Live Your Own Way: What Running a Hostess Club in Yakuza 0 Can Teach Us About Life Under Capitalism

Harry Mackin goes a little crazy in the process.

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.” – Ursula Le Guin

There’s a kind of second puberty that happens to all the sorry saps of capitalism. It happens when you realize that all the parts of you that you hold dearest—the things you believe and the reasons you believe them, the person you want to be, the ideas you were supposed to love and the people you were supposed to hate—were all imposed upon you, and for nothing more or less than the purposes of profit.

They shaped you to be the way you are because it made you an asset: consumer and product both, simultaneously. They taught you to conflate buying what they’re selling with loving the world, loving your loved ones, loving yourself. Everything you do that makes you feel like yourself, that makes you feel like a good person, is actually about making them money.

It’ll change the way you see everything, slowly but surely. Do you really like this? Do you really want this? And, always, cui bono?

It only slows down when you finally spend so much time introspecting and rationalizing and compromising and self-loathing that you’ll think you’ve scraped together some version of yourself that you can live with, carefully. Then it will happen again.

As you’ve no doubt surmised, this is an article about the adorable dress-up game in Yakuza 0.

Yakuza 0 is a prequel to the original Yakuza series. It takes place in December 1988, at the fevered climax of an era known as Japan’s “bubble economy,” a time of world-historic economic overexpansion and real estate and stock market price inflation. Predatory speculators took advantage of government policies designed to promote the marketability of assets and ease access to capital, creating a period from 1985 to 1991 when investors could borrow vast sums easily and use it to make ludicrous amounts of money overnight by rapidly buying and then re-selling stocks and real estate. This created an economic climate where asset prices soared, low interest and discount rates made overambitious investments possible, and a culture of aggressive speculation ran rampant.

As the game characterizes it, it was a time of wild excess. Salarymen waved down cabs with stacks of hundreds of thousands of yen. Real estate fortunes were made and lost overnight. All the old rules were thrown out and anything was possible. Meanwhile, in the shadows, the same predators that manipulated the public into feeling this newfound sense of control and possibility ensured the old rules didn’t change a bit.

Yakuza 0 takes place in these shadows. It features the youngest versions of the franchise’s heroes we’ve seen at this point as they’re just getting started in the Yakuza underworld. The tattoo on protagonist Kiryu’s back is still unfinished; he’s still figuring out who he’s going to be and why. But the biggest surprise of the game of all is the ability to play as secondary protagonist Goro Majima for the first time. This version of Goro Majima is starkly different from the man series fans know.

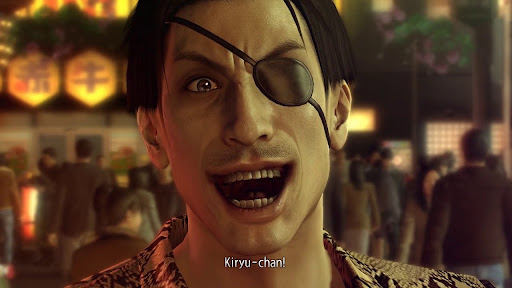

From the first Yakuza on, Goro Majima is a seemingly psychotic, amoral gangster who lives to hound series protagonist Kiryu Kazuma, alternatively helping and hindering his would-be rival in his own baffling, obsessive ways. If Kiryu is Yakuza‘s Batman, then Majima could be considered something like an antiheroic Joker (Mark Hamill even played the character in the English dub of the original PlayStation 2 game).

Yakuza 0 reveals the whole persona to be an act. And it reveals that farce by showing us who Majima was, before he better understood the world of which he played a part.

When Yakuza 0 opens, Majima is Sotenbori’s legendary “Lord of the Night.” He runs the red light district’s most popular cabaret, navigating the complex politics of Osaka’s nightlife with seemingly effortless grace and style. As soon as he slips backstage, however, we see that this, too, is an act.

Off hours, it’s revealed that Majima is a prisoner. He works at the Grand Cabaret to pay his debt to the Yakuza family that expelled him. Majima takes all the shit the Yakuza underworld can throw at him lying down, one yen at a time, until he can pay his way back in on their terms.

