Let’s Play a Love Game: Love Across the Fourth Wall

Eric Cline breaks walls and wins hearts.

Conceptually and historically, 2013’s Namco High is an oddity. Players assume the role of Cousin (specifically cousin to The Prince from the Katamari series) as they strive to find love amongst the titular Namco High’s student body. The majority of students are characters from various Bandai Namco titles, most famously the ship from Galaga. There are also a handful of characters from Homestuck, a fact that feels less random when one learns the game’s director is Homestuck creator Andrew Hussie themself. The browser-based dating sim lasted barely over half a year before developer ShiftyLook’s dissolution, relegating its existence to archival status via the likes of old Let’s Play videos and inclusion in the Unofficial Homestuck Collection. The game is as silly as it sounds, and it often uses meta commentary that draws attention to the fact that it is, in fact, a game. Ironically it’s these self-referential portions of Namco High that most speak to real world concerns, in my case the fear of death.

The game begins with Cousin in detention alongside eighteen potential romantic partners. Players have the option to talk to all said characters in this opening scene without having to commit to any route in particular, and Davesprite makes by far the most bewildering first impression. He immediately tells Cousin that this opening interaction is irrelevant to the game’s progression and only exists to provide a taste of what’s in store. While Cousin is free to pursue any fellow student they choose, Davesprite is not just yet another potential boyfriend but also uniquely able to provide advice and tips as a sort of guide to the game they reside within. Cousin, unaware of the fourth wall, initially views Davesprite as an unintelligible weirdo.

I tend not to enjoy fourth-wall-breaking media. Whether it’s a matter of over-exposure or just personal taste, I don’t tend to find anything humorous about a character looking straight at the camera, saying something to the effect of “This isn’t real,” and winking. (Consider that just one of many reasons I’m not a Deadpool fan.) In order for such commentary to work for me, it has to do just that: commentate, not simply present the acknowledgement of artifice as humor in and of itself.

Fortunately, while Davesprite does get meta for humorous purposes, the game also utilizes said metanarrative to deepen his character and raise interesting philosophical questions. The first question is the obvious one non-Homestuck fans will have about the character: who is he? Aesthetically, he looks like an orange young man with wings but no legs, floating with a body that just sort of trails off in a spectral tail beneath his torso. Part-bird, bird-ghost, and part-boy, it’s a design that’s practically tailor-made to make players think “What the fuck?” (And, if you’re like me, follow up with a “That’s pretty cool.”)

To both Cousin and the game’s benefit, Davesprite never recites a fandom Wiki paragraph explaining what events in his source material led to the creation of such a strange being. The specifics of time travel, game constructs influencing reality, and all around confusion in Homestuck are convoluted, and largely insignificant compared to what Hussie thematically strives to do with them. The CliffsNotes are as such: Davesprite is sort of undead, but also sort of a clone of an original Dave (one of Homestuck’s protagonists), and in both Namco High and Homestuck proper is privy to critical information that helps him aid others in their quests. He is not omniscient, nor is he a Copy-Paste of the original Dave. There are clear personality differences spurred on by their different life experiences, even beyond the obvious base reality of their simply not being the same person.

With all that said Davesprite is very self-conscious about his status as a “real” person. Even in Homestuck proper, he had to contend with other characters disregarding him due to his not being the “real” Dave, regardless of the fact that he still existed alongside them and had thoughts and feelings of his own. Within the context of Namco High, his emotional state has further deteriorated. Removed from his original world, he no longer knows if he has any role truly worth fulfilling. Burdened with the knowledge that the events surrounding him take place within the confines of a game, he’s come to lack any belief or confidence in the notion of free will. His choices, and those of Cousin, seem inevitable; their romance, a foregone conclusion robbed of full agency on their parts.

