2015: The Year of Space

We’ve taken to the stars with Elite: Dangerous, Rymdresa, Pulsar: Lost Colony, Galak-Z, Deadnaut, and Duskers.

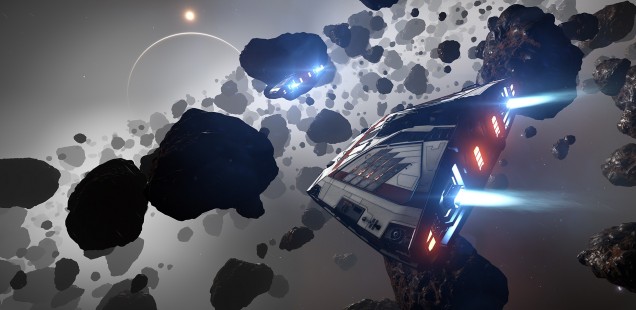

Elite: Dangerous

There are many thousands of inhabited planets in Elite: Dangerous, and each is described by a huge amount of information, covering everything from the planet’s surface temperature and axial tilt to what government is running the show. The mind boggles at the scale of this colonized and corporatized Milky Way, but in this game you play as a person who never leaves the computer screen which doubles as their ship’s cockpit, and all you care about is finding whoever will pay the best for the stuff in your cargo hold.

The bones of this game are remarkably similar to the original Elite. My mother played that when she was a little younger than I am now, and this game shows respect for that history – many of the ships and space stations haven’t changed much from when they were simple vector shapes. In full graphical splendor, it’s easier to notice a bleak undercurrent to the now retrofuturistic setting, where market capitalism has colonized space and the shipyards of a thousand worlds all produce the same trapezoids. There must be some crushing monopoly in power here.

Still, the old buy-low-sell-high formula retains great strength, encouraging you to keep as many plates spinning at once as you can. In 1984, games demanded more from players’ imaginations. It’s both refreshing and oddly reassuring to see the franchise carry that forward. It’s a very slow burner, but it benefits from an age-old robustness; the most rewarding way to play this one is to carve out a habitat, immerse yourself there, and hone your ability to find your own stories.

Joshua Trevett is a freelance writer and editor. He mostly likes art when it’s weird, and that goes double for videogames. That’s how he knows games are art. His writing can be found in publications like ZEAL and The Arcade Review. For secret reasons, it would be best if you followed him on just two out of these three social media sites: Twitter, YouTube, and his blog.

Rymdresa

Although space is a popular setting for games, their relationship is a little tense. Games abhor a vacuum, and it’s commonly agreed that the big old void in the sky must first be filled with something of note to be made interesting, be it thrilling combat, unexplored worlds, shrewd trading, cutthroat diplomacy, sexy aliens, or a combination of all of these. Yet the great nothingness that surrounds us is, in itself, quite something. It’s the perfect environment for a quiet, contemplative experience.

Fortunately, more and more games seem to realize this, and Rymdresa is one of them. Its rendering of space travel is far from flashy: you are presented with a 2d plane, point your ship in the direction you want to go, and try to avoid objects that zoom past around you. You might spend experience points on stat increases or find new gear with names like “Made-Up Engine of Ice Cream” or “Impressive Aura of Potato”, but their impact on your ship’s maneuverability is far less than that of a single asteroid crossing your flight path. With your ability to control events largely frustrated, most of the game boils down to hoping that disaster isn’t waiting for you just out of sight.

Rymdresa uses this mechanical void to focus instead on the poetic musings of your astronaut, and while I am still not entirely certain if I actually enjoy the writing in these, I definitely appreciate a game that realizes that the grandness of space is impressive mainly as a lens through which we examine the smallest, the most personal experiences. You gotta love a game whose idea of a bossfight consists of talking a cosmic superbeing through its emotional issues.

Joe Köller founded Haywire, does German correspondence for Critical Distance, and occasionally writes for German sites such as Video Game Tourism, Superlevel, and WASD. You can follow him on Twitter, and support him on Patreon.

