Embracing the Incomprehensible in Hylics

Heather Alexandra finds contentment in Mason Lindroth’s bizarre take on RPGs.

I die for the third time. I watched my bones crumble and my face melt before awakening in an afterlife populated by flopping fish. Walking over to the dispenser, I deposit pounds of meat in exchange for Flesh. One of the fish tells me that the executive lounge is open to those who’ve died at least three times. I qualify. The lounge is nothing but a small balcony populated by a writhing lump of unknowable gender and a water cooler from ages past. I fill up a paper cup I found at the top of the mountain, its location first revealed to me by a churning machine that made me dream of the realm where I also found the Sage of Brains. I activate a crystal and warp back to reality. Or whatever passes for reality.

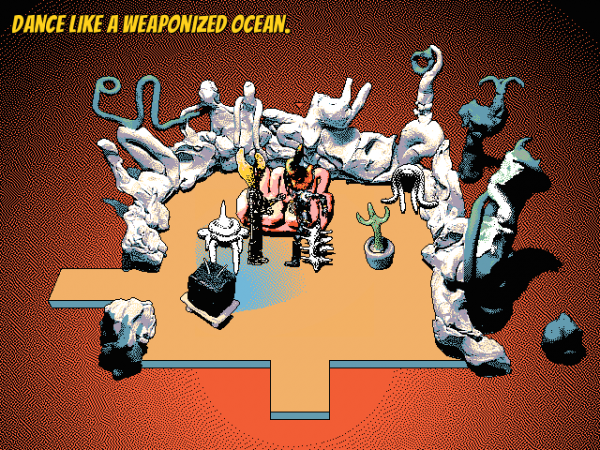

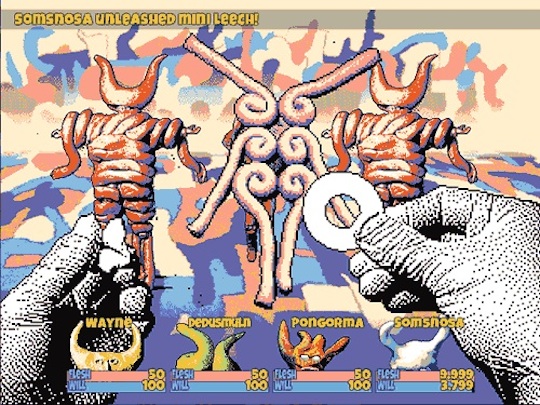

Such is the experience of Mason Lindroth’s perplexing and madcap RPG Hylics, a vague tale concerning a nobody named Wayne and a crew of misfits as they quest to defeat Gibby, King of the Moon. The entire affair feels like someone tossed Gumby, Earthbound, Salvador Dalí, and Yves Tanguy into a blender, sprinkled some Terry Gilliam into the mixture, and watered it down with liquid LSD. It is an experience both mystifying and completely alienating; nothing makes sense but everything is beautiful. It has the approachable systems of any JRPG but contorts them towards nearly farcical ends. Everything demands inspection while promising confusion. You’ll take the toilet paper from your restroom to wear as armor, toss space shurikens and frozen burritos at enemies, and dual wield a fork alongside your battle axe. Hylics is a game enamored with the absurdity of games.

There is only one understandable and safe space within Hylics: the menu. Removed from the traditional game space, it contains all the usual RPG engagements. Options like Things, Powers, and Get Dressed all have easily understandable and translatable counterparts: Items, Abilities, Equipment. Interpretation is easy, unlike everywhere else. It is also the only place where there’s any real explanation or aid. That warm burrito I found in my toilet? I’m very politely told that it revives a dead ally and restores 50% of my health. If I am unsure about how to equip myself, I can simply select Optimize and the game ruffles through my collections of garbage can lids, parasitic crystals, cellophane strips, and demon skulls to do it for me. The menu is the one space of explicit comprehension.

Any remaining understanding comes from recognizing borrowed formal elements. Hylics is an RPG at heart, and therefore a player familiar with genre conventions and structures can parse out something resembling coherence or, at the very least, create connections between vaguely familiar elements in order to make the space approachable. This is an automatic process that occurs while playing any game, but it is more apparent here, where the logical leaps are, if not larger, at least more observable. I am unsure how often players are aware of just how much they reap the benefits of accrued years playing games; just offering the controller to a neophyte can express how much of an accessibility problem games can have. Hylics’ absurdity forces the player to pull upon these assumptions in order to perform and highlights these biases in the process. Games rely heavily on pattern recognition for their accessibility, and Hylics contains just enough patterns to provide some grounding. While it is hard to speak towards Lindroth’s intentions, the end result is not unlike looking through a funhouse mirror. You know the real image but see the inherent absurdity of the reflection.

This grounding is important because the rest of the affair is so brazenly Dada in its opposition to what we might consider the gaming bourgeois: economically comfortable consumers of AAA titles. Nowhere is this more clear than in how the game handles dialog and text. NPC text is, with few exceptions, generated procedurally through a highly randomizing script. “Someone embraces another corporeal prison. And corrosion manifest’d another mandible,” you might be told. The next time, someone might ask you what sustains your zesty beast. The results are anti-interactions, points in time where words lose their fundamental meaning and language breaks down into little more than sounds. It might be the only time I’ve seen my mother tongue turn truly incoherent. Hylics stands contraposed to the mainstream. The bizarre interactions provide a strange ludic and narrative apprehension that can be painful and arresting, pushing against presumed ideas regarding play that almost assuredly would make it a frustrating or exasperating affair for a traditional “gamer.”

Yet, within this isolation and confusion, there is a lot of beauty to the found. The aforementioned anxiety is merely a byproduct that comes from realizing your freedom as an actor within Hylics’ space. If there are no particular rules or comprehensibility, you’re free to converse with the game in a wonderfully loose boogie that embraces the anarchy. Up is left, down is a banana, yes mean fish, and meat is precious. While there may be some way to suss out patterns to the dance, the most important thing is to dance with unabashed glee. By the end of it all, I could only think of Friedrich Schlegel:

“…Is incomprehensibility really something so unmitigatedly evil? Methinks the salvation of families and nations rests upon it…Verily, it would fare badly with you if, as you demand, the whole world were ever to become comprehensive in earnest.”

Heather Alexandra is a freelance writer and critic. Her work has been featured at Paste Magazine, Kotaku, FemHype, and more. Additional works can be found at TransGamerThoughts. She once gave the President a high five and thinks you look lovely today.