2015: The Year of Gravity

What goes up must come down, like Flywrench, Kerbal Space Program, Gravity Ghost, Super Mario Maker, and CRAP! No One Loves Me.

Flywrench

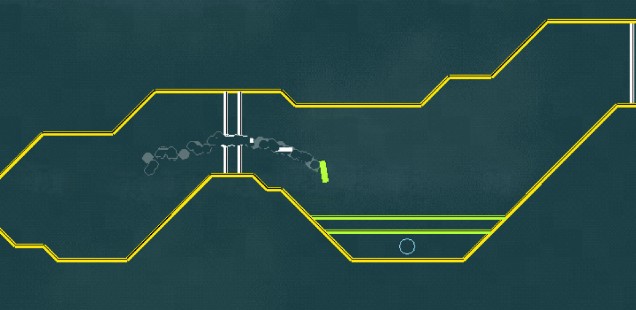

Messhof’s 2007 freeware classic Flywrench saw a welcome return in 2015. The basic mechanics of the game remain unchanged, but the campaign levels have been polished, a level editor and a soundtrack curated by Daedalus added. Flywrench‘s main mechanical hook is that your small spacecraft changes to one of three colors based on what it’s doing, and there are colored gates that you need to match in order to pass through them safely.

Its other mechanical hook is that it’s very difficult, with an instantaneous restart similar to Super Meat Boy. The result is an incredibly precise, incredibly compelling game that rarely feels frustrating, always challenging you to become more proficient with the mechanics. It does step over the line a little towards the end of the game, with several levels that require such speed and precision as to feel prescriptivist; only the perfect line through the level is sufficient for success, unlike earlier levels that allow you a bit more breathing space but always hint towards that perfect line. Still, this doesn’t mar what is otherwise an essential experience.

David Thatcher worked in the games industry as a QA technician for 10 years, and is now one half of the indie games studio TriCat Games, handling the majority of the art and audio tasks. His personal site is at giraffe.cat.

Kerbal Space Program

The world of videogames has developed something of a simulator problem over the past few years. What started innocently enough back in the ‘80s with Microsoft Flight Simulator has since spun out of control, now we’re simulating not just flying and city planning, but Euro trucking, football managing, and being a goat.

These simulators are great for sharing experiences with players who may otherwise never know what it’s like to fly a plane (or be a goat). But there’s a difference between being experiential and being instructive. Players of Flight Simulator may know what it feels like to fly a plane, and Roller Coaster Tycoons can relate to the stress of managing an amusement park, but players of neither game can in most cases come away from playing with an understanding of how these tasks actually work. Kerbal Space Program may not reach that goal, but it comes damn close.

We don’t like to think of our games as demanding things of us, and Kerbal does to be sure. The in-game tutorial reveals little more than how the controls work, but if you want to go to space, you need to understand real-world astronomical and engineering concepts. Kerbal Space Program is very much a wiki game, but the sheer joy and thrill of accomplishment when you finally touch down on a stellar body makes the high cost of entry more than worth it. As an added bonus, the game holds the rare distinction of being perfectly comfortable in a classroom or other strictly instructional setting. I can think of few games like it.

Patrick Lindsey is a game critic living in Boston. He co-wrote and co-edited SHOOTER, an ebook anthology of critical essays on shooting games. He also co-hosts Bullet Points, a podcast centering on critical discussion of shooters. He’s pretty sure he’s on an FBI watch list. Follow him on Twitter @HanFreakinSolo.

Gravity Ghost

I haven’t played many puzzle games with a story as touching as the one found in Gravity Ghost. The protagonist, Iona, has died and must act as a shepherd for animal spirits in purgatory. However, before her death, she believed her sister’s boyfriend Arthur was responsible for their parents dying at sea. Eventually, when she realizes her anger towards Arthur was misplaced, she helps her friends and family, who are suffering in the physical world from her past mistakes.

But the game has more to offer than a good story. The hand-drawn art style reminds me of a children’s book with vibrant neon colors that channel Dia de Los Muertos. It sounds good, too. My head was constantly bobbing to the beat of Ben Prunty’s tribal space tunes. Sometimes I would have Iona endlessly twirl so I could watch her hair move with the music instead of finishing a level.

