Let’s Place: Collecting Things and Listening to Stories

Daria Kalugina’s inventory overfloweth.

Trüberbrook opens in a small town in the middle of nowhere in 1967. The main character, Hans Tannhauser, is a physicist who wins a trip to a tiny German village called Trüberbrook. Once in town, his PhD thesis is stolen by a mysterious man. As Hans goes deeper in his investigation of this incident, he uncovers a greater task.

Things we collect, and events we find ourselves in pile up during the course of the game: stacked on top of each other, events turn from searching for the stolen paper to saving the world, from collecting random objects to building a quantum discriminator out of them. As it usually goes with the adventure games, the objects play the vital role of a narrative engine, yet in Trüberbrook this objecthood pierces the entire game with its physically-crafted miniature scenery.

The collection of things

Trüberbrook has 5 chapters and a prologue, six areas you can explore, about 15 locations you can end up in. As expected, each location contains things that you can, can’t, and can not yet interact with. The game is heavily infested by easter eggs and some cultural ready-mades – as the designers confessed to taking their inspiration from X-Files and Twin Peaks – to the point that these influences shape the fabric of the narrative.

You view Trüberbrook as a collection of small things. Sometimes it’s the usual stuff you find carefully placed along the thread of a point-and-click adventure: quotes and references for us to pick up; objects lying around for us to pick up and to carry through the game; other characters’ stories to listen to. But the scenery of Trüberbrook can be viewed as a collection as well: a collection of handcrafted pieces of decoration put together, which in turn slice the in-game world into particular scenes or locations, not only being limited by abstract reasoning, but also by the very physicality of its production.

Objects of narrative exchange

It gathers together the little gems of crystallized cultural artifacts that we love to recognize. It is flooded with Twin Peaks references from general tone to music and particular quotes, yet this doesn’t make the game repetitive or exhaust a familiar narrative. It doesn’t exploit a sense of nostalgia either. Rather it presents a transcending reference hunt, avoiding the dangers of being a mere rehash of existing cultural entities. It’s as if the whole game is split into two narratives: one is a pretty simple, sometimes grotesque story of a guy looking for his stolen paper, who eventually saves the world, and another this elusive sequence of familiar patterns, which doesn’t have any kind of resolution.

While hunting for references, we collect random objects in our inventory along the way. Items in adventure games have the quality of Chekhov’s gun – meaning that they appear for a reason, and they will “fire” at some point (although maybe not so dramatically), even if their intended purpose is often obscure. The hiking boots we get at some point are no use to us unless we trade them for a snuffbox, only to trade that for a boat trip voucher that finally gets us to a new location. Each thing has its place in a scene and its role in the act.

Both cultural ready-mades embedded in the narrative and the operable in-game things become the rods of the narrative engine. The former place you within a wider cultural landscape, the latter are responsible for the activation of time, as the story develops only when all necessary objects are collected and perfectly lined up.

Constellations

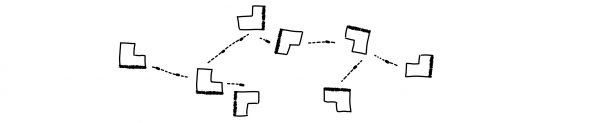

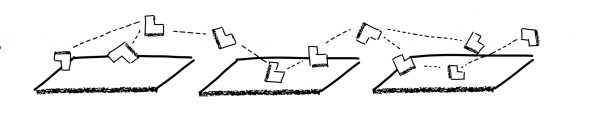

Since we have to find the specific object to use it in a specific way in particular circumstances in order to progress the story, the in-game objects turn into corpuscles of time. The constellations they shape, as we solve the puzzles, become the timeline.