The problem is, those terms keep changing. He can’t or won’t see it, but we can all too clearly: Majima’s the perfect profit source for his captors. His virtues—his need to make things right with his debtors—are the only thing he has left to recognize himself with. They’re also what ensures he’ll never get out.

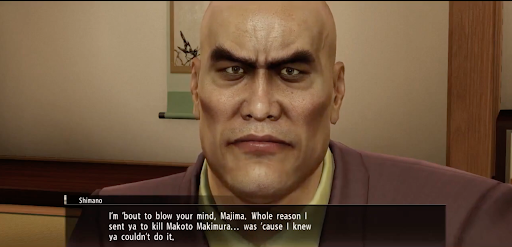

They keep moving the goalposts: the very first time we see Majima interact with the Yakuza, they raise how much he owes… again. Hell, eventually it’s even revealed they set him up to fail, just so they could use him.

At every twist and turn of the plot, Majima’s abusers in the Yakuza manipulate the best parts of him for their own profit. He is a known commodity to them precisely because he possesses the morality they can manipulate. Just like the rest of their victims, they dangle something he wants in front of him and reap the profits.

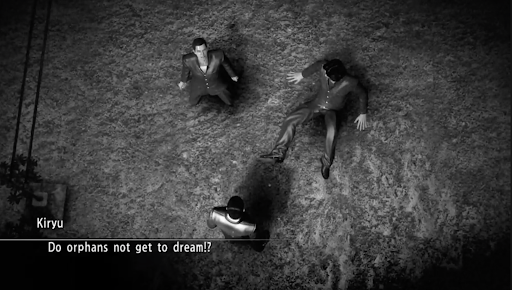

And the most bitter irony of all is that Majima (and Kiryu’s) manipulators gave him those morals in the first place. Both Majima and Kiryu joined the Yakuza for apparently altruistic reasons – to stand for something. Some lost ideal of the noble Yakuza—defenders of the downtrodden, masters of their own destinies—was all either of the lost boys had to hold onto growing up. And it was all a lie fed to starry-eyed young men so the people who never really believed in any of it could profit off of their futile striving. Sound familiar?

As Yakuza 0 reveals, Kiryu and Majima become who they are because they refuse to give up this altruism. But, as Yakuza 0 also threatens, this same heroism may make it possible for their manipulators to exploit them forever.

Is there any way out? The obvious solution is the answer Majima’s abusers themselves presumably arrived at: nothing is true. Morality, virtue, and all that jazz are for suckers. To be anything but a sucker in a world like this means to give up on all of that and pursue one thing: profit. Beliefs are just tools you can use against the people who hold them.

Based on who he seems to be in the other games, it might seem as though Majima comes to this conclusion by the end of Yakuza 0 himself. In the game’s greatest twist of all, however, it reveals that Majima’s act actually serves a very different purpose. And it reveals this, at least in part, through its adorable little dress up game.

Early in Majima’s story, while running errands for the Grand Cabaret, Majima stumbles across a smaller cabaret club in the district called Club Sunshine. Club Sunshine is, frankly, the laughing stock of the night world. They’re hopelessly naive and out of their depth. Their building is shabby, outdated, and in a grim part of town. Their “number one girl” is so shy around men she can barely make herself speak. Their owner is a rookie who doesn’t know the first thing about running any business, let alone a hostess club. Worst of all, they have some seriously naive notions about what being a hostess club in a nightlife district actually entails. These quirks make their operation more than a little ridiculous… not unlike a man who joins organized crime because it sounded heroic.

Majima, patron saint of lost causes that he is, decides to take Club Sunshine under his wing. In stark contrast to all expectations and in keeping with his ridiculously earnest personality, Majima doesn’t change what Club Sunshine is all about. Instead, he doubles down. Players must recruit girls from all across the nightlife district, each with their own skills, strengths, and weaknesses, and carefully develop these strengths and weaknesses via a leveling system. Girls gain experience from working; they perform better when you pair them with patrons who respond to their strengths and when you treat them well, making sure they don’t work too much and their customers don’t get handsy.

