Due Diligence: Not One Forgotten

Leigh Harrison (midshipman) was axed by an unknown attacker.

Wandering through the creaking decks of the Obra Dinn, I am struck by the quiet reverence of my task. As an insurance adjuster, I am ostensibly investigating the ghost ship to assess, catalogue, and cost out damages incurred. What is the price of sixty lives and a boatful of supplies, all lost somewhere off the coast of West Africa? But Lucas Pope’s games are never as removed as they first appear. As with Papers, Please, Return of the Obra Dinn may dress me in the uniform of dispassionate bureaucracy, but its main concern is helping me see the people underneath the admin.

When I was a kid, I loved reading obituaries. Every weekend I’d steal away to my room and pore over the weighty Sunday paper until I found them, hiding somewhere near the back. Even as a seven-year-old, I knew there was nothing morbid about marking the passing of a life. Obits are us at our best: work, accolades, spouses and progeny. Our every achievement laid out for all to read, only fully appreciable once no more can ever be written.

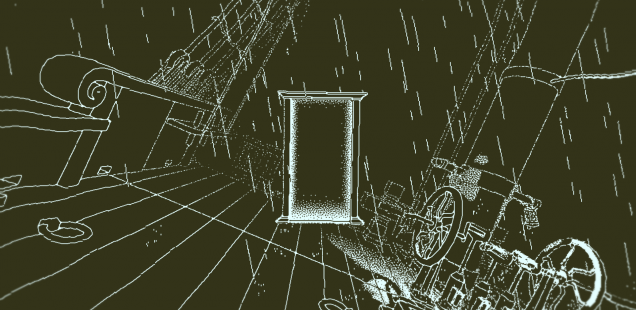

Obra Dinn is a game of obituaries in miniature. I pace the ship rationalizing circumstance and misfortune, my goal: to uncover the identity and fate of every lost soul on board. With a manifest and a couple of sketches of the crew, I must put faces and names to corpses, and explanations to deaths and disappearances. A magical pocket watch aids me in this, allowing me to witness each crew member’s moment of death. When opened near a body, it transports me into a life-size diorama of the incident accompanied by snippets of dialogue.

These scenes unlock in a defined progression, though out of narrative order. I might, for example, witness the aftermath of a murder in one, but only discover the perpetrator’s identity hours later, when shown another episode set moments earlier. Through carefully analyzing these individual vignettes, and cross-referencing them with my documents and their place in the wider timeline of events, I am assured I can arrive at the truth – namely, which deaths the company must pay for, and which it can write off.

My early deductions are made by simply following obvious fact. A dying man’s name is shouted by an onlooker, or his uniform identifies him. The bloke tending to the injured on three separate occasions is clearly the surgeon; the cook, the guy enthusiastically proposing he light up the grill. These answers, and thus these people, stand alone in the logic of the game’s grand mystery. They work and interact with their shipmates, but in being exceptional – insomuch as they are immediately identifiable – almost occupy space beside the wider crew, never feeling wholly part of it.

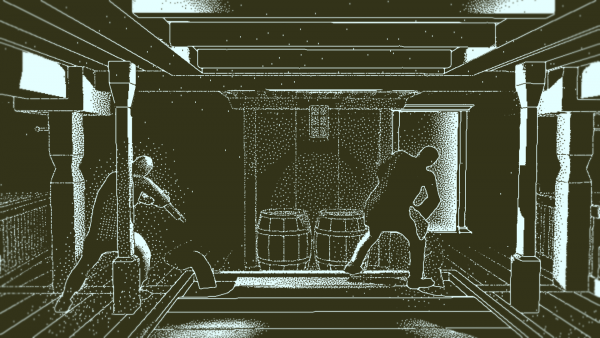

It is no coincidence that most of the easily-identified characters constitute the ship’s upper ranks. Almost all of the Obra Dinn’s officers and tradesmen are identified by the game’s midpoint; their importance within the social structure of the ship inversely proportional to their place in the puzzle. They are simply too obvious to pose much difficulty when their hats, British accents, and fancy uniforms single out their position. The lowly sailors, unknown in their ubiquity, are both the game’s narrative heart and its real conundrum.

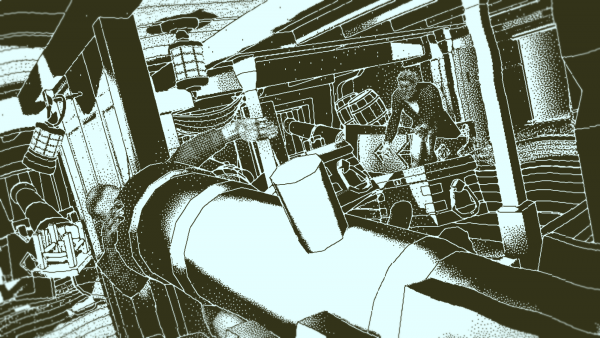

They are difficult to place because each is a bit player. The Obra Dinn’s downfall is brought about by the greed and disloyalty of its officers, who doom everyone else with little regard. And while the game’s narrative largely follows the tale of this small group, the nameless seamen on the periphery of every vignette are its true thematic and mechanical concern. They are effectively anonymous: no names uttered, no ceremonial garb. They are difficult to identify, and the only way to do so is through studying their interactions with each other.

