Opened World: Nowhere Fast

Miguel Penabella obeys the speed limit.

In the 2015 game Three Fourths Home, protagonist Kelly travels across Nebraska longing for some sense of salvation and direction. Created by [bracket]games—comprised of writer and developer Zach Sanford and composer Neutrino Effect—Three Fourths Home resembles a visual novel that presents a drama of familial breakdown over the course of a single telephone call. Kelly drives home in her car, and during the telephone conversation, years of emotional baggage from her and her family members are steadily brought to bear. While this weepy tale of crushing personal failures is frequently overwrought, the game does inventively convey such themes with its uncluttered visual design. If Three Fourths Home is a game about a young woman journeying home, then its imagery shrewdly undercuts her ability of movement, suggesting an ever-tightening chokehold on her freedom.

Three Fourths Home centers on two fundamental actions, accelerating the car and choosing Kelly’s responses during her phone call, that inform the themes and narrative of the game. The act of driving is mostly perfunctory because the road is unendingly straight, allowing the player to focus on soaking in the details of the conversation. The phone call begins confrontationally as Kelly fields a string of questions from her worried mother Norah, but then it gradually eases to a sadder, more digressive exchange about familial sorrow. Much like in Kentucky Route Zero, the dialogue choices factor not as a means to steer the outcome of a narrative towards numerous possible end states, but as a way to inflect Kelly’s tone towards her family and to teach players about the situation. Plenty has been written about the domestic troubles that come out over the course of the phone call, like the thorough exploration of rural poverty and oppressive power structures by Melody for her blog, so that kind of analysis isn’t the point of this piece. Rather, it’s worth noting how Three Fourths Home’s classical melodrama is visually framed and thematized.

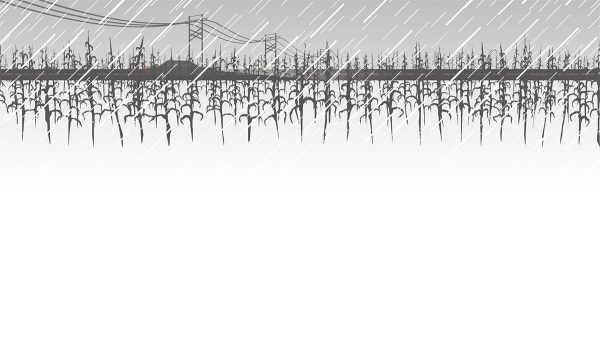

The central theme of Three Fourths Home is the frustration of movement and independence when grander problems like work-related accidents or financial shortcomings circumscribe individuals within strict boundaries, and these ideas are replicated visually. The top half of the screen depicts Kelly’s car on the road, cruising by cornfield after cornfield in a worsening thunderstorm and occasionally passing sights like lonely H-frame transmission lines or faraway wind turbines. The bottom half displays the text of the phone conversation like a Twine game, bouncing from a family member’s words to Kelly’s potential responses. What’s noteworthy is how the car remains fixed on the top-left side of the screen as you accelerate. For the entirety of the game, this car will remain rooted to this spot, seemingly immobile if not for the passing fields and rainfall that animate it with an illusory sense of movement. Like a trick of vintage Hollywood special effects where an actor walks on a treadmill as a scrolling backdrop moves behind them, the world moves around the subject who is actually just stuck in one place. In Three Fourths Home, Kelly remains motionless even if she thinks she’s moving; the world marches on indifferently.

This visual dichotomy of mobility and stasis ties into her mother’s fears of Kelly’s future in Nebraska. She worries that Kelly is falling into a familiar pattern of behavior that mirrors her own, in that she returns to her childhood town only to find a dead end job and will not be able to escape from Nebraska to pursue her own dreams. Over the course of the game, Norah reveals that she never graduated college, reflecting Kelly’s role as a recent college dropout. Likewise, Kelly returns to Nebraska to secure her father David’s blue-collar job that Norah knows she will grow to detest. In the crucial additional sequence added to the extended edition of Three Fourths Home, Norah’s voice identifies Kelly’s suppressed fears of worthlessness, and that she will not be able to follow through with her professional aspirations because of this. Norah’s words crash with sobering force, asserting, “This is what you’re really thinking. Deep down, buried beneath all of the other garbage you’re holding on to.” By dropping out of college and having to be dependent on her parents again, Kelly is consequently stuck in place and unable to move forward and outward from her failures.

