Let’s Place: A Play in No Acts

Daria Kalugina has a job as a Bob.

“To deliver a powerful game performance, you must humanize a digital puppet made of polygons and textures. In a sense the actor plays the surrogate for their audience, they are entry points into the game’s world and personalities.”— Rosa Salazar and Christoph Waltz, introducing the Best Performance nomination at The Game Awards 2018.

This is 2005 and this is David. He is a writer and director of Fahrenheit. He introduces me to his friend Bob. Bob is a crash test dummy. David invites me to control Bob, showing me what he can and can’t do. It’s weird to see David and Bob together, in the end David was the one who made Bob, he made him for me to learn to play. So here I am, watching them together, on the other side of the screen. Even though I know David is a real human, I’m connected to Bob more. I’m supposed to be Bob, Bob is supposed to be me.

When David gives me the controls to Bob, he is now controlling me a bit, while I’m repeating (reenacting) the actions, scripted by him, performed by Bob, in the world designed by David’s studio. Same story told from different perspective: author, player, character. Employer, consumer, worker. A worker, a worker and another worker.

Bob is irrelevant.

Characters:

AUTHORS, designers. The ones who design the space with its physics and laws, where the narrative is unfolding. Ones who build the decorations. Ones who lighten the decorations up. Ones who design, ones who produce, ones who test — workers.

ACTORS, who perform. Who donate their body to be re-enacted later. Who donate their voices, mimics, movements dissected in parts, sliced as a combination of dots in space. As the relations between those dots. Workers. Scanned faces attached to new bodies. Collective bodies, imagined bodies. Assets?

WRITERS, script-writers, who work to adapt the performance, who script the performance and then script how you will perform it again. And also other writers, who write about scripts, who write about performance. Writers, code-writers — workers.

SPECTATORS, who watch players, who watch actors, who subscribe. Who narrate while watching; who produce their own script, or just silently there.

CHARACTERS, who can’t go off-script, yet sometimes do. Animated by many, they are individuals that hide a collective.

PLAYERS, you, me, our friends, our strangers, professionals. We who require attention, we who require inclusion, we who require representation. Who donate our time to perform someone’s story. Who inherit the actors’ performance, author’s story, some else’s story. Does it make it our story?

The ones who show themselves playing. The ones who watch others playing. Playing for fun, and playing for a living. All workers.

***

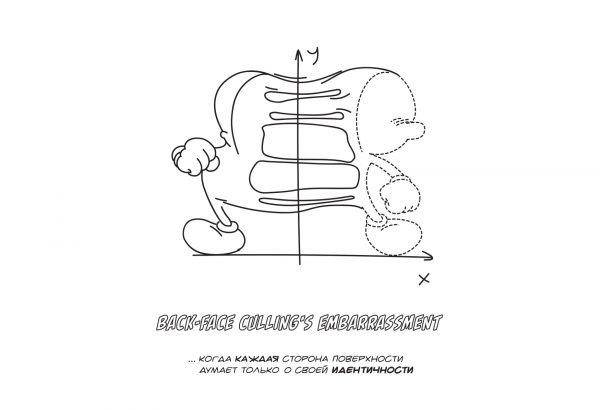

“The Birth of Asset”, Sara Culmann, 2018

Caption reads, “…when every side of the surface thinks only about its identity”

Characters are controlled by Players, scripted by Authors.

Players are controlled by Characters, restricted by their stories, limited by the mechanics. Players are controlled by Authors, they are watched by Authors, they are watched by the subscribers. Actors are watched by cameras, players are watched by Kinect. Authors are watched by Players. Judged by Players? Judged by consumers, judged by workers. Are authors controlled by Players?

Detached from the authors by origin, characters foreclose the multitude within.

Detached and reinstated in another time, in another space. Absorbing multitudes. Reacting to the context. Tales of recursive controls.

Controlling the characters, do players become authors? Controlling the players, do authors become players?

***

Some time later, somewhere else

Bob is a fighter. He keeps surviving a crash. He keeps surviving a crunch. And while doing so, he is also becoming someone else. He was irrelevant, he was alone. He was a dummy, a placeholder for another Bob to come. Performed by a multitude of agents, now he is more detailed, more human(?). He still responds to your lead, yet now there is the friction, between who you are and who Bob is. Who he was performed by, who does he consist of. Bob is their own person(?), despite being the product of shared labor. Bob has their own story, with their own agency re-constructed piece by piece.

And despite this, I still feel like I am Bob, even as I know I am not.

I knew he was going to die. Everything was pointing at it. And even though I didn’t have a chance to distance myself. Given some minimal choice I played as I would act in real life. And when he died, I took it hard. I found myself alone and confused. Confused as I lost my self a little bit in the act. I wonder, what did the actor feel? What did the designer feel? The tester? Developer? Writer? Crash test dummies sacrifice themselves for the sake of human’s safety, they go somewhere where humans can’t. Similarly, actors — everyone involved in the construction of a game, and its characters — present the entry points not only to game worlds, but also to the limits of what we can experience as humans.

Daria Kalugina lives in Moscow. Sometimes she works in artistic education, and dreams of building fictional worlds for learning.