Opened World: Framing Violence

Miguel Penabella knows his shapes.

Dispensing with elaborate gameplay mechanics and narrative context, Pippin Barr and Rilla Khaled’s 2015 game A Series of Gunshots (playable in your browser here*) relies on simple, effective imagery instead. Barr and Khaled, both lecturers at Concordia University and the former the author of the book How to Play a Video Game, think about games academically and critically. Comprised of a series of five colorless, static outdoor scenes, the world of A Series of Gunshots is minimalist and funereal. Of particular interest is the shape of the videogame: its square 1:1 aspect ratio frames the gun violence within a claustrophobic box, conveying airless urban entrapment. I’m reminded of the 2014 Xavier Dolan film Mommy, whose similar 1:1 aspect ratio was extensively discussed and praised for its evocation of album covers and Instagram photography, as well as for its emotional directness. Why then don’t we talk about the relationship between aspect ratios and visual framing in videogames as often? Moreover, what does it mean that a game chooses to depict violence in such a specific visual frame?

Many players criticized the widescreen presentation of The Evil Within (2.35:1) and The Order: 1886 (2.40:1) as annoying hindrances to gameplay without first examining how these aspect ratios are meaningfully used. Rather than entertain the possibility that the widescreen aspect ratios in those games underline a sense of constricting oppression or reflect their characters’ limited worldviews, many called for the removal of the black bars to expand the image. Carefully considering the ways videogames are framed is a valid aesthetic inquiry; the question of how images are framed carries with it aesthetic, political, and ideological gestures atop its formal properties.

A frame is not only the structural support around an image, but can also refer to the system that underlies forms of discourse and meaning, like how there are “frames of interpretation” of any given theory or discipline, or how political ideologies can be “re-framed” in news media. The commonality between the two definitions is a sense of enclosure—how images and meanings fall within distinct borders. A Series of Gunshots is about both the literal frames within the image—windows, doors, garages, decorative panels—and also the discursive frame of gun violence and its representation in videogames. With A Series of Gunshots, they deconstruct and defamiliarize the act of shooting and return to questions of visual entrapment and concealment.

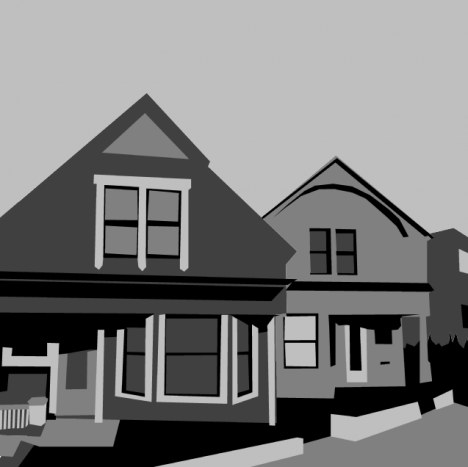

A Series of Gunshots lasts about ninety seconds total, revolving around five discreet scenes lacking in gameplay instructions or context. No characters are seen, no music or dialogue is heard, and no discernible storyline can be immediately gleaned from the provided images of urban still life. Upon hitting a key, the sound of a firearm rings out and a small flash of white light appears in a darkened window, intimating an act of unseen violence that has just occurred. Anywhere from one to three gunshots can be elicited in a scene before the game fades out and a new one takes its place, totaling five separate locations. These scenes are randomly chosen and players can replay the game to visit different areas. Such locales include windows overlooking a quotidian shop, an unremarkable apartment block, a pair of suburban homes, and a parked truck half-swallowed in the shadows of a building’s loading dock. Rows of blackened windows recur in each scene, framing the gun violence enacted with simple keystrokes and hiding any necessary details that could provide context.

The fades between scenes carry over from Barr and Khaled’s previous game What We Did, also a boxed-in 1:1 game concerned with largely unseen characters finding themselves unable to escape the consequences of some past wrongdoing or the chokehold of a monochrome urban landscape. What We Did’s final chapter “We Give Up” anticipates the lonely, voyeuristic violence of A Series of Gunshots, and its static scene of a moonlit construction site housing the sight of two gunshots could very well be transplanted onto the latter game. Both games are structured around absence and elisions because the violent act is unseen and out of frame. The black screens that separate one scene from another in both What We Did and especially A Series of Gunshots suggest things left unsaid, and narrative and visual fissures where some ugly reality is invoked from the void.

