2015: The Year of Stuff

Unfortunately we did not find a connecting theme between these games. Anyway, here are Cobra Club, Stick Shift, Toren, Mortal Kombat X, and State of Decay: Year One Survival Edition.

Cobra Club

Cobra Club is the kind of paranoid you can only be in a game about sending anonymous dick pics and then suddenly wondering where those dick pics end up. The dick pic is a curious site for understanding cybersecurity – because Cobra Club exists in a world (idealized, and admittedly so by the creator) in which the sharing of pictures of male genitalia is not the weaponized arm of cyberpatriarchy it is in our reality. To that extent, Cobra Club is utopian, but like all utopias it is tinged with a fascism that lurks behind closed doors.

The male form is celebrated in all of its varying glory, but it is also categorized and collated and passed judgement upon. The female form, in a move as old as utopias, is absent. Cobra Club twists this, however, by confining its utopia; the female is represented, heard but not seen, in the flawed but real external world while the player is caught in the ultimately disintegrating logic of utopianism. Although Yang’s artist statement about this game suggests that he would like to see the dick pic liberated from its current aggressive stance, for me playing Cobra Club was a vicarious revenge upon all of those guys who feel it is their right to deliver their dicks to all and sundry. I also liked playing with the dicks. Cobra Club let me objectify the male body and then discard it. Cobra Club is an ambivalence engine, striking at the heart of male sexuality in the online world.

Amsel von Spreckelsen writes about games at Optional Asides. He has worked for a number of alternative games publications, including The Arcade Review, Memory Insufficient and The Ontological Geek. He lives by the sea.

Stick Shift

With small-scale game producers and art game makers there tends to be position where the critic takes a large collection of works and examines them as a group; following a logic that the exhibition is more important and meaningful than the works within it. This is in some ways understandable, but it runs the risk of denying the individual work to stand on its own. Interestingly, this is a critical stance that The Beginner’s Guide, which I have talked about elsewhere in this series, argues against, and this is one of the reasons I like it so much.

Robert Yang’s sex games feel very much tied together, and are presented as such on his Itch.io storefront, but for me they are worth examining separately and on their own terms. Stick Shift is I think the best game of his that I’ve played. It is self-contained, in the sense that it has an internal language that is consistent. It tells you what it wants you to do and trusts you to do that for it. In doing this it brings the sexual act and the act of gameplay to an accord and expresses the links and commonalities between them.

Stick Shift is a wonderful meditation on the negotiation between player and machine, the mutual trust and care required for the one to manipulate the other into a state of ecstatic and yet momentary continuation, reminding constantly that at the end of every level there is a checkpoint, a victorious moment, in which the sublime flow of action ceases.

It is, of course, as with most tech-sexuality, a very phallocentric and teleological understanding of intimacy, but, in and of itself, that is all that it needs to be.

Amsel von Spreckelsen writes about games at Optional Asides. He has worked for a number of alternative games publications, including The Arcade Review, Memory Insufficient and The Ontological Geek. He lives by the sea.

