Opened World: Dancing On My Own

Miguel Penabella jams to Sayonara Wild Hearts.

Tune into Top 40 radio, shuffle a Spotify playlist, or play any TikTok video, and you’re bound to hear teenage popstar Olivia Rodrigo belt out the irresistible bridge of her breakout hit “drivers license.” Over anthemic production, she croons, “Can’t drive past the places we used to go to,” enunciating each word with anguished importance before a cleansing confession: “Cause I still fuckin’ looove you, babe…” It’s the undeniable hurt of young love in all its melodrama. These kinds of songs are companions. Sometimes you may find yourself alone on a bus at night, but when you pop in a pair of earbuds, your favorite song offers a warm embrace with a chorus incapable of leaving your head. Pop music offers a chance to heighten such mundane moments of everyday life. It soundtracks heartache with bubblegum synths and thunderous hooks, inspiring concertgoers, karaoke songsters, and drivers stuck in traffic to gleefully belt out sad lyrics without even realizing just how sad those songs really are.

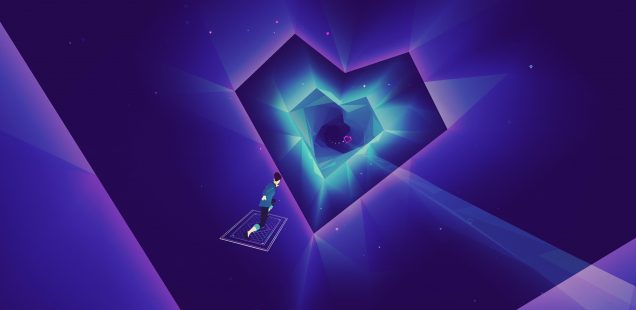

For many of us, music serves as the ultimate salve for sadness. Songs about heartbreak, like Robyn’s “Missing U” or Lorde’s “Liability,” are deeply sad songs mired by hurt, but motivated by the belief that things will ultimately be okay in time. This is the emotional register of Sayonara Wild Hearts, Simogo’s rhythm game homage to the transcendental power of pop. The game is framed in terms of isolation and love lost, opening with the protagonist in her room, curled up alone in bed. A celestial narrator voiced by Queen Latifah introduces the protagonist as a “heroine from the shards of a broken heart,” and that “her heart broke so violently that her sorrow echoed through space and time.” Like the best of pop music, Sayonara Wild Hearts takes this sorrow and surrounds it with movement, transporting the protagonist out of her bedroom and headspace, propelling her towards radical moments of beauty, and engaging the senses with a genuine sense of visual and sonic wonder. Pop songs composed by artists Daniel Olsén and Jonathan Eng and occasionally animated by the ethereal vocals of Linnea Olsson serenade our journey through astral highways resembling Rainbow Road in neon or an interdimensional Out Run. Players guide the masked protagonist as she avoids obstacles, collects hearts, and fends off enemies, all in sync with the music. At its core, Sayonara Wild Hearts celebrates the art of pop music, structuring its levels around its mesmeric beats and hooks. It understands pop music’s vitality; over the course of twenty-three levels, the game presents pop as liberating and life affirming.

The sensation of heartbreak is akin to falling out of rhythm. Mired in the depths of depression or personal aimlessness, returning to the groove of routine can feel impossible. Sayonara Wild Hearts is about rediscovering that beat and stepping back in tune. Alone in her apartment, the protagonist radiates a sense of restlessness, visualized in the game’s constant flow of movement and velocity that finds her accelerating, tumbling, and freefalling through a dreamlike prism of her inner life. The game transports players through settings ostensibly filtered through her negativity, with locales dubbed Lovedead City or multiple levels titled “Heartbreak,” illuminated in pulsating neon lights of glowing purples and pinks. The remedy for this melancholia, the game seems to suggest, comes from the escapist rush of music and movement. With its nightclub aesthetic, Sayonara Wild Hearts channels that sense of collective movement with others in loud places, as though the whole world were moving as one, lockstep in deliriously satisfying rhythm.

The opening level, set to a remixed “Clair de Lune,” begins slowly as the protagonist takes her first strides towards synchronicity again. We share in her journey of rediscovery, sliding left or right in a leisurely pace to collect lost hearts and familiarizing ourselves with the game’s sense of forward motion. Soon though, the game quickens and we must surrender to what feels right, as the music crescendos while the track dips and ascends like rolling hills. Another early level, “Doki Doki Rush,” finds the protagonist propelling her motorbike through the city streets of Hatehell Valley, weaving in and out of traffic, rocketing through passageways, and springing into the air. In moments of sadness, simply leaving home and changing the scenery by taking a stroll around the neighborhood or driving somewhere with the windows down can drastically alter one’s mood for the better. Sayonara Wild Hearts takes this premise by flinging its protagonist through space and time with levels that corkscrew down tunnels of light, inverting the player-character, and enveloping us in a breathtaking spectacle of movement and sound. We listen to pop music because its upbeat tempo and soaring production is often restorative, cathartic, euphoric. Sayonara Wild Hearts channels these feelings through carefully choreographed camera movements in sync with music and gameplay. Cinematic camera flourishes maintain a sense of momentum, like when the camera pushes outward into a wide-angle shot as the track circles in on itself and spirals upwards like a staircase to the heavens and the soundtrack swells accordingly. Elsewhere, the protagonist hurdles through the air as the camera rotates around her, emphasizing the rush of temporary flight and weightlessness. Through these choreographed maneuvers, we’re allowed to feel ourselves as a part of a propulsive music video without having to worry about controlling anything more complicated than lane-changing.

