2017: The Year of Weird

Some of our medium’s strangest masterpieces: Something Something Soup Something, Caves of Qud, DOTA 2, Cinco Paus and The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of.

Something Something Soup Something

There are two complex themes that Something Something Soup Something addresses: the failed promises of a post-scarcity economy and the arbitrariness of language. Designed by philosopher Stefano Gualeni with the University of Malta’s Institute of Digital Games, the game envisions a fantastical future of teleportation devices and intelligent extraterrestrial life. Teleportation anticipates a post-scarcity world, in which essential goods and raw materials can be made instantaneously available, but the game suggests that the automation of travel merely proliferates labor rather than reducing it. Labor can now be cheaply outsourced to easily manipulated aliens. Thus, new automation technologies and scientific discoveries perpetuate capitalist exploitation rather than unburdening the worker.

Players enact the role of an unskilled laborer receiving portions of soup beamed from alien workers on a teleportation device. Because these underpaid aliens lack the understanding of what defines soup, players must accept or reject these orders based on personal criteria of what constitutes soup. Are rocks served in a coconut with chopsticks any more “soup” than frozen liquid and poison mushrooms served in a hat?

Explicitly drawing from philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, Something Something Soup Something presents us with a semiotic experiment that demonstrates the arbitrariness of language. Like all words, soup is a vague category whose meaning shifts across geographical regions, historical periods, and even among individual people. Are chowders, broths, stocks, stews, and creams categorically soup or distinct altogether? Going further: what constitutes a videogame? While the site claims that Something Something Soup Something can be described as a videogame, the term “interactive thought experiment” is substituted. Indeed, the game provides aspects of what is typically involved in games, such as exploration, stated goals, and the quantification of performance. But what happens if one or more of these criteria is absent? When does something cease to be a game? Is this kind of rote categorization even productive? These are such questions that emerge, all in a game covered by Food & Wine magazine.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.

