2017: The Year of Triple A

Big Budget Blockbusters abound in today’s list, featuring Assassin’s Creed: Origins, Yakuza 0, Prey, Dishonored: Death of the Outsider and NieR: Automata.

Assassin’s Creed: Origins

To puncture the memory of the common Orientalist is an arduous task: the collective fabrications of Ancient Egypt have obfuscated much of the turmoil wrought under North-Western hegemony. Ptolemaic Egypt presents a unique opportunity for Assassin’s Creed: Origins to breathe life into our imagery of the Nile delta and its surrounding territories, under imperial assault by Greeks, Romans and their collaborators. People with ordinary problems form the spine that can support a representation of colonialism – simple as this one is.

Greco-Roman architecture suffocates the urban center of Alexandria: one marble statue after another. For once, it does not feel like stepping on these buildings triggers a disconnect, an affront to the people who suffer the ground below. Instead, it is a way to utilize the invaders’ boundless vanity against them. The vengeance of Bayek, initially one of video games’ countless fathers who have lost their child, is cathartic because it is directed at a clear and timely foe: conspiracy, corruption and invasion. It is more than vengeance, too, eventually: care.

The spectacle of a golden-tipped pyramid shot through with the splendor of the sun is juxtaposed with the joys and plights of a living, breathing population that inhabits and performs sophisticated technologies as well as deeply personal burial rites in lands we have made plastic and unapproachable. At least partially, there is comprehension in this portrayal: the desert is blooming one oasis after another, seas of grass and flowers, temples bustling with festivities and ritual.

Origins, of course, cannot stem the tide and often falters on the weight of its own statements: the desire to breathe life into history and to reduce history itself into a deterministic narrative between two warring factions steeped in conspiracy is not absent here. But through the cracks shines some color, at last.

Yakuza 0

Yakuza 0, and by extension the entire Yakuza series, show us how people evolve over the course of time. How many games do you know that have their protagonist completely change occupations, from criminal to real estate broker no less? Out of any video game series I can think of, it comes the closest to charting an entire life, with Yakuza 0 acting as the gateway drug to the person of Kazuma Kiryu. In its main story and even the smallest sidequest, Yakuza 0 stays true to one central message: lives change, but as long as you stay true to your ideals, it’s all going to work out somehow.

Both Kiryu and Majima come in conflict with their ideals. Kiryu finds himself betrayed by the people he trusted and has to re-evaluate his relationship with the yakuza, while Majima, who values his life as yakuza, still finds himself interfering when an innocent faces harm. When it lines up with their ideals, Kiryu and Majima help without prejudice.

Yakuza 0 also makes it a point to constantly defy our assumptions about people – yakuza, for all their crimes, are still bound by honor. Kiryu isn’t even half as scary as his frowny demeanour and intimidating walk suggest, just as the people he meets are also never what they seem to be at first glance. Between a counterfeiting artist with a heart of gold and a dominatrix who needs help in giving her customers the best experience possible, this game is all about the crazy things people do to get by.

In all its drama, Yakuza 0 manages to be honest about the ups and downs of each life and provides us with some optimism in the form of two men who are working hard both for their success and that of others.

Malindy Hetfeld is a freelance writer you can find in places like PC Gamer and Polygon. As a Japanologist, she is interested in all things Japan and can be found reading three books at once at any given time. Follow her on Twitter for a chat.

Prey

A theoretically “open-world,” first-person explore-them-up, Prey strikes a stunning balance between its wide-ranging gameplay and its closer, more intimate heart.

Talos I is the star of the game. It’s a cohesive space station, lovingly done up as a Metroid-style obstacle course, but with all the granularity of Gone Home. Prey is the sort of piece where the environment is as important as what populates it, where every object and item is placed with intent that need not be parsed, but allows for it.

Speaking of Prey’s loose objects, the game’s first half strikes a serious paranoiac note via the Typhon mimics, aliens who will copy objects in their immediate vicinity. What this does in practice is to enforce suspicion of any collection of two or more identical things. Two chairs knocked over? Better hit both of them with a wrench, just in case. Was that coffee cup there before? Well, yes, but now it’s flying across the room (that’ll teach it). As the Typhon infestation becomes immanent, this tension sadly fades, but when it does, it’s replaced by the sheer joy of pitching pressurized gas canisters at their faces.

