shovel Knight, and Luftrausers begin week three of our roundup.

Dark Souls 2

There’s a bit in Dark Souls where the corpse of a dragon springs to life and goes for your throat. There’s a bit in Dark Souls 2 where the skeleton of a dragon springs to life and goes for your throat.

That’s the long and the short of it: Dark Souls 2 is more Dark Souls. Whether this is a good or a bad thing depends deeply on what you want to get out of it. Its combat will be familiar to fans of the series but battle situations have been flipped to favor arguable weaknesses of the player. Level and environment design grows increasingly rote and uninspired in contrast to memorable locations from before. Even side character archetypes repeat like spectres from a past age.

Much of this is accredited to the nature of this as a sequel built to attract readymade fans, and so resembles a sort of soullessness which forms a metatext on the hollowing of creative spirits under the demands of a factory industry. Irony upon irony, whereas Dark Souls was acclaimed for its difficulty, Dark Souls 2 is derided as mean-spirited; critics who adored the first’s textual veneer of nihilism balk at that same aspect now taken proper root structurally. If Dark Souls 2 were a gigantic minigame found within its predecessor – dropped by big hat Logan, perhaps – it would be hailed as a Dark Souls-ified Dark Souls.

Which is not to say life is entirely bleak, rather that it’s a matter of perception. There is still unique joy to be found between the lines, some rare moments when the love that went into its making shines out from its embracing of cosmic dread. I’m sure there are only three other people in the world who care about this, but it was wonderful to come across some authentic Irish voice acting after the nonsense I’ve put up with from BioShock, Red Dead Redemption, The Saboteur, and so on. It’s the little touches: Gilligan pronouncing “west” with an ‘H’ was a videogame highlight of the year for me.

Stephen Beirne was born in August of 1986 and some time later began writing game criticism. You can find his work on Normally Rascal and support him on Patreon.

Gods Will Be Watching

Oh shit. How did I end up here? I’ve taken hostages. The police wants to storm the building, and now they’re losing their nerves and my team is trigger-happy. But we need time to hack the computer. We have to do this, right? For the good cause? At least that’s what they say. A hostage panics, runs away and is shot. I’m shocked. I didn’t want this to happen.

I could have know from movies that taking hostages is not an easy job and often ends badly. Gods Will Be Watching let’s me feel the pressure, however. Morality, emotions and the game’s goals collide brutally. It makes me want to run away, to just end this somehow. To do so, I have to make decisions. But every decision has an effect on everything else. Calm down the hostage or shoot at the police? That would save the hostage’s live or buy more time to do the hack. It’s not possible to do both. Slowly I begin to think less about what might be the right way to finish this, but how to finish it at all. Cold micromanagement begins to annihilate ethics.

The feeling of doing something important quickly fades away in the second act. Now, I’m the hostage that’s being tortured. The game is unfair. I die often and start again and again. I lose every emotional connection to the characters and story by trying merely to get through. Some time later, developer Deconstucteam adds a game mode that removes luck-based difficulty so players can focus on the story. But I’ve given up already. I’ll remember this game for its strong intro.

Benedikt Frank writes for the German videogame bookzine WASD.

Hoplite

The introduction of the Hoplite was a revolution in ancient Greek infantry warfare. Heavily armored with helmets, breast plates, leather and above all a large, round shield, these highly specialized warriors struck terror into their enemies’ hearts with their discliplined formations and advanced battle tactics, involving heavy, long spears and short, deadly swords for the inevitable close quarters melee and the chaos of ancient warfare. Trained to work in a strict battle formation, the phalanx, Hoplite units were known to withstand both infantry and cavalry charges, missiles and prolonged melee in the heat of pitched battle. A fighting unit of Hoplites was a force to be reckoned with.

A single Hoplite, however, was nothing.

And yet, Hoplite pits the player alone against a practically inexhaustible army of demons, the fiends resurrected and strengthened with each level our Greek hero descends further into the underworld. Hoplite is a game of maneuvering and tactics; on each level of the dungeon, a single altar grants a variety of abilities or healing. The procedural nature of the dungeon – a single screen of hexes broken up by pits of lava – means that no two runs offer quite the same skillset and challenges.