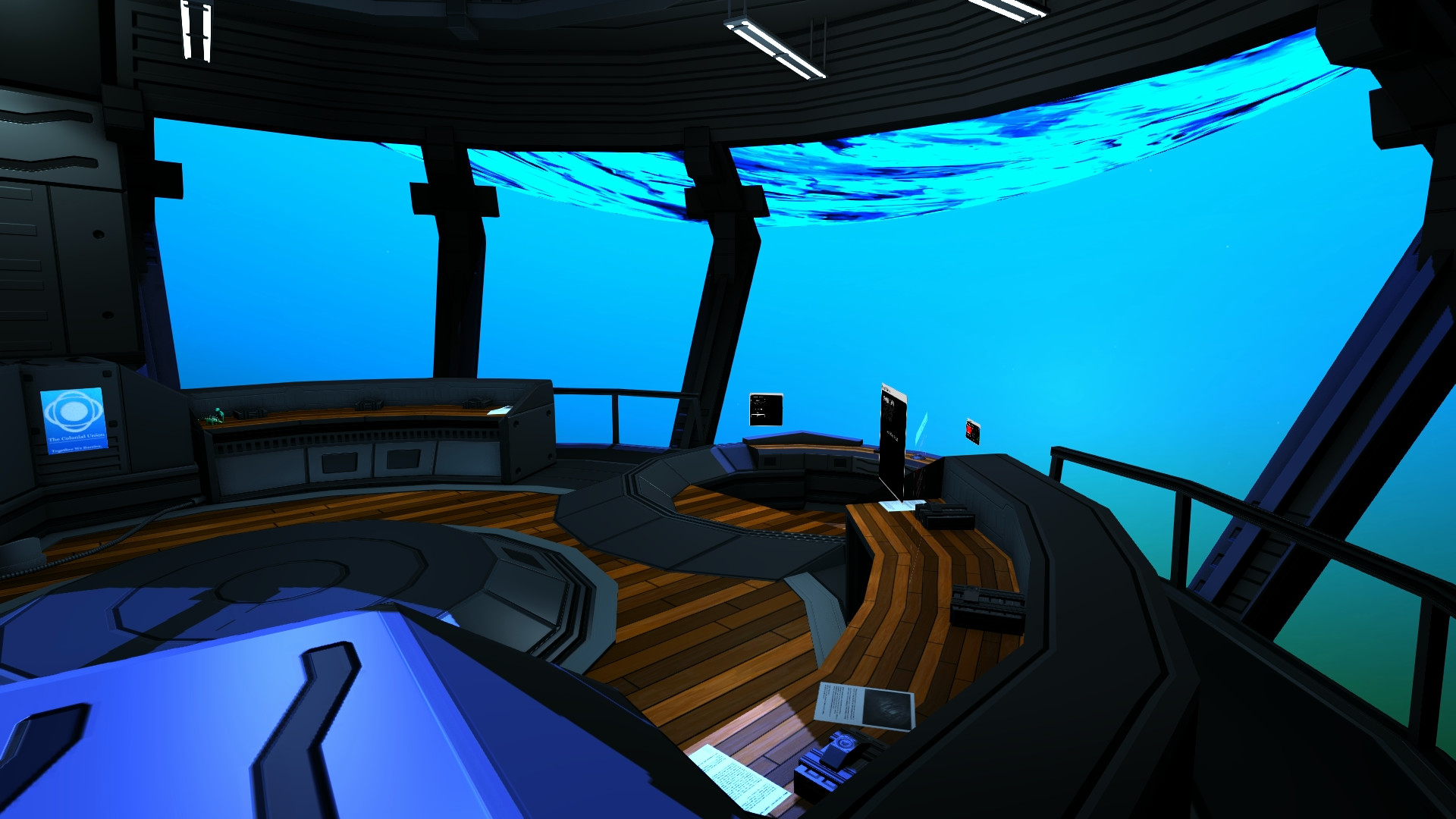

Pulsar: Lost Colony

Artemis is one of those games that makes so much sense that it is surprising it hasn’t been made before. Billed as a Star Trek bridge simulator, players assume the role of engineer, scientist, weapons officer, pilot, communications, or captain aboard a starship. It is truly one of the greatest in-person LAN experiences in all of videogames.

Pulsar: Lost Colony takes that idea and enhances the experience to something more accessible. It comes with built in online play so one could play in the comfort of their own home. While it loses some of the immediacy and atmosphere of local multiplayer, Pulsar is infinitely more accessible and playable. The starship no longer exists as just a series of screens with a third-person view. The starships in Pulsar are fully 3D with passageways, lounges, and rooms. Players are able to control an individual character with their own set of skills with a RPG-like points upgrade system. Furthermore, the player-run crew is able to participate on away missions on a planet’s surface or a derelict starbase. This feature adds a whole new experience that feels full of unlimited potential.