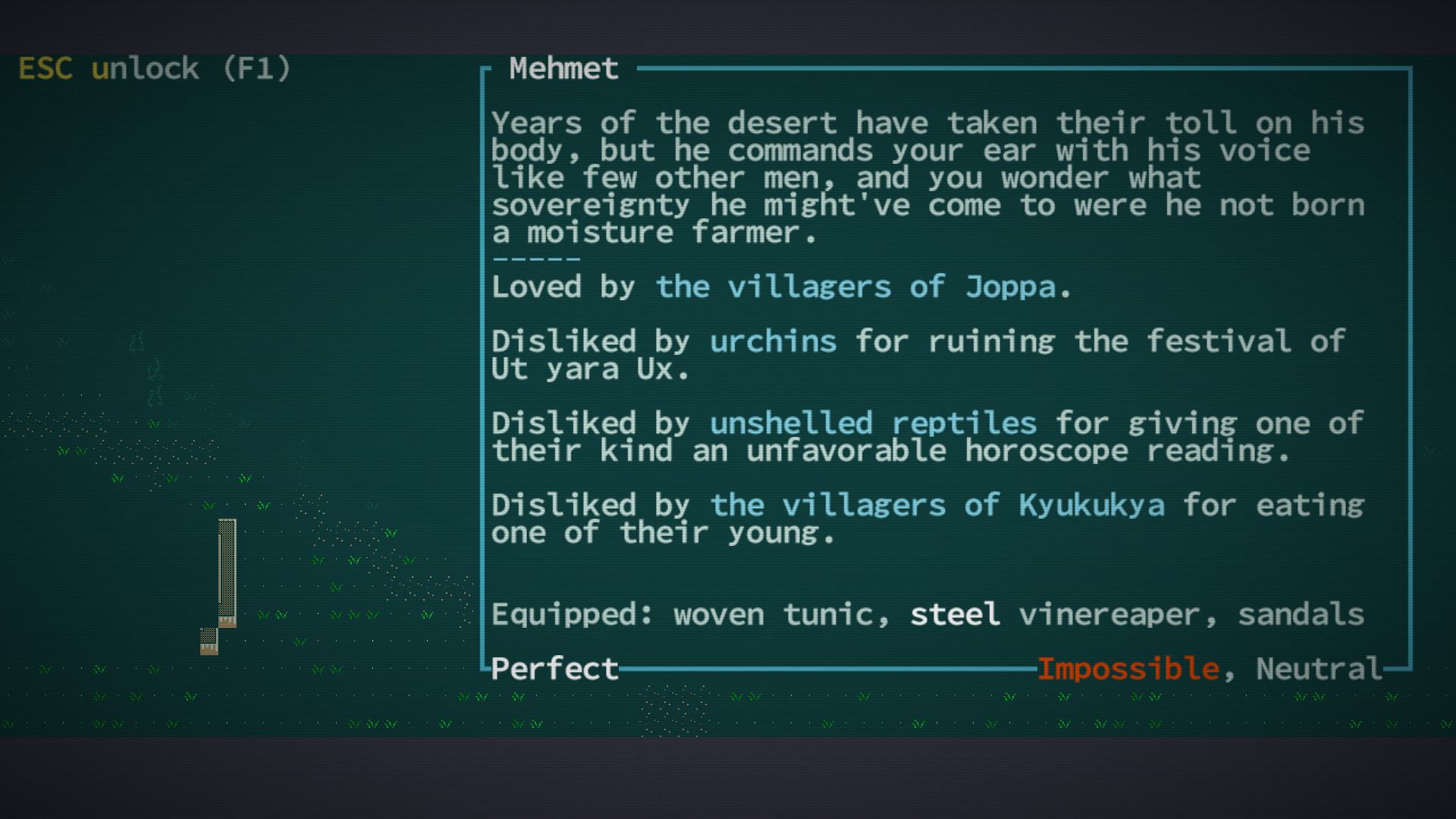

Caves of Qud

Caves of Qud is an ambitious game in a niche of ambitious, even megalomaniacal games. Four decades of roguelikes – “true” roguelikes, not the current hyper-successful flood of roguelike-likes or roguelites, mind – have led to this, a game to be placed along Dwarf Fortress, Cogmind and Ultima Ratio Regum, games which hide their revolutionary approach to procedural generation and narrative experimentation under a traditional ASCII aesthetic and unwieldy interfaces.

Caves of Qud is set in a post-post-apocalyptic world of exotic SF-fantasy; the player is cast into a place of ancient antiquity, with millennia of history buried beneath jungles and salt deserts – think Planescape meets Wasteland, with enough oddities thrown in to fascinate even the most discerning SF-enthusiast. There are hundreds of bizarre combinations in character builds to experiment with; combined with an entirely procedurally generated world and, most importantly, a procedurally fleshed out history of Sultans, cults and distant conflicts, Caves of Qud sets the stage for near endless adventure, even though its main questline stays fixed each time.

Setting forth, for example, as a mutated, randomly teleporting psychic with time-bending powers differs greatly from the adventures of a thick-skinned, gas-farting multi-legged barbarian, whose evil interdimensional twin looms as a constant threat; yet the myriad of different gameplay styles this variety allows isn’t even the main attraction. Instead, Caves of Qud is an eminently literary game, with a quality of text to rival anything else in gaming, and indeed most published genre literature. Poetic descriptions, haunting characters and mind-bogglingly inventive world-building make for a read worthy of the team’s literary patron saint Gene Wolfe. Caves of Qud, with its simple, but admittedly stylish ASCII-inspired tile-based graphics, uses the power of words to immerse us completely, like the best of literature does. A modern classic, not only for fans of the niche.

Rainer Sigl actually played Rogue back in the eighties and is still in love. He writes about games for several, mostly German publications and his own site, videogametourism.at.

DOTA 2

You already know about DOTA 2. It didn’t come out in 2017 and neither did its last milestone update, patch 7.00 from December of 2016. The reason I’m writing about it today is patch 7.07, which brought three things to the game:

- The best iteration so far of the talents they added in 7.00, which made every hero feel partially new, and more importantly, unknown again.

- New items that are bought in the 15-20 minute range. It turns out they aren’t really that great, but the first week or two of the patch had teams building 5 Meteor Hammers, turning team fights on a dime with items nobody has fully internalized yet. It made games be silly fun again.

- They finally let the neutral creeps sleep again at night.

All of this gave me a glimpse of the old 6.53 DOTA from 2008. What I enjoyed a lot about DOTA was discovering hero abilities and items. 7.07 added enough of them at once to be overwhelming again. There’s always new intricacies to learn, but now they added giant mounds of unknown directly to the surface, no need to dig. I love this, but if you aren’t the kind of person who stopped playing due to a lack of surprises, you won’t like the game anymore than you already did. If you are, I hope you’ve already checked it out. The collective’s unfamiliarity is already starting to fade.

