Opened World: Kentucky Route Zero Act I

Miguel Penabella encounters the ghosts that haunt the South.

This is part one of a comprehensive overview of Kentucky Route Zero. See also: Part two, part three, part four, and part five.

What do ghost stories mean? The ghost story reflects a temporal rupture, in which a dead soul from the past anachronistically lingers on in present-day spaces. Ghosts haunt specific locales or objects, unable to rest because some unresolved trauma must first be settled. In this sense, ghost stories are not so much scary as they are sorrowful and tragic. These wayward spirits have been wronged in their past life, and their inauspicious presence is simply a call to remember that something must be fixed.

In Act IV of the sprawling Kentucky Route Zero, a signpost perched next to the subterranean Echo River commemorates the death of twenty-eight miners sacrificed to corporate greed. “When the walls collapsed and the tunnels filled with water” is the moment the sign recollects and mourns, framing the narrative of the game with human loss. These miners haunt the main story of Conway’s delivery to 5 Dogwood Drive through the secretive, unmapped, dream world of the Zero, an underground highway somewhere off the grid. The miners are some of the many ghosts that linger on in the spaces of Kentucky Route Zero. The setting of the game reflects a surreal reimagining of Kentucky, in which histories and local myths overlap. Characters remark upon a great flood that claimed human lives and altered the very topography of Kentucky, washing away land and destroying homes and livelihoods. The overarching evil of the monopolistic Consolidated Power Company further ripped families apart during this moment of crisis. Buildings have been repurposed in the subsequent economic downturn, resulting in a palimpsestuous layering of mismatched histories. There’s even a department that conducts this work, Act II’s Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces, which approves the conversion of a derelict hospital to an auto dealership or a cavernous cathedral to an office building. Later still, characters will enter a ruined church that houses a sparkling underground reception area to the expansive Hard Times whiskey distillery and subterranean river. In these places, the past is visibly marked on the present. A cathedral may now house drab office cubicles, but turn a corner, and a towering organ leftover from the church emits a mournful dirge, hallowing the memory of a place not quite there anymore.

Kentucky Route Zero is also a game haunted by financial ruin, recession, and displacement. In an interview by Lewis Gordon with the Cardboard Computer trio Jake Elliott, Tamas Kemenczy, and Ben Babbitt, they assert that the game is specifically addressing both the “2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession,” as well as “post-industrial capitalism,” pointing to narrative markers like foreclosure, repossession, predatory lending practices, and insurmountable medical bills and student loans. Throughout the game, Conway and his dog will meet an array of laid-off, debt-ridden, and itinerant drifters. In the first scene of the game, Conway befriends Joseph Wheatree, a wizened artist who holds an advanced degree in electronic writing (twelve years of schooling, he remarks) but now lounges idly at the beautiful—if disused—Equus Oils gas station. Along his journeys, Conway also bumps into the elusive Weaver Márquez, a mathematician who fled her past life due to mounting debts, leaving behind her cousin Shannon.

People like Weaver may slip between worlds, and places may be repurposed by the Bureau of Reclaimed Spaces, but debt will always remain. Debt is one ghost in Kentucky Route Zero; it haunts the abandoned Márquez farmhouse, banishing human life. Upon arrival at the farmhouse, Conway finds it half-shrouded in eerie fog and twilit darkness, sitting next to a graveyard. With belongings boxed up and a lack of activity within the house—save the brief return and ghostly vanishing of Weaver—the scene envisions a family that has been broken up by financial downturn. What debt does is prevent impoverished peoples from planning for the future. The future narrows and is ultimately foreclosed to the duration of one’s debts. Sam Dibella examines the rezoning of space as contributing to a hazy, indistinct history, and this sense of uncertainty defines the game. Characters like Conway lose grip of their memories, un-anchoring them from the past. Not only do these gaps make the narrative all the more vaporous, it also renders characters more susceptible to the behavior of the Consolidated Power Company, which preys upon the desperate and vulnerable.

Almost all the characters Conway runs into are in some way beholden to debt, particularly to the Consolidated Power Company, whose game is exactly that: consolidated power. The Company is to blame for the aforesaid disaster at Elkhorn Mine. In a reckless effort to cut costs and maximize profits, the Company required miners to purchase their own safety equipment rather than supplying it themselves, implementing a truck system arrangement in which workers paid in plastic tokens could redeem canaries and respirators from the Company store. Consolidated Power also rationed the electric system to save money, leaving workers scrambling to micromanage the lights, water pumps, and PA system, all of which threatened to shut down given the lack of adequate power. Miners had to pay to operate the fans that would filter in clean air, suggesting that working in the mines was a form of risk management. When the tunnels flooded, the rationed power was not enough to operate the water pumps that would save them, and the miners—including members of the Márquez family—drowned in darkness.