Any constellation is a kind of narrative reach – drawing a figurative line between the dots to distort their appearance or purpose. This is also true within the narrative of Trüberbrook: in the manner of the mantra of Twin Peaks, things are not what they seem: a fox becomes a cat, and you travel on a hanger as a valid replacement for a cable-railway car. This brings a certain level of abstraction to the table, making specific objects into universal tools, reducing them to the name, or their role in the play. Hans meets Klaus the cat as soon as he arrives in the town of Trüberbrook, yet they don’t immediately engage. While we are taking care or more urgent things, the cat-fox appears here and there in several locations, teasing the possibility of interaction, before finally ending up in our inventory. But it doesn’t matter really whether Klaus is a cat or a fox, what matters is that you have to rescue him in order to proceed.

It seems our inventory can fit almost every weird object, every bit of timeline triggering the story. Hans notices that too and jokes about it a couple of times, then looks straight into the camera.

Places, non-places, and situations

The characters of the game sometimes step outside their world, whether by questioning the nature of their relationship with the player or simply looking straight into the camera, as if on stage and breaking character.

In the spatial dimension, the stage of Trüberbrook has several areas where the action can take place. These areas gradually open to us, and later in a game, we acquire the ability to fast travel between them, significantly increasing the level of abstraction yet again. These areas, places on a map, are divided into smaller locations: parts of town, stores, and rooms of buildings.

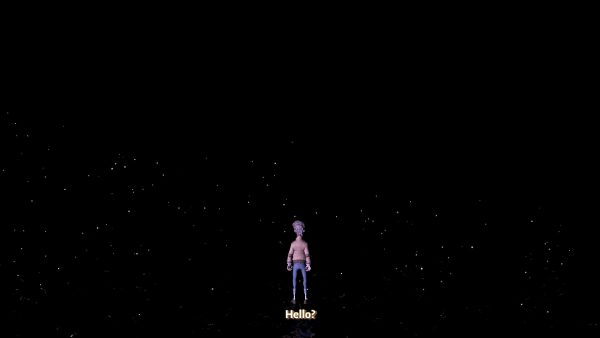

On the other side, the narrative is packed within several chapters, divided like a play into acts. And like small intermissions, there are non-places in between chapters, black space with little possible interaction filled with floating white dots like stars not yet connected into constellations, similar to the things you have engaged with or collected but not yet connected into the narrative. Chunks of the story presented by chapters, the space presented by those non-places, and fragments of time embodied by the charged objects from our inventory, constitute the essence of the game, and the spatial becomes situational. The action doesn’t develop strictly linearly, rather it unfolds in these stackable situations, which you have to resolve or address by shaping smaller narratives, either with stories people tell you or with things you gathered.

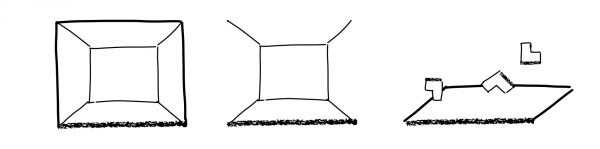

The biggest thing in the universe of Trüberbrook is the game world itself. The physically handcrafted setting questions the reality of the game – the setting is highly realistic yet visibly not real. Here comes another side of the joy of recognition: the double-edged realism of the model.

I love thinking of games as models that can introduce us to things outside of our day to day experience, but this time the artificiality of the game is taken literally, as the setting of Trüberbrook is a decoration made of noticeably handmade real objects carefully put together. The level of detail is impressive, as we look at the very real thing while being tricked by the diorama. So here goes another instance of this double nature of Trüberbrook, another weirdness of this objecthood, which also makes this game a series of confrontations: props are opposed to time, highly detailed decorations are set against the unreal nature of the model.

Throughout the narrative, collected things and the stories of other characters are molded into a bigger complex entity, spreading in every direction within and outside the world of Trüberbrook. In the meantime, the task at hand keeps getting amplified with every new step and iteration, to the point where the very weapon needed to save the day is made of random things molded together into the super-object capable of resolving the piled up urgency of the game. Trüberbrook is a collection, like a box full of little boxes, hiding inside things of double nature: obscured objects and the stories behind them, detailed scenery and abstract spaces, grotesque yet realistic.

Daria Kalugina lives in Moscow. Sometimes she works in artistic education, and dreams of building fictional worlds for learning.