Let’s Place: Abundance

Daria Kalugina has it all.

The Need

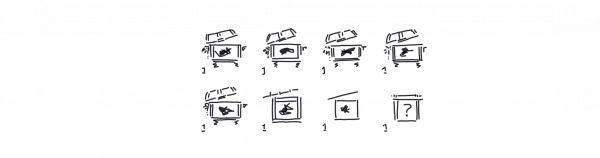

In the beginning I have so little.

A couple of essentials and some empty space to fill in with stuff.

As I progress through the game and learn new abilities, I acquire new things: things to collect, to trade, to craft with.

As I climb higher on the skill trees, I learn to travel with more stuff, extend the space of my inventory.

I learn to use more things, tools for my survival, things I didn’t think I needed in the beginning now become essentials as well. Others, with some elusive value invested in them, I will just keep in a stash, in case I find a use for them later.

But at some point it all becomes too much.

The Greed

I have too many games. Too many of them I haven’t played even once. They were acquired as a surplus, as a bonus of a membership. As a perk. As a freebie. Others were mass bought during sales. The only reason behind their acquisition was that I might eventually need them some day.

In the games I actually played, over the time I acquired too many resources.

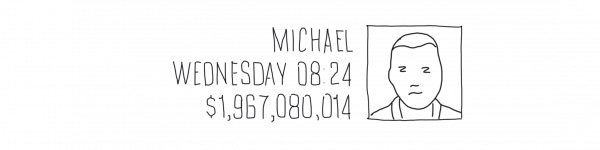

Money I will not spend.

In what timeline it is even possible to spend this much?

Too many changes of clothes, when in reality I just use one for stats, and one for show.

Too many ingredients for potions I won’t brew.

The random junk I hold onto just in case.

Possessed by this need for possession I keep collecting stuff I don’t need. It’s easy, it’s accessible, it’s there. It can be easily converted, crafted, traded for the item with better traits, or just simply sold for in-game money.

But do I really need this money? And since there isn’t much I can do with it, except trade, spend or simply keep it, I find myself stuck in the endless cycle of pointless exchange. I keep collecting stuff, worthless valuables.

In what timeline it is even possible to spend this much?

In what timeline it is even possible to spend this much in a game, when I keep using the same three tools over and over.

At some point the thought sparks in the back of my head: what if I really owned this much?

The burden of abundance

At times it feels like I can have it all: maintain this nomadic, sometimes survivalist lifestyle, while having this bottomless backpack always at my disposal; or even having some mansion, a lair filled with clothes, health regaining items, weapons, or whatever.

What it is to own something in a game?

What it is to own a game?

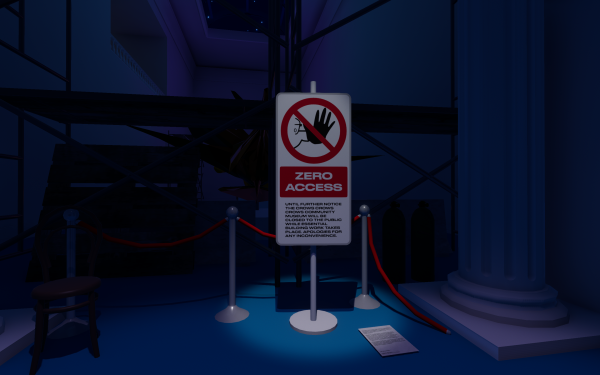

In 2018 Crows Crows Crows published the Crows Crows Crows Community Museum, a virtual exhibit of works from their Discord community. Some time later, CCC announced in their fabulous newsletter the Museum’s update. With that update the museum was now closed for public (players).

Thanks to my compulsive back-ups I now own two versions of the museum – one is open, and the recent one is closed. My excessive ownership disrupts the timeline CCC intended for its Community Museum.

It’s easier with discs: although I don’t have many, I can trade them or sell them easily. The monetary value of the physical object fluctuates, serving as a kind of a capital I can operate with. And even if the game may gradually lose its value over time, or otherwise gain it as a limited edition commodity, these processes come as almost natural at this point.

When I buy digital copies, or even access games through subscription services, then my ownership becomes more contested. Sometimes it feels more like I’m renting, or gaining the privilege of accessing games from its rightful owner – I’ll lose a major chunk of my library if I cancel my subscription, or if the service dies altogether. Which brings up other issues: one is that my collection of games is mostly curated by the platform itself and market driven reasoning to make a particular game free this month. In this way I lose control of my possessions, as I’m getting used to acquire new games on the premise of making use of them someday, not today. Similar to bingeing random titles on Netflix only to get some use out of my subscription. But unlike Netflix, my stack of digital copies is buried in the bottomless inventory of my account with a silly name I picked ages ago. This is the capital that doesn’t work, neither for me nor anybody else. And it becomes overwhelming to even own it. The thought of a timeline in which it’s possible to play this entire catalog of games makes me nervous, and I retreat to some familiar titles instead.

Another effect of the subscription deal is that the longer I maintain it, the more I get, and the more I lose upon cancellation. At first glance it looks as if my collection gains more and more value, but in reality the opposite is true: my collection of digital games grows older and less interesting with time, and all the while the growing heap of titles I won’t ever find time to play only gets bigger. So what happens next? Do I acquire the parts of the elusive global game archive curated by the market? Or have my game savings become the investments? Never to be played, but kept safe for the day I might need them?

Owning things within games — ever escaping possession

When I collect loads of stuff in the invisible bottomless inventory I don’t feel it’s a bad thing, although in reality it may considered hoarding.

Here I don’t talk about things like borderline gambling through loot boxes, or trading expensive and rare skins, but rather the usual in-game resources that can’t be turned into profit outside a game world. There are only a few options of what I can do with the things I have in a game, and even fewer ways to establish an alternative relationship with the resource. The things I carry do no good to anybody: most of the time I can’t donate them to other players, nor NPCs. I accelerate from collecting vital items to piling up things I don’t need really fast.

I collect things and abilities to the point it doesn’t matter anymore.

Once scarce resources are now plentiful. And that’s a problem. As there is no value in the in-game things anymore, there is no assurance that my actions still hold meaning. Although this easy earning can bring pleasure, and a false feeling of possession yields satisfaction, my navigation is numbed by the overflowing of this “wealth.” The profusion I’ll eventually earn by default.

In a regular sidequest I met somebody in need, and I have a gracious option to waive the payment for my errand, so they could put this sum to use elsewhere. Although this option is treated like a sacrifice, it’s not like it cost me anything. I already have too much.

Devaluation

With the deflation of the resource comes the devaluation of relations. The man who delivers, Sam Porter Bridges, gets visibly overburdened with cargo when it exceeds his current physical capacity. Being the essential agent of exchange, and holding the logistics of the whole remaining world together, he acquires the recourse impossible to spend: the likes I can’t spend, trade or put to any use. It’s only value is in the process of its acquisition.

He transfers goods of versatile values, in the identical metal boxes – from rare collectibles from the life before the cataclysm, to hot pizza and medicine or supplies necessary for survival. Items equated by the indifferent logistics that came to replace crumbled politics. Being the essential agent of exchange Sam is a man with no needs. But this is not that liberating riddance of needs and possessions. Although distorted by devaluation of goods and labour, the relations itself become a resource.

Within Death Stranding I landed in the world of post-apocalyptic plentitude. But instead of hoarding digital objects, I never run out of stuff to get rid of.

Daria Kalugina lives in Moscow. Sometimes she works in artistic education, and dreams of building fictional worlds for learning.