The basic offensive options of our warrior are simple: In Hoplite’s turn-based combat, enemies are dispatched with single, swift attacks, either by sidestepping, direct charge or spear-throw. Advanced skills include the ability to recall the spear, pierce through more than one enemy or bash enemies with the shield. All these skills are needed: while demons, coming in four different types, follow a strict and predictable set of rules, they will inevitably overpower the Hoplite if the player is not cautious.

On depth 16, when the levels have become gauntlets of more and more lethal confrontation, the Golden Fleece awaits. And another coice: to teleport back upstairs, to peace and the high-score board, or to continue further down, for even higher scores.

“Hoplite”’s rules may seem simple, its graphics barely more than functional, its challenges modest; but in reality, the deeper dungeons resemble clever mazes of risk and reward, of cold-blooded decisions and careful murder. In a very real sense, Hoplite is the rogue-like equivalent to a chess game’s final moves. Like some of the best games, Hoplite is small, yet admirably self-contained. And like his ancient real-world namesakes, this game’s Hoplite relies on skill and discipline to dominate the battlefield.

Rainer Sigl is a carbon based lifeform mostly based in Vienna, Austria. He has been firing synapses to the tunes of videogames for a very long time.

Shovel Knight

From the first glance at the pixel art and chiptune charms of Shovel Knight, it appears like it came straight out of the ’80s. But actually, nothing could be further from the truth. Old NES games like Battletoads, Zelda II, and Abadox didn’t care if you finished them or not. Games were fiendishly hard – often downright unfair – because there weren’t very many of them, and part of the fun came from beating insurmountable challenges.

Shovel Knight is way better than those games, because it loves you. It wants you to win, and it’s cheering you on with every chunky pixel. Yacht Club Games have a clear understanding of the genre’s heritage, which they often use for pastiche, but also to correct the design sins of the past. It knows when to challenge you, when to drop an unexpected set piece, when to make you laugh.

Like the games of old, you’ll play Shovel Knight over and over again: not because you’ve nothing else to play, but because you’re just really digging it.

Alan Williamson is the Editor-in-Chief of Five out of Ten, blogs at Split Screen, and is a digital factotum for Critical Distance and VideoBrains. He is a self-exiled Northern Irishman living in Oxford, England.

Luftrausers

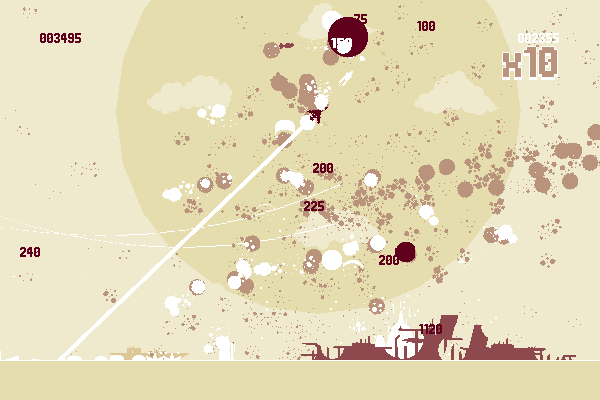

Luftrausers is a simple game. Its most complex element is the different ways to customize your plane through different weapons, bodies and engines. Each component changes the way you play, allowing you to express yourself and find your own playstyle.

At its core however, Luftrausers is a minimalistic score attack shooter. You blast away into the sky and shoot as many enemies as you can until your inevitable demise. While you’re occupied with not getting killed, your ears are being bombarded with one the best videogame soundtracks of 2014. Besides unlocking more parts for your plane, there isn’t much of an overarching goal to Luftrausers. You pick your plane, start the game, shoot at things until you die and repeat the process.

What sets Luftrausers apart from all of its peers is that it constantly makes you feel awesome. No matter how ridiculous the situation, you are always in complete control. You cannot help but feel like a complete badass when you stop your engines and let your plane drop down towards the water only to restart them just before you hit the surface and blast through the enemies that trailed you. Add to this the bombastic soundtrack and you got yourself a game that constantly creates moments that make you feel like an action hero.

Pay attention to its camera movement, the pattern of its screen shakes, the fountains rising from the ocean when you fly close to its surface. Every input in this game has an immediate and powerful impact on the screen. All of Vlambeer’s games show this commitment to action and reaction, but in Luftrausers it is shown in its most distilled form.

Eric Merz thinks it’s a good idea to mix his interests in evolutionary Anthropology with videogames. You can visit his blog, to see how well this is going. He also talks about Videogames on his (German) YouTube channel and has a Twitter account.