As the game rapidly accelerates, much of Sayonara Wild Hearts may feel overwhelming or that things threaten to spin out of control because so much sensory spectacle barrages the mind at once. And yet, this game isn’t particularly taxing to play; a sense of control always persists, even as the screen cascades with oversaturated, dizzying visual splendor. Failing to thread through a tight tunnel or dodge an enemy attack at the right time results in a quick, forgiving reset, with neither points lost nor much time wasted. Even the music neatly rewinds so that the track feels continuous, like a small remixed moment by a cosmic DJ returning us to the beat. As a result, players will likely never feel bogged down in one challenging area—repeating the same problem over and over again—which would squander the harmony and forward momentum that are so essential in maintaining the game’s sensory immersion, as calling attention to the artifice and mechanics of gameplay—game overs, resets, point systems—would sabotage the game’s musical flow.

In these ways, Sayonara Wild Hearts feels less like a traditional game than a visual album, seeking to immerse listeners in richly curated worlds, akin to the lush diasporic tableaux of Beyoncé’s Black Is King to the dystopic fever dream of Sturgill Simpson’s Sound and Fury. Perhaps the closest forebearer is Daft Punk’s Interstella 5555, a cosmic voyage of dance jams that blast the senses. That the game is structured around twenty-three individual tracks, like a deluxe edition LP, adds to this impression. There are moments in Sayonara Wild Hearts where gameplay and music complement each other the way visual albums wed cinematography and sound. The kaleidoscopic “Forest Dub” level, for instance, filters its woodland surroundings as if through the intoxicated lens of hallucinogenic drugs, resulting in a choppy sense of forward movement as though stop-starting to the beat of the song. Rather than race forward seamlessly, the motorbiked protagonist seems to pulsate in sync with the music, and the world itself appears to inhale and exhale with each beat. When the trail falls away, the protagonist then bounces atop magic toadstools and later collects a series of mushrooms that comically balloons the character in size, adding to this psychedelic aesthetic like a drugged-out party in the forest. In “Parallel Universes,” twin antagonists snap their fingers to the beat of the song, with each snap swapping the layout of the track. One road may be open and full of collectable hearts before the game snaps to another reality with obstacles in the way before snapping back to that first layout. You’re listening as much as playing; here, careful attention to the tempo of the music facilitates your ability to navigate between realities to the beat.

When we think about pop music, we often frame the genre in terms of escapism, partying, and corporate spectacle but that doesn’t mean that it’s devoid of genuine emotion. For the protagonist of Sayonara Wild Hearts, pop music serves as a means of self-discovery through a celebration of the feminine and emotionally resonant. Occasionally, the protagonist will face off against enemy characters (presenting both male and female!) who flirtatiously beckon, and fight scenes choreographed to the music resemble dances instead of duels. In the game’s joyous final sequence, the protagonist removes her mask and returns to segments of each past level, combatting enemies with kisses rather than knockouts. She sheds the mask that serves as an emotional barrier, taking strides towards self-acceptance in a finale that’s goofy, playful, and fun. The game draws from pop music anthems that celebrate queerness and self-love, like the work of Lady Gaga, Janelle Monáe, or Carly Rae Jepsen that translate difficult feelings into words. I’m reminded of Nicole Clark’s thoughtful observation that the character’s narrative arc isn’t about becoming an impervious hero, but “an informed return to your initial state.” If the game is all about finding one’s rhythm after being mired in a depressive rut of negativity, it’s fitting then that Sayonara Wild Hearts ends with the closing image of the protagonist back at her apartment but inspired to take out her guitar and play. It marks a moment of genuine expression, and it’s the first time we hear her voice. Her longer hair suggests the passage of time, as though she has grown through her heartbreak after many months. As artists like Romy sing, we go to loud places to find people to be quiet with; pop music restores the soul and allows us to connect with ourselves and others. By outwardly expressing feelings wholeheartedly, it cues listeners to focus inward on those emotions, so that we may find our groove again.

Miguel Penabella is a PhD student investigating slow media and game spaces. He is an editor and columnist for Haywire Magazine. His writing has been featured in Kill Screen, Playboy, Waypoint, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.