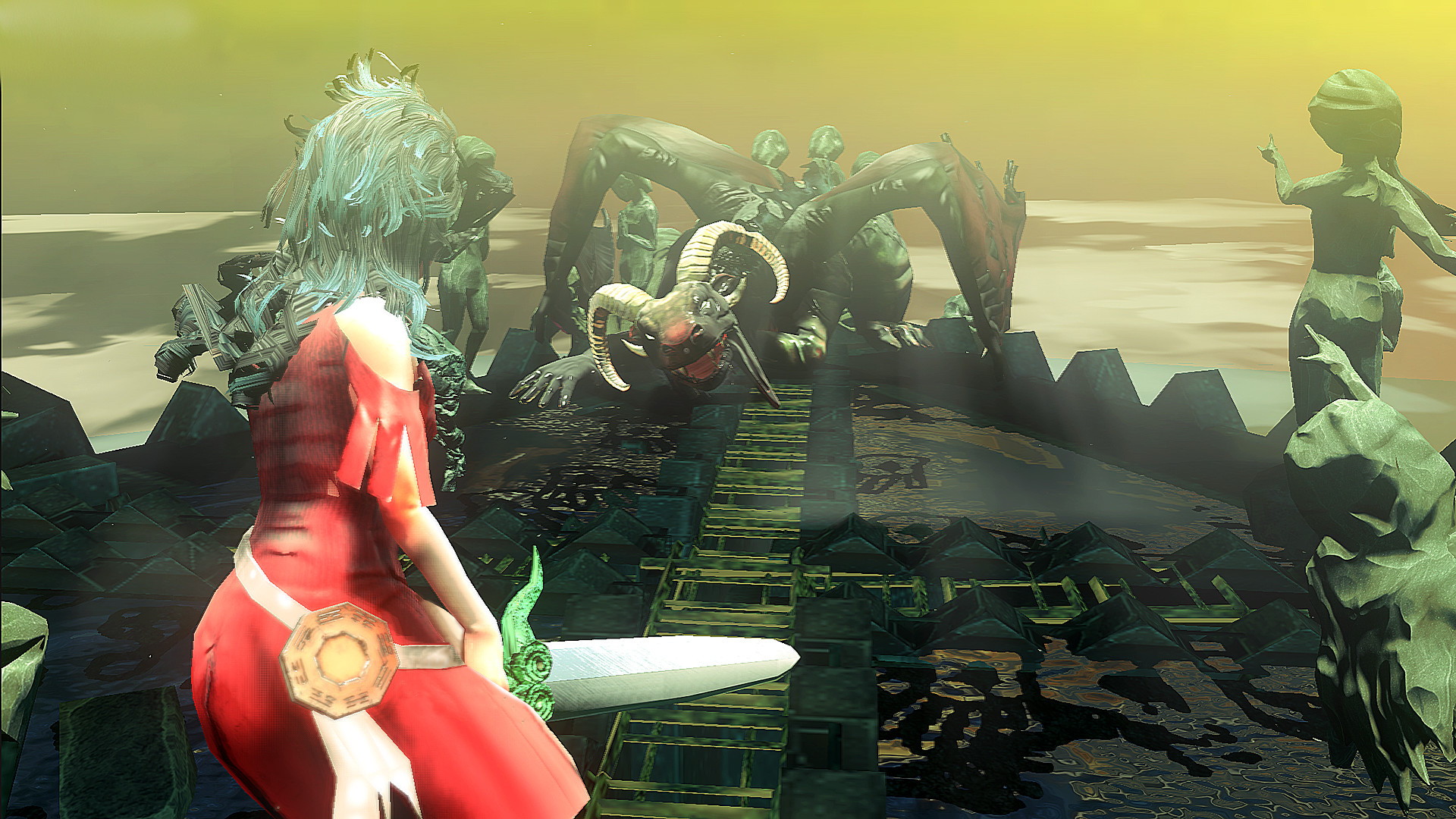

Toren

Few games manage to embody so many emotional and aesthetic extremes in a single moment as Toren. Just the changes in the heroic Moonchild’s walking animation from room to room speak so much to a difference in power, vulnerability, renewal, fear, beauty. Throughout the two-hour playtime the back-and-forth between the Moonchild and the dragon at the top of the world circle back on one another: hunting, battling, dying and returning to the beginning once more.

I seldom get an opportunity to call a game “dense” but I can’t think of any other way to describe Toren. It’s deeply metaphorical, magic-realist, contemporary, personal, philosophical. Toren is the rare game that creates a harmony between play, visuals, writing and motivates its aspects to speak to something.

Toren largely eschews traditional puzzle-solving or combat (although it features basic and functional systems for both) so much as it uses videogame conventions as methods to communicate an idea of the world. In Toren, everything ends and it’s always tragic but apocalypse offers an opportunity to nurture something new: the game is sophisticated in its motivation to say something. It’s a concise and poetic game that somehow slipped under the radar.