The main attraction is the ship-to-ship combat which emphasizes teamwork above all. Science officers have to stave off computer viruses and modulate shields. Engineers allocate power to the proper systems. The weapons officer can command the most deadly of arsenals. The prospect of exploring different planets, completing missions, and encountering new undiscovered aliens instills Pulsar: Lost Colony with the potential to be a rewarding, unending game to fulfill all your sci-fi impulses.

Unfortunately, Pulsar: Lost Colony is still in early access on Steam. In fact, it is still fairly early in its development. However, the game is currently extremely playable despite not being content complete. After a very satisfying five hour game with a full crew of friends, many of the planets and enemies repeated over and over, but the core game is so satisfying that it is one early access game to watch.

Dan Paredes is a writer for Unique Drops and co-founder of the Infinite Lives Podcast. The first game he ever played was the classic Apple II game, Bruce Lee.

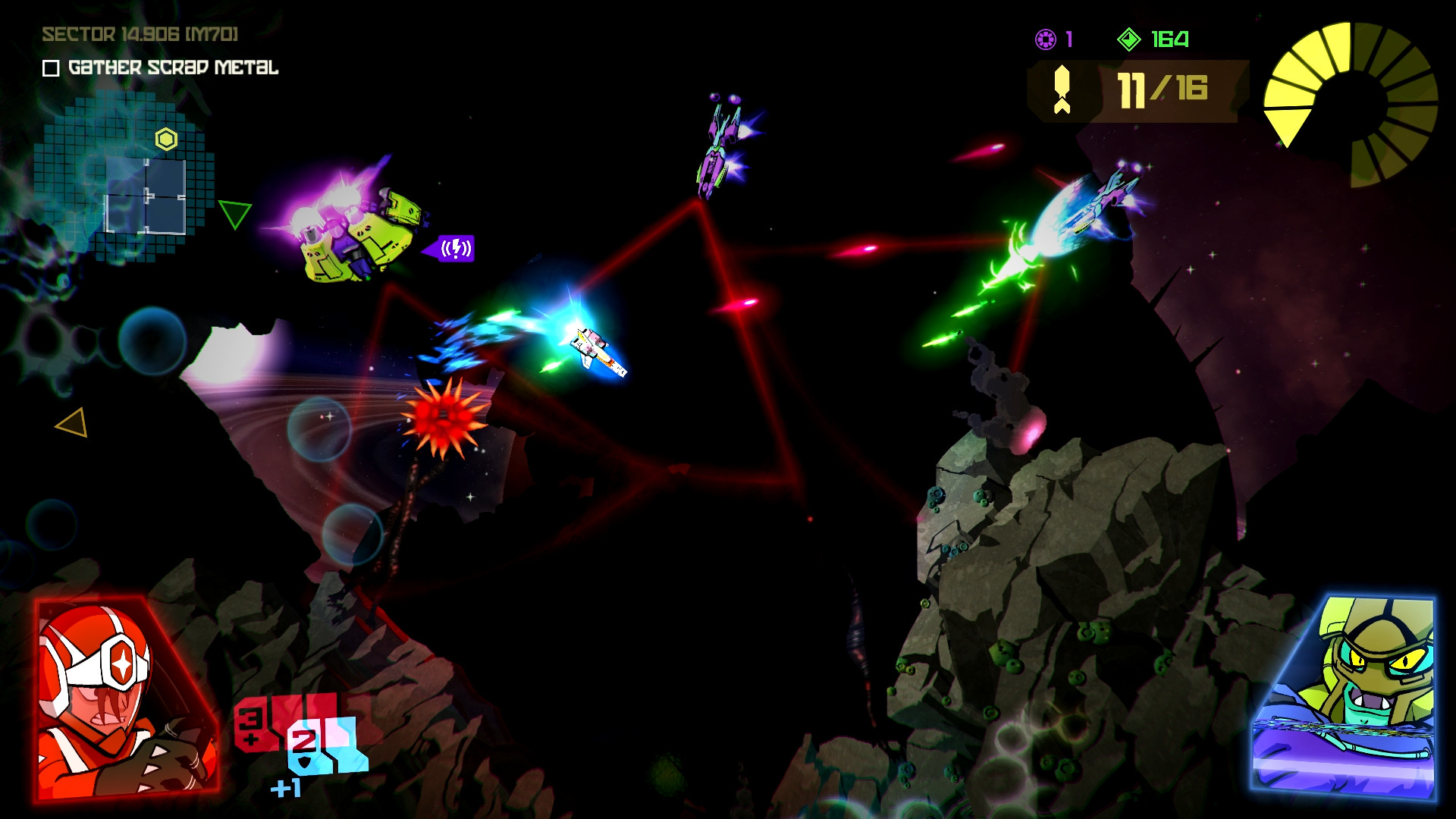

Galak-Z

Space is horrifying. Not in a shambling ruins of rotten flesh kind of way, but precisely the opposite.

Because it looks so unthreatening. The empty void of the vacuum of space is beautiful to observe. The beautiful colors of the distant nebulas, the warming glow of the distant stars, and the graceful arcs of distant planets and asteroids are all as beautiful as lying in the grass on a summer’s evening, star-gazing. However, out in that vacuum, there is no breathable air, horrific amounts of radiation, and enough cold and pressure to snap freeze skin and collapse organs.

Galak-Z is a game that parallels the danger of space. It is a high-speed shooter where every derelict ship, every enemy skirmish, every bug-infested asteroid is terrifying. Death is everywhere, and any tiny mistake could spell the end for its protagonist.

Galak-Z, however, manages to mitigate that danger by being a profoundly energetic arcade shooter in a personable space. The voice work, visual style, and sheer energy in every session builds up the action to feel very much like the 80s and 90s space adventures it evokes. No matter the risks, it’s never afraid to be a little cheerful, playful, and full of banter. Above all, Galak-Z is fun, no matter how threatening it gets.

Space is horrifying, but it’s also wonderful.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer, editor, and Features Editor for Haywire. He’s a fan of the sound of language, the sounds of games, and the sound of deadlines looming nearby. He sometimes says things on Twitter and his website, and has a Patreon if that’s your thing.

