Let’s Place: Three Stories of Witnessing the Impossible

Daria Kalugina wanders empty spaces.

On April 26, 1986, the explosion of reactor №4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant set off the implosion of the state, and left behind the abandoned territory, now slowly being reclaimed by nature.

I remember a PE lesson sometime in the early 2000s where instead of exercises, we spent two days being told what to do in the event of a nuclear explosion. We were sitting in the auditorium where the lights were always a bit dimmed. I don’t know whether it was the ghosts of the Cold War haunting our teacher personally, or was it the lessons of Chernobyl included in the school program, but this reconstructed fear stuck with me for a long time since.

In the wake of HBO’s new miniseries Chernobyl, I wanted to explore three narratives of events incomprehensible to the human mind. The ones that dive into the scenarios (real or fictional) that in different ways push one’s mind to meet the limits of its existence. Stories of impossible witnesses and witnessing the impossible.

A story of extraction: The Leftovers

I’ll start with another HBO title: The Leftovers is a series based on the book by Tom Perrotta. The story is centered around the aftermath and mental fallout of the “sudden departure” – the sudden disappearance of millions of people around the world, instantaneously and without a trace, leaving behind their loved ones. Two percent of the world’s population, gone to nowhere. In that moment, the world as we know it ends, the common and familiar are no more. Those left behind try to reinvent themselves in this imposed new state of being, and must bear the subsequent search for reasons and ways to cope. The personal loss dismantles the whole world.

“We are living reminders,” says the motto of Guilty Remnant, a cult-like community who deprive themselves of speech and their lifestyles from before the event. They wear white and smoke constantly, shortening their time on Earth and not letting others forget. They reduce themselves to this sole purpose, radically embracing the new distorted world.

…

People leave their homes against their will, they are disappeared into nowhere, leaving behind painful memories.

Communities are shattered and reformed, and a sense of togetherness seems impossible due to severe trauma.

Abandoned by some, the suddenly defamiliarized world is inhabited in a new way, in the wake of this grief without closure.

Communication has to be reshaped – whether it is a communication with the departed or between those who remain.

Remembrance becomes a wound.

In the search for an explanation, traces of radiation are found in the places where people disappeared, yet faith in science is compromised as the line to the supernatural is blurred, and multiple beliefs are flourishing in the search for an explanation. One’s mind wanders, finding refuge in religion and spiritual practices, and the question perpetuates: was it rapture that annihilated the world?

A story of extinction: Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture

In this 2014 piece on Gamasutra, Dan Pinchbeck recalls the looming post cold-war anxiety and threat of a nuclear action that he felt during the 1980s – this fear vibrates throughout the twisted serenity of the abandoned village in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

As with many walking simulators, we play as an unnamed traveling gaze. The identity of this spectral viewer resonates with the world they witness: in this world devoid of humans, the only actor we see is a mysterious traveling light, that if followed unveils the stories of people it vanished, reenacted by human-shaped projections. In a way, not having a body keeps us safe from the danger.

EGTTR opens with a shot of a landscape full of green and flowers. The unsettling rural serenity of a depopulated village is one of the key visuals of the game. It begins with the end: the aftermath of the event that wiped out humanity completely.

Walking around the village we find blood stains and other left-behind traces of human life. We see peoples’ stories unfold in the shimmers of human-shaped light, as if stuck between two mirrors they endlessly reenact the stories of their entangled lives. We get to know about the relationships they had, and frustrations they felt. We learn somebody tried to stop the light, and how others were trying to establish communication with the entity to reason with it.

…

People left their homes against their will, they were taken away, leaving behind the implicit trace of something horrible that happened to them.

Togetherness, fleeting in the world before the event, could it be now found the life after?

Communication is hijacked by the entity, as it learns to spread via landline.

The place they left behind hasn’t yet been claimed by nature.

Once inhabited by humans living closely together, the abandoned village has become the realm of objects, witnesses of the old life.

Religious conjectures are fully explained by the nature of meeting another form of life. The magic is dispelled by science.

One’s mind survives the headache of the encounter, reshaping itself into a completely new form of existence, as the light cast by people disturbs the uncanny landscape.