Mark Filipowich is the co-coordinator of the Blogs of the Round Table feature at Critical Distance and the curator for Good Games Writing. His worked has appeared in PopMatters, The Border House, The Ontological Geek and many other fine virtual games locales. He has a sweet blog called bigtallwords and he tweets irregularly and irreverently at @thecybersteam.

Mortal Combat X

The story in a fighting game, especially one like Mortal Kombat where the fatalities are a large part of the game and its performative version of physical supremacy, can often be seen to be a bit of an obligation. It is not only that the games are designed to be fast-paced and competitive, bringing opponents back into a match with minimal hesitation, but the sheer number of possible combinations of outcomes involved in any one session of play make the establishment of a consistent narrative almost impossible to tie down ingame. And yet, the sheer oddness of the situations most fighting games explore require often incredibly convoluted parenthetical stories to explain and debrief. Fighting games accrete narrative like a cocoon, while inside the caterpillar liquefies itself into a mass of possibilities and violent conflict.

I’m not a huge fan of fighting games; I find online interactions in games invariably unsatisfying and with my local friends I prefer to play boardgames for that friendly competition. But, on the other hand, I really enjoy hitting a guy in the face on a computer screen while more blood than could possibly be in him splashes onto the floor between us. I also love a good soap opera, full of shocking reveals, smouldering looks between rivals, and callbacks to things that happened years ago. Mortal Kombat’s story mode is perfect for that.

Amsel von Spreckelsen writes about games at Optional Asides. He has worked for a number of alternative games publications, including The Arcade Review, Memory Insufficient and The Ontological Geek. He lives by the sea.

State of Decay: Year One Survival Edition

There’s a road in the town of Marshall in State of Decay where I sometimes got into scrapes, because it was close to my preferred home base and I’d often take off on foot, the better to preserve my cars. I’d juke my way through an undead horde, or roll away from the rotting, sinewy hands of a feral zombie, careful to avoid the steep cliffs of the river that split the town in half. When the upgraded Year One Survival Edition was released, I found myself on that same road, only now I could see the flames dancing across town around the courthouse. Smoke twisted and curled in the sky above the street. It was such an evocative change, bigger than the flowers and faces and upgraded textures – a change that shifted the game into the more expansive space of disintegrating world – that I stopped and stared in awe. This place that I’d loved so much had become so much more real, so alive, and had still been packed somehow into a 5 GB download on the Xbox One.

I don’t remember precisely when I realized State of Decay was something special. Maybe it was the first time I noticed I was playing as a black man and having a meaningful conversation onscreen with a black woman, or when I got to the non-exaggerated depiction of a former sex worker. Maybe it wasn’t any of this, but instead the inherently feminist setup that required attention to team-building and community, or maybe it was just the sheer joy of wading through zombies while the difficulty ratcheted up in the Breakdown DLC. Maybe I always felt it. Regardless, the expanded edition brought new life to a criminally underrated experience, a fun, funny title easily adapted into whatever kind of game the player wanted. The new release brought not only visual tweaks but mechanical changes as well, and for previous owners, the addition of a new playable character, the first woman of Indian descent I remember ever embodying onscreen. And oh, she was good. So good.

State of Decay should be a tedious experience, all driving, running, and searching on repeat. Playing it a second time should be even worse. But there’s something special about this world, about the little details in the houses, about the building of a team, that makes it hard to leave Trumbull Valley behind. Every moment is important, every step careful, because a mistake means death, and here, that’s permanent. There are no redoes. Once lost, a moment is gone forever, disappearing in the dust settling on a back country road. This apocalypse has the beautiful weight of something real, something worth preserving, and yes, repeating, again and again until it comes out right.

Alisha Karabinus is a PhD student in rhetoric and composition at Purdue University, focusing on games studies and digital identity. You can find her at Not Your Mama’s Gamer or on Twitter if you’re so inclined.