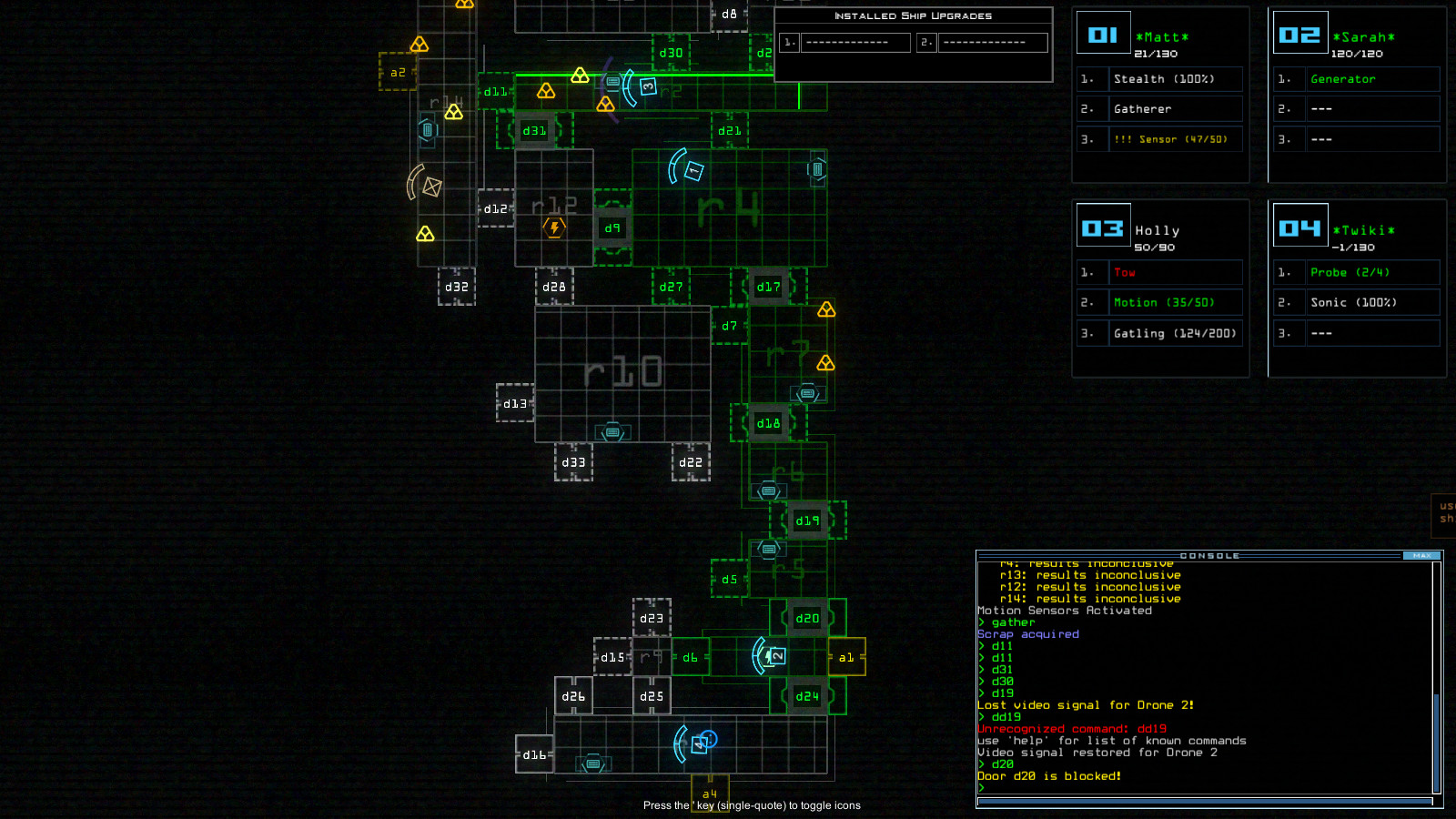

Deadnaut/Duskers

In a way, all games are merely interfaces, clever systems allowing us to interact with the world behind the screen. Yet some go a step further in acknowledging the importance of these interfaces and base their gameplay and even narrative around the very screens we stare at. One of the oldest of these games must be Hacker (1985), the grandfather of all later hacking epigones, which asked you to ropleplay as, essentially, yourself, sitting in front of your trusty computer. You’re an operator, and the game and its interface are your tools in manipulating a reality that exists behind the minimal abstractions offered on screen.

In Deadnaut and Dusker, this unseen reality is grim. Both take us to outer space, to a world filled with drifting, long-dead spaceships to board and salvage, in a clever mixture of themes appropriated from gaming classics like Space Hulk and Dead Space, but also Event Horizon and Aliens. In fact, Aliens serves as inspiration in more than theme: Expanding on Scott’s original motion-tracker scenes, Cameron introduced his viewers to an SF-version of military mission control, in which an operator directs and commands a squad of soldiers from afar. Squad members’ health and heart rate as well as video feeds, tactical maps and comms displays show a real-time, but abstract representation of the mission.