Ivo Pačnik never writes and is available on Twitter.

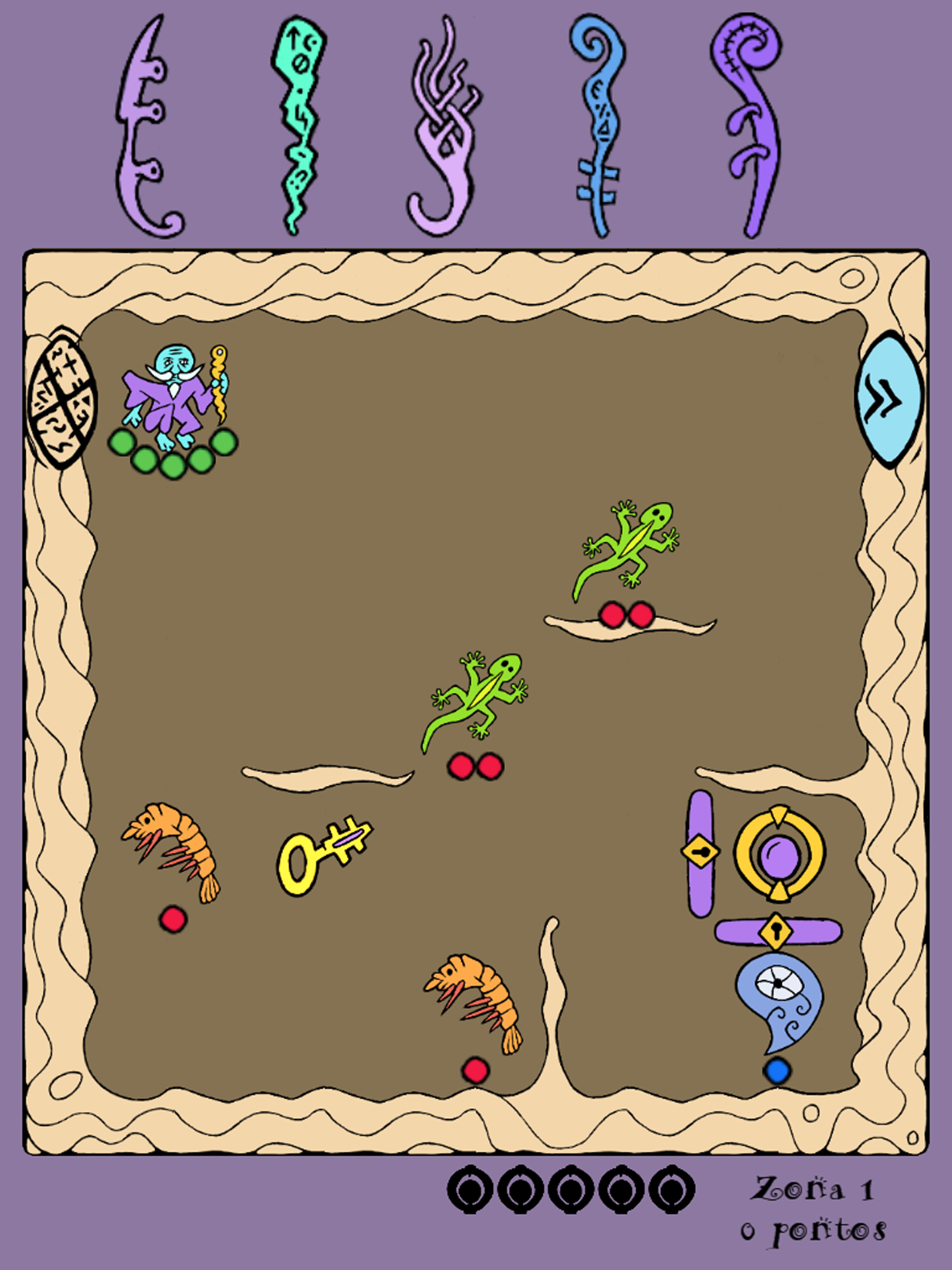

Cinco Paus

There just aren’t enough good games about being a wizard.

If you’ve never played 868-HACK or Imbroglio, you might wonder how a procedural dungeon crawler can thrive on a 5×5 grid. I’m not sure I’m equipped to explain it to you. It’s sorcery. The game feels lean, but never minimal. Every turn counts, but each brings such a breadth of possibility.