Luckily, it’s an aesthetic that can be enjoyed by all. The puzzles have a gentle learning curve that isn’t too hard or repetitive. I never had to bang my head against a wall like in Fez or Braid; I just let gravity do the work for me and enjoy the ride.

It’s a wonderful tale about coping with loss. I wish the first time I played this was during that horrible week in January when one of my grandfathers, along with David Bowie and Alan Rickman, passed away.

Jefferson Geiger is a journalist and crtic from Colorado. His work can be found at GameSpot and Memory Insufficient. You can follow him on Twitter or at his website.

Super Mario Maker

Super Mario Maker is the kind of game we’ve all dreamed about, but never thought would actually get made. Plenty of games come out with robust creation tools and sharing options, but none of them have the weight of Mario behind them. Nintendo has handed over the keys to the Mushroom Kingdom, and the result is a beautiful mess of absurd and wonderful levels.

The level creation tools in Super Mario Maker are dead simple, and that’s great. Keeping it simple means that you can hand the gamepad over to just about anyone, and they will be able to put together their own level. It’s all intuitive. Shaking items changes them into their alternate version and feeding items mushrooms makes them bigger. Creating is simple and easy, but that doesn’t mean that you will be limited to simple creations.

Level creation is fun, but the ability to play others’ creations is what keeps bringing me back. I never knew that Mario levels could be so infuriating, confusing, or satisfying. I have learned just how far the limits are in Mario games. I have seen explorative, automatic, puzzle, musical, and downright mean levels. It’s so cool to check in and see a new trick or idea that someone’s incorporated into a level, pushing the limits a little further.

Super Mario Maker may not be the best game ever made, but it’s the game I find myself playing the most lately. There’s just nothing like winding down with randomly created Mario levels at the end of the day. It’s essentially infinite Mario, and that is just great with me.

Jake Crump is a writer based in Louisiana, where he lives with his wife and three rescue dogs: Eliza Doolittle, Captain von Trapp, and Dorothy Gale. You can find more of his work on his blog, TheDweebJar, and follow him on Twitter.

CRAP! No One Loves Me

CRAP! No One Loves Me was a stealthy release from the videogame development collective Arcane Kids. The Arcane Kids are primarily notorious for their bastardizations of 90s game mascots, represented by the games Bubsy 3d: Bubsy Visits the James Turrell Retrospective and Sonic Dreams Collection. The aforementioned games work by pairing nostalgia and irony to create unsettling weirdness in reference to the works they ape. While it employs similar techniques, CRAP! No One Loves Me rather reads as a genuine love letter to late 90s games and their primitive 3d graphics.

CRAP! No One Loves Me’s first impression is ironic and weird. You select a character via a Tinder-esque interface. The camera pulls out to show your chosen character in a vape shop. The game only begins after you defenestrate your character and navigate them into a dumpster. Revealed next, the core mechanic involves driving a coffin down a twisted and broken bobsled track. You use jumps and boosts to navigate the track’s holes and curves, eventually launching the coffin into an iPhone screen to complete the level. As it progresses, the game ramps its difficulty up steeply, almost to aggressively mean degrees. The levels are decorated by pyramids, giant black figures, and other strange constructs, all rendered in hot and cold gradients reminiscent of a childhood notebook cover.

The combination of these transcends simple weirdness and becomes a charming, nostalgic experience, reminiscent of going to Blockbuster and renting a game based on box art. Its VCR scanlines, low-poly models, and scattershot aesthetics inspire the same feelings of wonder and possibility that made my formative game experiences feel important. The hours I spent exploiting engine glitches in Counter Strike Source to master user made surf levels are sublimely distilled in the game’s bobsledding coffin mechanics. CRAP! No One Loves Me might read as a collection of “Only 90’s kids will get this” references, ranging from PS1 aesthetics to a modern millennial irony, but to me, it was the perfectly tailored selection of references, making it my gaming experience of 2015.

Spencer Winson is a game developer, making mobile games professionally, and working on his personal projects on the side. His projects can be found at his website.