Both Deadnaut and Duskers take this idea of abstract, real-time, squad-based mission control and pit the player as the distant operator. Deadnaut’s protagonists are flawed and, more often than not, doomed human mercenaries with individual strengths, quirks and weaknesses, while Duskers offers a variety of upgradeable drones. Mechanically, both games are classic RTS stuff, combining strategical and tactical decisions and careful micromanagement with procedural universe and mission generation for endless replayability. But it’s the interface that takes center stage in both.

Deadnaut simulates a claustrophobic first-person view of our fully interactive operators console, complete with screens, rivets, scratches and gauges, while Duskers looks more like pure software, or like a cross between a futuristic ASCII roguelike and the aesthetic of technical or medical diagnostics. Where Deadnaut is haptic, concrete and, with its human cannonfodder protagonists, even personal, Duskers is abstract and, by even offering a command-line interface for faster drone management, technical. Sound, relayed back from the depths of the boarded ships, plays an important role in both.

These are games played by obscure remote control and visualized by abstract blips on mainly monochrome screens , but still – or rather because of this – both are nail-bitingly suspenseful affairs. They force us to imagine the reality behind the abstractions, by scattering their worlds with sinister narrative fragments and by punishing the careless player with swift, brutal demise. Deadnaut and Duskers offer some of the most atmospheric, but also frantic horror experiences of the past year.

Rainer Sigl is a carbon based lifeform mostly based in Vienna, Austria. He has been firing synapses to the tunes of videogames for a very long time.