Moreover, the game’s cold, precise framing of building exteriors in a square frame recalls autopsy photos like a noirish crime scene investigation. Scenes feel stuffy and constricted, trapped within the tight letterboxing of the square aspect ratio. The aforementioned film Mommy depicts characters—particularly its self-destructing teenage protagonist—that are confined by socioeconomic and personal hindrances, and the 1:1 aspect ratio allegorically works to further shrink their prospects within such a tight space. When the screen enlarges to a widescreen presentation roughly midway through a particularly joyous scene, the claustrophobic frame pulls apart and we feel as though characters are suddenly liberated from their anxieties and problems if only for a moment. The film allows audiences to share in this catharsis by letting the space breathe. When the frame reverts back to a tight square, we’re reminded of the difficulty in escaping the personal entrapment that these characters struggle with throughout the movie.

A Series of Gunshots denies the player any such breathing room, instead multiplying its oppressive visual frames and reducing any opportunity for escape. The experience recalls an ever-shrinking series of entrapments like a Matryoshka doll: the frame of the computer screen contains the window of the internet browser which contains the square frame of A Series of Gunshots which contains the many windows and doorways that contain the unseen characters. The game is comprised of frames within frames, conveying inescapable constriction in a world that’s bleak, lifeless, and unresponsive.

In thinking about framing, what remains unseen is just as important as what’s visible in the frame. Things invoked out of frame are loaded with meaning and carefully considered, and the enacted violence in A Series of Gunshots is concealed and left for us to ponder. The lack of narrative context means that entire lives are hidden from view, and the gunshots could refer to homicide, self-defense, self-inflicted violence, or even an accident. In a statement written by Pippin Barr himself, he notes the game’s project in “abstracting the idea of ‘who’ and ‘why,’” and players are consequently left to fill in the blanks. That there are more than five randomly selected scenes available suggests the widespread nature of gun violence and how much goes unnoticed beyond just one playthrough. Like the gunshots of the game itself, many other scenes are hidden from us, and this kind of violence is repetitious and common in any given milieu.

The frames within frames of A Series of Gunshots also gesture at metafictional possibilities, particularly the notion that windows resemble televisual screens that allow us to voyeuristically take pleasure in violence. We play the game when we press the keyboard, but we’re also spectators. Windows screen violence, much like the television sets and computer monitors on which videogames are played. Writing for Offworld, Leigh Alexander also identifies the game as partly about the act of spectatorship: “all you can do is press a key and see.” Like the protagonist of Alfred Hitchcock’s film Rear Window—confined to his apartment and helplessly looking out across a courtyard to violence being carried out through uncurtained windows like he’s watching a movie—we as players are helpless spectators trying to make sense of inevitable violence.

A Series of Gunshots pushes back against the ideological and formal structures of gun violence in videogames by acknowledging our complicity in witnessing and prompting it. Guns may not be visible in the game, but their presence is implied by sound and by a play of light and darkness which serve as signifiers of action. Thus, gun violence is stripped of significance; these acts are random and devoid of pleasure or rewards like a typical shooter game. Gun violence isn’t stylized for entertainment purposes, but is instead given a minimalist style for the purpose of robbing it of substance. What matters is the haunting, lingering aftermath when human figures are removed. Writing for Kill Screen, David Rudin notes how “all agency still belongs to the shooter. He or she may feel guilt, but those who are shot remain invisible.” The game works as a meditation on violence, though we must work to come up with a corrective that counters thoughtlessly problematic images in games. We participate in acts of violence but often lack critical mindsets to question such imagery. A Series of Gunshots nakedly depicts violence, urging us to also consider all the things left unseen.

The first step is rethinking how violence is represented in such media. I can’t think of many games that depict its heavy impact and its seriousness for a medium that praises itself on M-rated violence and shooting. A Series of Gunshots plainly frames gun violence, stripping away the shooter genre to its essence: press a button to shoot a gun. The questions that arise afterward—Who shot the gun? Why was the gun fired? What are the consequences of this violence?—serve as templates for shaping meaningful contexts in a videogame. Guns don’t necessarily need to be centered or even visible in the frame for its impact to be felt. In framing violence this way, Pippin Barr and Rilla Khaled gesture at the unspoken and unseen subtexts that may not be easily discernible but nonetheless remain present in any videogame.

*There may be trouble playing this game on Google Chrome, so try a different browser if problems arise.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.