Games of 2013 (1/10)

A few of the games we liked last year.

There were a lot of great games in 2013. Far too many, in our opinion, for a list of five or ten, or to declare one our definite champion. Even a list of fifty would not do them justice, but we compiled one anyway. Over the next two weeks we’ll be highlighting five games a day, Monday to Friday. No ranks or numbers, they are all equally close to our hearts.

140

Calling 140 a “music game” might be a little misleading – “musical game” sounds more apt. Where most music games aim for a sense of synesthesia where players feel the beat as they tap buttons and strum plastic guitar strings, 140 seeks to toy with a conflict between sharp, digitally driven rhythm and the analog and flowing world of movement.

In 140 the game world is driven by the beat – it attacks and changes as different instruments play their notes. Platforms teleport from one place to another, safe areas become hostile and jump pads trigger, all to the tune of a lo-fi electronic beat. But the player is decidedly disconnected from that beat, playing a figure that rolls and jumps in an unpunctuated, analog, round and rhythmless way. As such, to play 140 is to struggle to conform. It is, in a lot of ways, a game that systemizes the act of learning how to dance. Players are taught how to take the graceful, sweeping arc of a jump and frame it within a measure of music, or to find the timing necessary to change direction with the beat, despite your momentum. Knowing the rhythm’s beats is key, but it’s not about simply mimicking them – it’s about integrating them into your movement to successfully traverse 140’s challenges.

– Chris Franklin, Errant Signal

Papers, Please

One of my favorite games of all time is Shadow of the Colossus, a game of scale and power that leads the player towards destroying the beautiful and leaving them with an unflinching and potent feeling of guilt. Papers, Please tackles guilt in a different, more grounded way, building an entire game around simple, mundane mechanics but contextualizing them in a radical way. The idea of playing as an immigration inspector, checking passports for discrepancies and ensuring everyone has the correct paperwork, sounds achingly dull. What makes the game is the way it fills itself with interesting characters and sly sips of politics and intrigue.

Papers, Please is set in the fictional country of Arstotzka, a fictional Communist country that has recently reopened its borders. Sitting in your booth, you see people waiting to be reunited with their loved ones, or people wishing to escape awful regimes. All that’s between them and another life is you, and you have a family to keep alive. Let people through or refuse them unlawfully, and you’ll incur a penalty that will be removed from your wages at the end of the day. As the paperwork demanded from residents becomes more ridiculous, the situation only exacerbates, as you try and juggle empathy with the needs of your family.

For a game which gives you the power over the lives of many, Papers, Please leaves you with a distinct feeling of powerlessness. A wife wishes to go through with her husband, but she has the wrong paperwork. You can make the choice to let her through, or you could have already made too many mistakes and can’t afford to lose the credits. It’s a game that makes you feel bad, but not by making you do horrible things, but simply by making you do your job.

Device 6

The brilliant thing about Device 6 is the way it manages to meld overused tropes – seemingly haunted houses, fairy tales, government-funded mind control organizations – into a very beautiful and elegant story that doesn’t feel one bit overwrought. This is in part because of the ingenuity of the design. It invokes both the elegance of delicate prose and the addiction of interaction and touch-based exploration. It takes familiar concepts and puts them at play with each other in a way that decontextualizes them, and in this way makes us experience them anew. Paragraphs shift orientation and defy space in a way traditionally published books have never been able to before. We feel the sprawling mansion, landscapes and corridors as the text elongates, falls and twists upon itself. It successfully mirrors the confusion and uncanny feelings that pervade the narrative without ever feeling like a cheap gimmick. You feel the space because the words act like a map. A map that requires a decoder ring, of course.

The second chapter feels like a modern-day version of Goldilocks written by David Lynch. It manages to weave elements of absurdism and surrealism into the narrative and mechanics so deftly that menacing bears with voice boxes feel natural. And it has what makes absurd works so great: a solid grounding in reality. Living in an age where our own privacy is becoming nonexistent, the idea of our very actions being guided by an outside organization that feeds on our own participation isn’t that far-fetched. Device 6 takes this paranoia and wraps into a beautiful game. It’s not just that its protagonist risks Borg-esque assimilation, but that protagonist and player are actively participating in it. The attempt to escape just leads you further down the path set out for you. Your responses to ingame surveys feed the machine, instead of providing subversive retaliation. Resistance really is futile.

When I first played Device 6 it made me feel like I’ve failed as both a prose writer and a game maker, and this is the highest compliment I can pay anything.