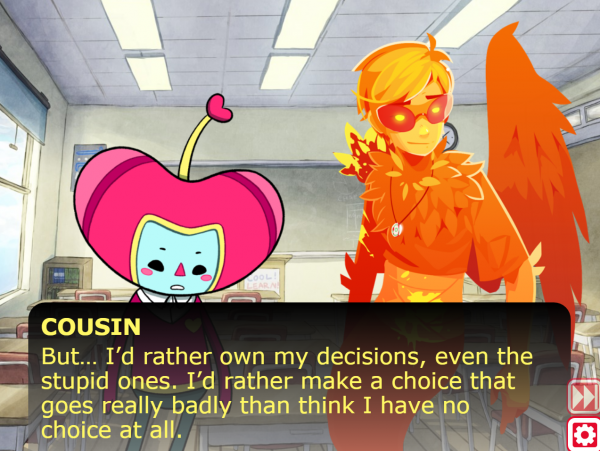

It’s a gutsy premise, and not one that can be wrapped up satisfactorily with a mere rebuttal. While Cousin initially refutes Davesprite’s claims about their status as game characters, it wouldn’t be enough for him to remain steadfast in his disbelief. The player, after all, knows the truth. What matters, then, is what Davesprite and Cousin do with the limited portions of truth they’re privy to.

After first meeting in detention, Cousin and Davesprite engage in some typical romance game bonding: first they take part in a club together (specifically the Webcomics club, providing fodder for more meta acknowledgement of Homestuck and Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff), then they eat lunch together atop the school where Cousin gifts Davesprite some delectable birdseed. They both have fun and Cousin enjoys getting to learn more about Davesprite, but tension mounts as Davesprite keeps up his meta schtick. Cousin is willing to give Davesprite the benefit of the doubt with regards to their existence being confined to a game, but refuses to agree that their actions are predetermined. Cousin believes it’s important to take ownership of his own choices, regardless of how they may play out.

Cousin holds this conviction strongly, and acts on it in the game’s final scenes. Pac-Man gets kidnapped, and rather than trust in Davesprite’s assertions that everything will work out regardless of what they personally do, Cousin believes it’s important to take action himself. The people he cares about are important, and it’s important to fight for them regardless of how “real” they may or may not be. Ultimately, Davesprite opts to fight alongside him, having come to a similar conclusion: that he can define what importance means to him, and that he wants to do right by the peer he’s come to feel such affection for, predestined or not.

In simplest terms, Cousin and Davesprite decide that it doesn’t matter if they’re real or just characters within some larger game. There is of course the axiom that striving for what one wants or believes in is worth doing regardless of if success is ultimately achieved. Beyond just that however, the pair’s uncertainty about their future rings true to home. Upon saving Pac-Man and reaching the game’s conclusion, Cousin asks Davesprite what comes next. Now lacking answers, Davesprite remarks that he doesn’t know and he had avoided raising the question because he didn’t want Cousin to get scared.

It’s this ignorance about the future that most spoke to me about the game right when I needed to hear it. Death and the uncertainty of an afterlife have always been terrifying topics to me, and they’ve been especially on my mind as of late. Cousin and Davesprite are faced with the same question as the screen begins to fade to white, but rather than spend their last moments terrified they choose to take solace in each other’s presence. All they can trust in is the here and now, and how thankful they are for the time they spent together– time that was a choice in and of itself, given that Davesprite is just one of the many romanceable characters in the game.

Though it gleefully acknowledges its status as a work of fiction, Namco High avoids the pitfalls of shallow meta commentary by inviting the player to consider the similarities between the game world and their own. The point is not the acknowledgement of artifice, but the blurring of any meaningful distinction from the real. On one level, Davesprite’s worries about his and Cousin’s lack of agency are well-founded. The pair are in fact video game characters, and their romance can only end in one way. Nonetheless, this doesn’t separate them in any real way from the player experiencing the story. I am every bit as ignorant about the circumstances of my fate post-death as Cousin and Davesprite are, if not more so. Though I perceive myself as “real” I possess no means of proving that I am not similarly a construct bound by some creator’s whims with regards to my choices. Regardless, I take ownership of those choices because they are, in every way that matters, mine.

After the credits roll, players are treated to one last image of Cousin and Davesprite holding hands as they approach a white door-shaped light, a representation of death, further life, the unknown, and the sheer joy of what has thus far passed. If a pair of immaterial constructs can keep their composure in the face of such real fear, then maybe I can try to as well.

Eric Cline is a writer, editor, and podcaster. Besides being a columnist for Haywire Magazine he also co-hosts the comic book appreciation podcast Chris and Eric’s Longbox Adventure. His Twitter is @ZorakRichardson.