“Thoughtful” might be a stretch, but sometimes what you need is a big pile of well-intentioned pulp. Prey’s mechanics are gleeful, while its ideas are writ large, and it never lacks for humanity – the most ironic twist of all.

M. Alasdair MacKenzie is a local media critic of small consequence whose work can be found at Sharkberg and on Twitter.

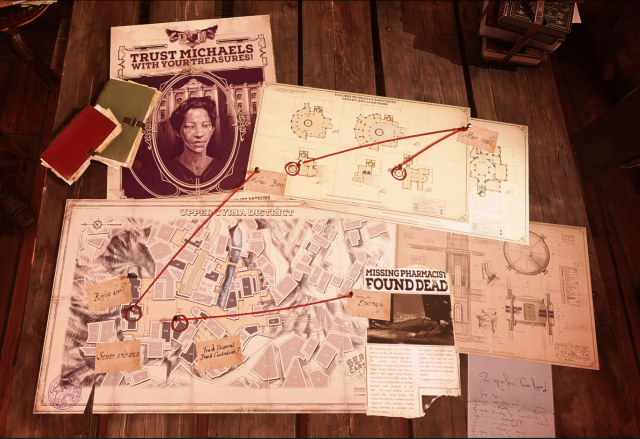

Dishonored: Death of the Outsider

The stand-alone Death of the Outsider complements Dishonored not with the series’ customarily hapless attempt at an already compromised moral high ground, but with the unabashed pursuit of vengeance. Its brand of justice is a more intimate affair sans complex chaos/morality systems; the choice over whether to spill blood or not is left to the player. No judgement, except our own.

At last, there is a protagonist not drawn from imperial provenance: Billie Lurk is the remedy for a tonally recalcitrant series that has attempted to bring catharsis to players by letting them inhabit an “enlightened” monarch and her agent.

Another entry into the series and a year later, Lurk is on the prowl and though her primary target skews towards the series’ supernatural dispositions – the Lucifer-esque figure of the Outsider – the way to get there is pragmatic: there is a cult that needs to be identified and then infiltrated, with the inner circle posing as the initial targets for Lurk’s assassinations. Most notably, the trail of breadcrumbs leads through a phenomenal bank heist past an elaborate security system including electrified floors, complicated passcodes and a constantly moving vault, towards the resolution of a central mystery: who is the Outsider? And, more importantly: is he to blame for the events that instigated the series and proved lethal for so many innocent people, for the turmoil in Lurk’s life?

In an exercise of blatant voyeurism, Dishonored rips architecture apart to reveal a clockwork people: players are given powers that let them become a horror upon unsuspecting enemies, or simply a specter dancing through the gaps in the gears. To me, it is a simple, playful puzzle: how to traverse the level without being seen, but while taking in as much of the world as possible; it is a lesson on how to become a shadow, deadly or not, but always listening.

NieR: Automata

Out of every “game that could only work as a videogame,” none deserves the title more than NieR: Automata. A large part of the journey involves hacking other entities, experiencing combat fatigue, and narrative choice. It’s pretty difficult to use any of those mechanics in a film or book. But NieR utilizes each one masterfully, and takes full advantage of gaming’s most powerful tool: immersion.

By immersing the player in the roles of 2B and 9S, NieR provides a fascinating case study for the concept of perception. How can information, or a lack thereof, shape a story, mindset, or identity? How can a shift in camera angle so masterfully transform a scene? How can two people see a situation in vastly different ways? These answers are hard to articulate, but NieR conveys them through player immersion. There is no need to imagine walking a mile in another’s shoes. NieR does the imagining on its own. All that’s left is to simply care for the characters, invest in the story, and experience the changing viewpoints.

NieR: Automata is a story about robots and androids, yet it contorts the limitations of game design to provide deep commentary on human interaction. It doesn’t just preach sermons on empathy or spout analogies; it lets the player revel in them. It truly can only work as a videogame.

Dylan Bishop is a freelance writer, seen previously at Outpost and Zam. He loves diving into video game mechanics, but more importantly, he loves relaxing anime. Catch him discussing Zelda, Persona, and Cowboy Bebop on Twitter.