I first see the tattooed man at the moment of his death, hewn in two yet still crawling – somehow, somewhere – across the deck. Later scenes, chronologically earlier in the story but given to me by the game out of order, chart his movements around the ship. He’s not the explicit focus in any of these dioramas, just somewhere off to the side while I’m being shown more noteworthy people. But his story is important. In six of his eight appearances, he’s fighting beside his shipmates to defend the Obra Dinn from its attackers. He’s never called out to nor speaks, just silently risks his life, sword in hand for those around him, until his luck runs out.

In his last scene, he’s finally identified. Shown working up the mast, it’s clear he’s a topman, part of the team in charge of the rigging and sails. Once I know this, it’s fairly simple to give him a name. He doesn’t look like his colleagues, who are all European or Asian, and so it’s a hop, skip and a process of elimination until I can tick the tattooed man off my list, jotting down his name, rank, nationality, and cause of death in my notebook. My adjuster’s notation may be coldly matter of fact, but alongside his identity, I also learn the truth of his heroism. When I file my report concluding the trading company’s insurance claims, I am sure to include this in my record of the Obra Dinn’s fateful last voyage, alongside tales of officer-led mutinies and high ranking cowardice.

The other topmen are Chinese, some are Irish, a couple English. As with the tattooed man, it is only through exploring their time on the ship, examining their interactions with those around them, that I can deduce their identities. Just like Papers, Please, class and race become key vectors of analysis. But in Obra Dinn this theme serves less as an indictment of institutional biases and more a celebration of diversity.

Papers, Please, which cast me as a poverty-stricken border agent, forced me to make snap decisions based on ethnicity and country of origin. By never giving me enough time or resources to adequately check passports, I’d approve or refuse passage based on sweeping generalizations about people and where they came from, just to meet my processing quota and earn a daily wage. If Kolechian dissidents were conducting bombings one week, it was easier to deny entry to all Kolechians than spend precious minutes looking over documents, trying to determine if each individual posed a legitimate threat. In Obra Dinn, I’m still compelled to use these same criteria – ethnicity, racial signifiers – to single characters out, but here it is to give them a name and purpose within the ship’s throng of faceless, unimportant workers.

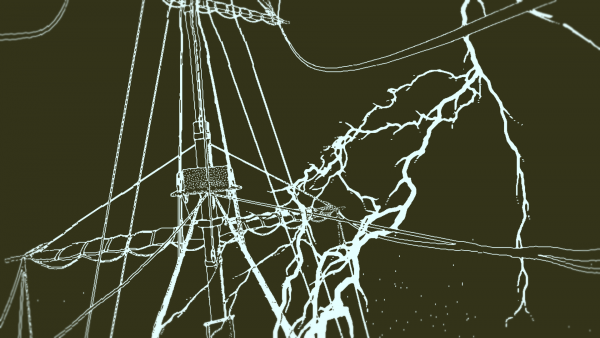

While different ethnic groups sit separately in my reference sketches, all drawn shortly after the Obra Dinn set out from England, this segregation doesn’t persist. Weeks, perhaps months into the voyage, everyone is thrown together, lurching as one, from catastrophe to calamity and back again. As the disparate crew mingles, their shared and divergent traits begin to belie their identities. A seaman with an Irish accent warns of oncoming danger, in the process letting on he’s Patrick O’Hagan – the only sailor from Ireland. Of the four Chinese topmen: by the time one is struck by lightning, I already know the names of two others and how they died, finally identifying their drowned friend. The anecdotes go on and on.

It’s racial profiling in many cases. But while similar techniques continue to be employed to generalize and excessively police certain communities, in Obra Dinn they are used to individualize. I can only know who these men are in relation to one another, and so their differences contextualize them, offering identities previously denied to the ship’s underclass. Fifteen nameless seamen become fifteen real people who lived and died aboard the Obra Dinn. With every deduction I write a new obituary, giving each hand his own story; carefully catalogued accounts of those thought unremarkable and beneath such reverence.

Return of the Obra Dinn, through its structure and nonlinear narrative, has me pay attention to these stories of everyday people. Just like Papers, Please, it is a tale of the downtrodden working class and their travails – be that, in this case, against class prejudice or the perils of a life at sea. But it offers a more optimistic take on this story, where sacrifice is seen and acknowledged and our differences are celebrated as being essential to understanding one another. The cowardly and duplicitous officers die early and obviously, leaving me time to ponder the themes of heroism and community that characterizes the Obra Dinn’s lower classes. Ultimately, there are no borders on the Obra Dinn, just people – but some are more people than others.

Leigh Harrison lives in London, and works in communications for a medical charity. He likes canals and rivers a great deal, and spends a lot of his time walking. He occasionally says things about videogames on the Internet, and other things on The Twitter.