Kelly’s defiant act in the beginning of the game to drive out to her grandparents’ old farmhouse for solitary contemplation actually just ignores the inevitability of addressing the problems back home and time’s incessant march forward. Like Campo Santo’s game Firewatch released this year, characters escape unsavory household troubles by disappearing into nature and connecting with an unseen, sympathetic contact either by phone or by walkie-talkie. Just as how Firewatch’s central forest fire serves as an allegory for a nagging sense of guilt and how suppressed anxieties are always imminent, Three Fourths Home’s tornado suggests Kelly’s restless guilt and dread over avoiding her familial problems. As the thunderstorm intensifies, these problems are foregrounded: David’s phantom pain after having lost his leg in an accident and subsequent alcoholism to numb the pain, Norah’s marital regrets for having settled down in a town she feels she’s rotting in, and Kelly’s brother Ben’s move to a new therapist too far away for him to regularly see. These numerous difficulties threaten to permanently fracture her family’s well-being, and the impending tornado suggests a divine manifestation of total ruination.

The Midwestern landscape also exacerbates Kelly’s anguish and constriction, neatly subverting ideas of pastoral bliss. The flat, panoramic expanses of Nebraska would seem to represent openness and boundless freedom, but for Kelly, that world is a place of regression and personal oppression. That she’s confined to the cramped space of her car for the entire duration of her trip further aggravates that feeling. When Kelly drives deeper into the storm, the car is totally swallowed up in inky blackness, and the only glimpse of the world outside comes from a single shaft of narrow light pouring out of her car’s headlights. For a place that promises freedom, it ultimately proves airless and compressed. The intimate space inside the car shelters Kelly from the hazardous weather outside in a space of solitude and safety, but it also disconnects her, leaving her completely alone.

One can’t help but think of the 2013 Alexander Payne film Nebraska, a similarly black-and-white road trip movie about characters escaping obvious domestic pitfalls by trekking into the landscape while a protagonist reconnects with a parent. Furthermore, the 2013 Steven Knight movie Locke warrants comparison to Three Fourths Home as a drama set entirely in the space of a car as its protagonist juggles a familial breakdown over a series of telephone conversations during a single night. Three Fourths Home recalls these narrative precedents, settling into familiar themes of interpersonal disconnect and spatial confinement within the boundaries of an automobile. Where the game breaks free of its prosaic tragedies comes late in the extended edition of the game in its flashback epilogue in Minnesota before the events of the main storyline. Here, Three Fourths Home displays nuanced insight towards Kelly’s woes and actively unpacks her complicity in the family’s gradual breakdown.

During the flashback sequence when Kelly studied in Minnesota, she no longer drives in a car but is instead waiting at a bus stop while conversing with her mother on the blunt hardships of the family back home. If the main game in Nebraska represents the surface of her familial burdens, then this epilogue is the subconscious where unspoken thoughts and insecurities bubble up in a dreamlike haze. This sequence appears as though Kelly is remembering her time in Minnesota through the lens of the events that transpired in the main game. In addition to choosing the standard responses during the phone call, Kelly now has the option to choose dialogue in brackets. These choices alter the landscape surrounding Kelly, as trees fall away and are replaced with new ones and the ominous silhouette of the farmhouse reappears and vanishes on the horizon. The bracketed dialogue choices lead to ugly exchanges that seem more like unconscious thoughts like insecurities that can’t be shaken loose rather than an actual conversation that transpires. It’s as though Kelly needs to hear the sting in her mother’s words to lift her out from her stasis, putting the ruined farmhouse back into perspective as it looms over like a storm cloud.

The crucial difference with the epilogue is that Kelly can actually move within the frame, but Three Fourths Home still manages to arrest her movement in a surreal way. The feeling of being stuck in one place carries over because although Kelly can now walk from the left to the right side of the frame, she can never move past the same recurring surroundings. Moreover, if she stops walking, then the bus stop reappears as though Kelly hasn’t actually been walking away from her initial spot and is really rooted in one place. Three Fourths Home does offer a glimmer of relief and an answer to how Kelly can ultimately break free of her despair. When the bus finally arrives and Kelly boards it, she’s granted an action that has been denied to her for so long: leaving the frame.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.