Due Diligence: Spooky Territory

Leigh Harrison doesn’t need to ask for directions.

Regular readers (hi mum) will probably remember I had some conflicting opinions about Firewatch. One of the things I particularly appreciated, however, was its use of a physical map, something I’ve gushed about in years past when discussing Far Cry 2. Having my character hold up a real map, instead of me looking at my own digital one in a menu, firmly anchors us both in the world and gives our movements more weight. I also find myself more connected to my surroundings, because physical game maps tend to look more like real world ones—with contour lines, waypoints, et. al.—so I’m more inclined to use a combination of spatial awareness and map than just blindly follow whatever GPS-style line I’m given to walk on top of.

Still, both Firewatch and the hallowed Far Cry 2 don’t 100% invest in their orienteering, each choosing to paste your location onto their paper maps to ease navigation. I’m fine with this in all honesty, but have always been intrigued to experience a game built around map reading (there’s never a dull moment with me around). I was understandably excited, then, by the promise of Kholat, a game that is indeed, at least from the outset, all about reading maps.

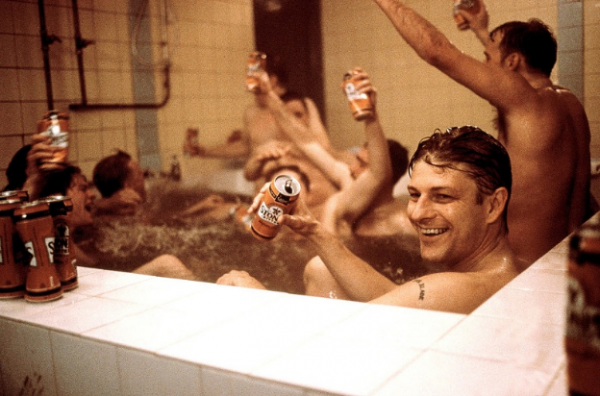

I won’t lie, I was also attracted by the game’s impressive back of the box description, which proudly states it is working with only the finest clay. “Narrated by one of the most popular British actors, Sean Bean, and powered by Unreal Engine 4, Kholat is an exploration adventure game with elements of horror.” I’m not too fussed about pretty graphics, and horror games need to be up there with Silent Hill 2 to have any sway with me, but Sean Bean, now that’s a different story. I’ve always been openly in love with the man—because that’s what he is: the manliest man’s man to ever exist. He’s like a butch Christ who’d grab that spear out of your unbelieving Roman hands, skewer you to a rock through your face, rip the nails out of his limbs with teeth, determination, and sweat, and then go home to smoke infinite cigarettes and drink infinite tins of Carling, all the time managing to nurture the growth of his namesake religion and convince the world he’s dead. He’ll never truly die, for that would be impossible.

Anyway, map reading. In Kholat you spend your whole time trudging around a mountainous wilderness. You’re there trying to make sense of the Dyatlov Pass incident, a process which involves walking about following a map. The game takes place an ambiguous period of time after the 1959 tragedy, which saw nine hikers perish in mysterious circumstances on the slopes of the titular Kholat Syakhl—the Dead Mountain. This particular use of “dead”, however, simply refers to a lack of fauna, rather than the place being eerie and malevolent. Not that this awkward truth has prevented a great number of outlandish conspiracy theories springing up around the event. Depending on who you listen to, the hikers were killed by aliens, or the government, or a madman, or a giant evil bear with opposable thumbs and a laser machete. They were not, under any circumstances, killed by hypothermia. Simplicity is boring, I suppose.

I began my investigation at a little campsite, and received no direction in the typical videogame sense. Instead, I was given very real world direction: a map, a compass, and some coordinates of special interest. Naturally, my first instinct was to consult these place markers, find the nearest one, and then figure out how to get there. Knowing that the top of a map is always orientated to north, and that the red bit of a compass points to the same place, it was fairly easy to at least know roughly which direction to head in. And so I did. And I reached the first coordinate in about two minutes.There, I was treated to a short ethereal vision of the dead hikers, all of whom were running scared from a spooky bright light in the sky (not a mecha-bear in sight, unfortunately). I also found the first of many diary extracts, which unsurprisingly all help one build up a better picture of the game’s story. I then repeated this process a further eight times—follow map, witness fragment of past, read document—and then the game ended.

I was a scout in a past life, so I actually really enjoy outdoor navigation. I’m not sure whether I was born with innate spatial reasoning skills, or if all the maps warped my mind with their unnerving, black magical ability to contain entire mountain ranges and cities in a bit of paper, but I’m fairly good at interpreting 2D depictions of 3D objects. I never found maps that hard, if I’m being honest, so I had no trouble with Kholat’s hands-off approach. I mean, it’s easy: figure out where you are—it helps to know your starting location, so pay attention from the get-go to avoid unnecessary disorientation—and then just, you know, take notice of where you’re walking rather than looking at your phone the whole time. That’s it: a two step process at best, one step for people who’ve left the comfort of a city a handful of times.