At the center of this minigame are the training sequences. Majima takes each platinum rank girl out for private lessons… which consist of completely straight, date-like conversations in which Majima gets to know each girl better.

Players get to know their personalities, their aspirations, thoughts, history, and secrets. You encourage them, help them with their personal and professional problems, and, most of all, provide a safe place where they can be themselves without the constant fear of manipulation they’ve grown all too accustomed to (again, sound familiar?).

Majima relates to these women as they tell story after story of disillusionment, of getting in over their head after just trying to do something good. All he does, all he can do, is comfort them, tell them they’re not alone, that they’re not “stupid” for wanting what they want or doing what they do, no matter what the world tells them. The women’s stats improve not as they get better at “playing the game” but as you encourage them to be more comfortable with who they are.

Against all odds, the ridiculous earnestness of Club Sunshine starts beating out the less scrupulous clubs in Sotenbori. As you “defeat” the other clubs, their girls join Club Sunshine… and undergo their own training with Majima. The Club gets bigger, more women join in, a family starts to grow… and before you know it, you’re the most successful club in the city.

Majima’s experience at Club Sunshine mirrors his and Kiryu’s arcs in the main narrative. Neither man gives up their absurd adherence to an ideal that never really was. Instead, the harder the world tries to divest them of their beliefs and punish them for sticking to them, the harder they hold on. And, crucially, the more they extend empathy outward to everyone else who has been burnt by the belief that it’s worth standing for something, the more they find something in common with the rest of us suckers.

That empathy is the way out, as offered by Yakuza. The series never attempts to reconcile or sugarcoat how doomed or ridiculous Kiryu or Majima’s quixotic quests to maintain their phantom ideals in a world never set up for them is. Neither is ever truly successful in changing the world for the better in the way they want to. In the end, the Yakuza are the Yakuza. But they also remain themselves, in spite of it all.

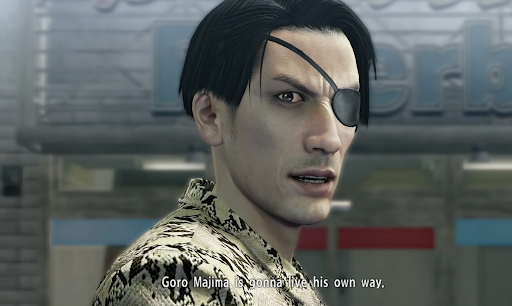

At the end of Yakuza 0, Majima chooses to affect the wild personality we’re become familiar with in the other games. As Yakuza 0 reveals, it’s a conscious choice on his part: “My mind’s made up. Right, wrong… nobody knows what the difference is in this town. So I’m going to have more fun and live crazier than any of ’em.” Of course, his version of “living crazier” is carefully protecting Kiryu’s virtuous lifestyle in his own way, like a psychotic catcher in the rye. It’s a hardwon resolution that winds up not being so different from what he did with the women of Club Sunshine.

Because, after all, we can’t escape who we are. This is the “way out” of the endless disillusion cycle offered by Yakuza 0‘s cute little dress-up game and the entire series itself: yes, you were manipulated into becoming the person you have become. Yes, the only reason you were taught to believe in those things in the first place was to manipulate you. Yes, your allegiance to those beliefs makes you susceptible to further manipulation. And yes, as long as you cling to any version of what you want to believe about yourself or the world, you stand to be manipulated and see your efforts turned against you. None of that means you have to give those things up.

Ridiculous little Club Sunshine can become the #1 club in Sotenbori. Ridiculous, honorable men like Kiryu and Majima can exist in an immoral world of hardened criminals. We can make room for what we want, no matter what they try to tell us. We can *make* our version of the way things should be true, even if it’s based on something that was only made for profit. We just need to give it to each other—and perhaps go a little crazy in the process.

Harry Mackin is a semi-retired freelance videogame critic and full-time sellout. He also has two podcasts, Trylove and Stoop Kidz, neither of which are about videogames (they always said if you want to make it as a games writer, you should have interests other than videogames, after all). You can follow him on twitter, too, if you’re so inclined, but he can’t make any guarantees as to the quality of the experience.