The central conceit in Cinco Paus is magic wands. You have five of them, per the title, and their effects are unidentified until you cast them under the right circumstances. Use a wand once, maybe it does nothing. Use the same wand again, when the time is right, and all five of its powers might kick in, dazzling and confusing. These things are very powerful, but unlocking their potential requires cunning, ingenuity, and a little belief in luck – the marks of a good wizard.

Also, all the game’s text is in Portuguese, including the descriptions of each spell’s effect. I don’t speak Portuguese myself, and the effect of this is interesting: these powers must be learned nonverbally, in that other language we access when we play games. The one that feels when things happen, and describes those feelings in memory. Maybe there’s magic there, too?

Joshua Trevett is a freelancer and the managing editor of Haywire Magazine. He mostly likes art when it’s weird, and that goes double for videogames. His writing can be found in publications like ZEAL and The Arcade Review. For secret reasons, it would be best if you followed him on just two out of these three social media sites: Twitter, YouTube, and his blog.

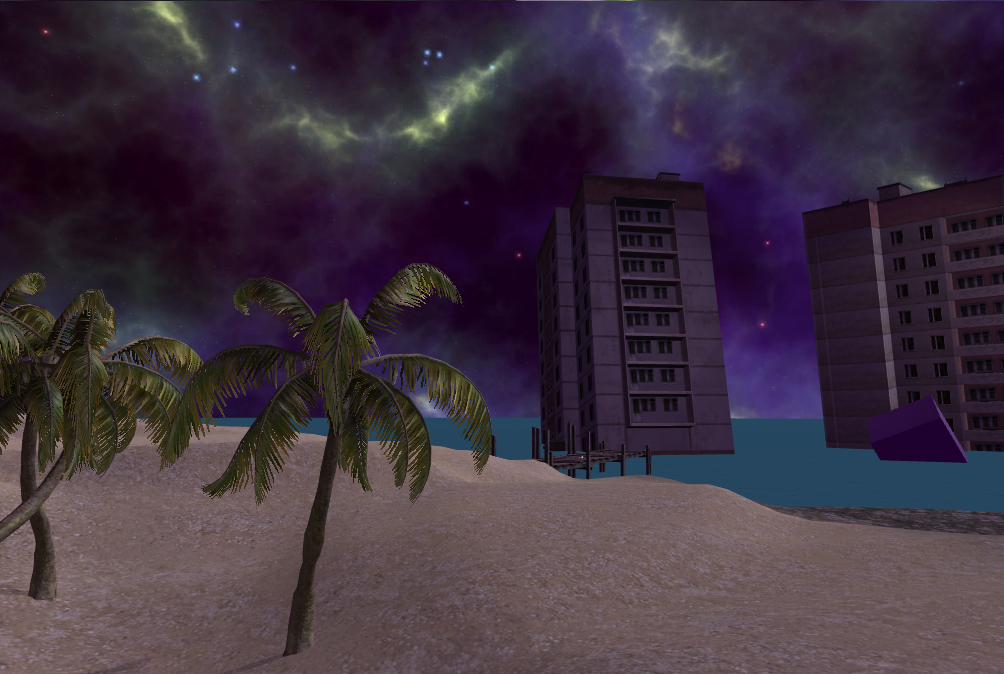

The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of

On its itch.io page, The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of bills itself as a comedic walking simulator. Playing the game, you are told this software is the creation of Dr. Octavius Satterfield, an unhinged academic who promises to help you dream more vividly. Visually, the game is an amateurish mash-up of unpolished terrain, primitive shapes and pilfered 3D models reminiscent of vaporwave album covers. Traversing the patchwork world, Dr. Satterfield will chime in, and reflect on the nature of dreams, the nature of reality, and most amusingly, the nature of interaction with software.

Where other games have simulated software to immerse the player, The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of presents itself as a genuine artifact of early computing. It’s a spoof, a parody of new-ageism from the heady days of early computer software. It’s a mockumentary the likes of which is rare for games, if not literally unprecedented.

More than anything else, The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of is a game that shows a creator who is capable of playing up their strengths, and working within their weaknesses. The game’s interactions are kept simple, its visuals are patchwork, but it glues everything together with writing. It may be a cynical send-up of windbag academic types, but for the player, the experience is pure whimsy.

Spencer Winson is a game developer from Toronto, Canada. He’d really like it if you bought his game Monumental Failure.