This last part is likely crucial to why almost every single review of Kholat makes mention of its fastidious approach to orienteering. Even in positive ones, writer after writer bemoaned how difficult they found navigating the game’s large, outdoor landmass without being expressly told where they were at all times. I find this sad, because, as we shall see in good time, the only genuinely interesting thing about Kholat is its more realistic take on map reading. It’s also worrying that we’re seeing entire generations of human adults who are unable to function without technological crutches. To remedy this crying shame, I’d personally suggest some form of programme or club teaching life skills and outdoorsmanship for all children aged between 5 and 18. Ah, right, that already exists. It’s called the Scout Movement, and only dorky kids like me are into that weird self preservation stuff. Yes, it might well be for “losers”, but you won’t find me dying on a mountainside anytime soon. No, I’ll safely make my way down and then go to the pub with Sean, where we’ll discuss survival techniques and rabbit gutting best practice over the finest lager money can buy.

If anything, I’d say the map reading aspects of Kholat aren’t involved enough. You can’t orientate your map in a direction of your choosing, which is something I always do when using one. It helps in creating a sense of parity between it and my surroundings, allowing me to better align the flat thing in my hand with the bumpy things all around me. The map in Kholat is also fairly impressionistic and doesn’t really give an easily readable facsimile of the area’s features. Elevation is conveyed through relief mapping (shading slopes and cliffs, basically) but isn’t detailed enough to give more than a basic representation of the mountainous terrain I’m surrounded by. Likewise, the paths it shows are more a guide than a given, with lots of smaller tracks ignored completely and the bigger ones sort of in the right place. These things all add up to make navigating the game’s large, mostly empty landscape more difficult than it should be, were its map mechanics that little bit more complex. This is the least of Kholat’s worries, though, because the rest of it, barring my always astounding friend Sean, is dross.

Much like my assertion about Firewatch, I don’t think Kholat seems convinced it’s interesting enough being purely about walking, and quickly begins to throw in numerous dangers to add that much needed “wow” factor. It’s ingenious and in no way annoying: the game is full of things that instantly kill you; perils which cannot even be avoided. There are the spike pits that are almost invisible underneath the snow that covers every inch of the entire game. Or the rockslides that similarly come out of nowhere. Then there are these ghostly apparitions who stalk certain locations. They make a mildly scary growling noise and your compass shakes when they come close. If they touch you you’re dead as well, so you have to run away from them.

Regardless of Kholat’s insistence that it’s a horror game, none of these things are remotely scary. In spite of clearly being designed to add excitement and tension, these pointless extra pressures do nothing to detract from the fact you’re still just walking—and sometimes running—around. In fact they drag it out even further, forcing you to retread the same ground repeatedly every time you instantly die, or jog about in circles trying to avoid one of the Slender Man–esque enemies.

I’m not really sure what to say past this, because I’m a bit flabbergasted, if I’m being honest. Which is worse: being boring or being mediocre? If it were just a really solid map reading simulator with added spooky visions, Kholat would be dull, sure, but at least it would have something a little interesting going for itself. It’d be a game squarely about reading a map, after all, and there aren’t too many of them just hanging around, are there? We have games about driving trucks, dating birds, farming, being the wind, chemical engineering, sibling love, and rummaging in cupboards, amongst other things, so why not reading a map?

Boredom is just as valid an emotional response as fear or excitement, but I worry that in games we still equate it to a simple absence of anything interesting. That Kholat is predominantly made up of quiet strolling shouldn’t be seen as a negative trait, especially given that when it does disrupt this emptiness it generally succeeds. The visions of the hikers you witness at the coordinate locations are always stunning, images of the group fleeing en-masse through woods pursued by giant orange death clouds a particularly atmospheric treat. Similarly, when the game goes for scripted horror over the Ever Present Boogeyman pursuit, it is genuinely spooky. Window shutters flapping in a gale, a ghost kid in a closet, a woman’s cries echoing around a cave; none of these things are particularly original, but when used to punctuate long sections of silence they are effectively unnerving.

But the game isn’t satisfied with its handful of standout moments. It wants to be YouTube fodder to be screamed over, rather than the slow burning, mildly unsettling experience it could—and should—be. Its most interesting aspect is not the artificial tension of being a few steps from death, but the surprise of telephone pylons suddenly bursting into flaming totems, the night sky turning blood red, and the clouds swirling violently around the moon as if they were a portal to Hell itself. This, after 20 minutes of walking up a mountain humming into the wind and looking at a piece of paper, is exciting. Boredom has the ability to accentuate and elevate the things around it, and in doing so becomes a perfectly valid tone in its own right.

I often wonder why so few games are brave enough to tackle the mundane; why there are hardly any works analogous to Common People, or Glengarry Glen Ross, or, as we’re talking about navigation, Deliverance. But then I read a load of reviews about a game sort of invested in pursuing the normal, the practical—the boring, and I see that games are still widely expected to be thrill rides, and if they fail in accomplishing this they fail entirely. Kholat isn’t allowed to simply be about overcoming the challenge of navigating a wilderness, and so it flounders as something it should never have been: a compromised, jumbled, and dissonant mess of other people’s ideas of what constitutes an acceptable videogame. I did indeed find myself lost in Kholat’s mountains, but not in the way I intended or hoped.

So go, you technology obsessed malcontents, and throw your phone in a river, buy a map, and have a long walk. Maybe if enough of you learn the joys of the great outdoors, when you finally do find your way back home Kholat 2 will be waiting, entirely based around a splendidly life-affirming hike from Manchester to Sheffield. It won’t need ghosts, or rockslides, or punji traps to keep you entertained, because you’ll finally be able to appreciate a jaunt through the hills accompanied by nothing more than the dulcet tones of the greatest man to have ever lived.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, makes DVDs for a living and owns a hamster. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.