Aside from motionless objects, our only witness still living is nature, plants and greens that remember the event and the world before it. Devoid of humans, the unnamed gaze witnesses the end of the world, where all that is left is light, and the unruly flowers.

A story of evacuation: Chernobyl Herbarium

While the HBO series reintroduces the accounts of witnesses entangled in the choir of Chernobyl’s oral history, the 2016 book Chernobyl Herbarium: Fragments of an Exploded Consciousness by Michael Marder and Anaïs Tondeur instead directs its attention to the nature caught in this man-made disaster. “This book is dedicated to the earth, animals, water, people, air, and plants who (or that) have suffered as a result of the Chernobyl catastrophe.” The consequences of the event are hard to fully trace. An invisible, yet very real danger claimed these spaces, those lives and this world.

The blast contaminated nature so that it became hostile to humans, presenting them with an invisible, unthinkable threat: every creature, entity and object became dangerous and unfamiliar. Likewise, humans turned on nature, leaving behind pets and crops. In this fight inhuman witnesses became the subject of “liquidation”, to the point where even the soil itself was buried.

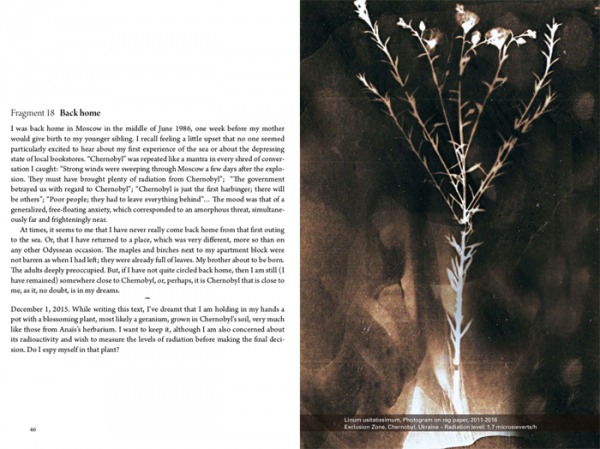

The artwork by Anaïs Tondeur featured in Chernobyl Herbarium consists of a series of photograms made with plants from Chernobyl. Plants that were absorbing radiation in the same way they absorbed sunlight. The photogram itself is like a witness account of the object: there are no lenses, there is no manipulation, only the object, light and photo-sensitive paper. This is how the invisible is translated, and the document becomes a witness.

…

People left their homes against their will, on the premise of temporary evacuation, leaving behind their belongings, pets and domesticated animals. Their homes became uninhabitable, before it became abandoned.

The sense of belonging is distorted, communities are disturbed: people who relocated away from the fog of nuclear disaster carried the traces of radiation with them wherever they went, often ending up rejected or feared. Their witnessing itself became the threat.

Communication is distorted in the uncontrolled burn of the aftermath. Landline connections are wiretapped and correspondence is suspended.

The widened gap between what we would like to believe about technology and the reality of it has shattered faith in the peaceful atom. Obedient belief in science morphed into superstitions, negations. Some saw the root of all evil in radiation, while others ignored the warnings, picking fruits from contaminated territories – all because of this impossibility to conceive of something that lurks out of sight, escaping the grips of understanding.

One’s mind struggles to survive with its consciousness exploded.

One experiences the loss of a world.

In the 30 years since, the abandoned territory has been reclaimed by animals and plants, taken over by nature.

…

All three stories in various degrees concern the creation of uninhabitable spaces. Some are too dangerous to venture into, while others are lost in memory. These places are taken over by that uncanny threat hiding in the familiarity. The danger that gains its own agency – sometimes it outlives humans completely, sometimes they learn to coexist. And what accompanies it is the demand to witness that which is slipping away.

In response to that demand, Belarus now organizes guided tours to the exclusion zone, following the safest possible path through still dangerous grounds. What can one find there among abandoned homes?

From absence emerged the presence of something else, the gaps between what we know and what we believe gave to birth this new entity, embodied unknown, that comes in various forms through various experiences. The sudden fracture of our consciousness poses the question of what we can learn from it, how we can coexist, and how to survive when there will be nowhere to escape.

Daria Kalugina lives in Moscow. Sometimes she works in artistic education, and dreams of building fictional worlds for learning.