– Kaitlin Tremblay, ThatMonster

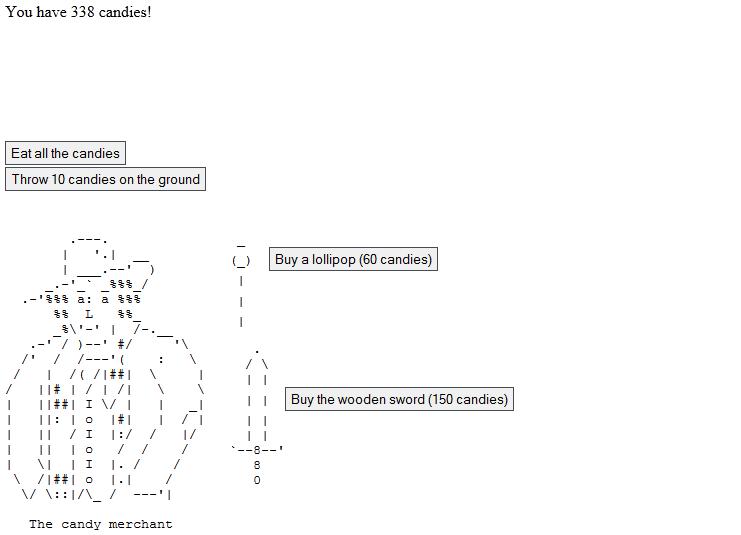

Candy Box

Orteil calls his Candy Box inspired pastry pileup Cookie Clicker an incrementer game, because of its focus on growing numbers, but I don’t think the term really captures what makes these games so unique. Expanding from a simple counter ticking upwards to a dungeon crawler to a puzzle game, Candy Box is a seemingly bottomless well of surprises, presenting an entirely ridiculous, but meticulously interconnected series of events and mechanics. Its content eschews logical progression, its workings make a mockery of convention.

In other games, you might move from fighting one enemy to fighting two or three, half a dozen, then a dozen. That’s the kind of logical escalation we can easily process. Candy Box, however, doesn’t evolve along a linear path. It grows by leaps and bounds. One moment 50,000 candies might sound like a lot, the next you are producing that many per second. Soon the numbers grow too big to make sense of.

Each new discovery in this bundle of joy only makes sense in the specific context of the moment that preceded it and the one that follows it. This makes it both ideal for sharing, and almost impossible to spoil. In Candy Box, you fight a whale, you kill a dragon, you go to hell, you defeat Chuck Norris and, eventually, its creator. From the outside, this is simply a list of bizarre events, but while moving from one to the next, each step promises another wonderful surprise, each transition confounds and dazzles for the sheer change of scope.

Increasing familiarity with their tropes is quickly becoming an issue for games hoping to follow up on the success of Candy Box. Between A Dark Room, Cookie Clicker, Speed Warp and its own sequel, the astonishment of unassuming web pages exploding in your face might soon be spent, and games will have to come up with some new trick. In this lineage, Candy Box will be remembered for its combination of perfect execution and timing. Like a well-told joke, it’s just never as funny the second time.

The Swapper

Mesmerizingly cold and sumptuously dark, The Swapper strands players in an abandoned research station that can be explored metroidvania-style, easily navigable by a network of portals and the generous ease of movement in the game’s kinetic language. But its central mystery of ancient rocks that speak telepathically and a device that can swap minds is not even the feature that resonated the most with me.

Puzzle games rarely offer the freedom of movement on display in The Swapper while still posing challenging and thoughtful puzzles. The simple conceit of cloning yourself and transporting your consciousness allows for an unexpected sense of motion. It takes a while to realize how to move with the help of the Swapper device and come to terms with the opportunities it presents. You can create chain reactions and teleport yourself almost anywhere on screen, or switch to clones far above yourself and climb to higher areas. Puzzles might limit this ability by designating areas where only one thing is possible: teleporting or creating clones. Most of the puzzles come down to planning and careful experimentation rather than skillful execution, although momentum and clever movement are sometimes required to complete the harder riddles near the end of the game.

Lit sparingly, the space station and planet sections stand out in their unique serenity and calm composure. It may come as a surprise that most of its visual design relies on clay models and photographs of everyday items and clutter. Visual cohesion did not suffer as a result: most of these everyday objects create a palpable and realistic science-fiction scenery that is rarely disrupted. A puppet theatre whose strings and seams I did not notice.