The game situates the recent financial crisis within a broader history of American exploitation in the South. The Consolidated Power Company’s lethal mismanagement of the Elkhorn Mine recalls tragedies like the 1970 Hurricane Creek mine disaster, in which countless safety infractions were ignored and mine operators “valued profits far more than they did the safety of their miners.” We have seen more such tragedies in recent years. Following the 2010 Upper Big Branch Mine disaster that left thirty-eight dead, mining company Massey Energy threatened to fire workers who attended funerals of their killed brethren instead of returning to work. As one miner observed, “They don’t give you boots or a helmet; you have to buy it yourself,” and the company forces miners to work “to the bone.” A traumatic history of the region’s coal industry thus provides the real contexts for Kentucky Route Zero’s fictionalization. Beyond Kentucky, even earlier generational violences of post-industrial capitalism inform the game, as it lifts imagery directly from the Great Depression. Superlevel’s crucial rundown of the artistic and historical influences of Kentucky Route Zero identifies direct references to Farm Security Administration photographer Russell Lee, whose photographs of coal miners in Kentucky’s Harlan County serve as the visual foundation for the game’s Elkhorn Mine. By pointing out such references, the article suggests the game’s place in a much larger historical reckoning with economic crisis and American poverty that is often hidden from view. Players need not slip into the subterranean dream world of the Zero to find these stories; these places already exist in reality, enveloped in grief and falling apart.

As Conway journeys to the fabled Dogwood Drive, the game also allows players to leave the main interstate to discover short vignettes of everyday life, painting a more complete vision of a dreamlike, rural Kentucky. Traumatic pasts like Elkhorn Mine may haunt the game, but the fading, nostalgic memory of a small-town South lingers as well. Conway can visit various half-forgotten sites, including a ramshackle diner, its occupants obscured in darkness; a strange, abandoned museum by the side of the highway; and an empty church where ghostly hymns radiate through the walls. These all represent markers of fading small towns plagued by economic downturn as factory and mining jobs increasingly migrate to an outsourced labor pool abroad, leaving these communities depopulated and impoverished. After the player exits these vignettes, they disappear from the map and can no longer be accessed, as though they’ve vanished from reality like a vague dream. Patrick Larose examines the game’s random encounters in an astute essay, arguing that its road trip narrative confronts “the real histories of the country, the people in it, and the people being hurt.” Sites like a once functioning museum suggest that these towns were once prosperous, but in a post-industrial Rust Belt landscape, such communities are in a perpetual state of decay.

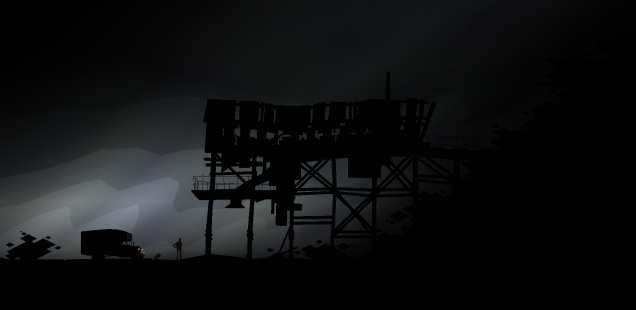

While the world economy accelerates and adapts to the 24/7 demands of global capitalism, these small rural towns remain inflexible, clinging to the desperate, state-sponsored myth of coal jobs returning even as employment opportunities evaporate with automation, outsourcing, and renewable energy sources. The permanent residents of Kentucky Route Zero are few, but Elkhorn Mine stubbornly stays rooted in place, greeting Conway with an ominous fog and darkness that lends the scene a supernatural quality. Shannon is introduced here; her first exchange with Conway involves either the fear of being displaced or the existence of ghosts, both of which encapsulate the central themes of the game. When Shannon asks if he believes in ghosts, Conway poetically replies, “I do believe a place can be haunted,” further adding that people can be haunted too. As Shannon and Conway venture deeper into collapsed mining tunnels via a rickety old minecart, they plunge into a space untouched by the movement of time aboveground. Equipment lies abandoned, and flyers and drawings remain tacked up since the accident. Elkhorn no longer functions as a mine but rather as a crypt, a mausoleum of time trapped in amber (or trapped in water, in this case). Indeed, by switching off the light while riding in the minecart, the flickering sparks overhead illuminate the literal ghosts that haunt the mine. Kentucky Route Zero is not a violent game, but there is violence present here: institutional violence, corporate violence. Borrowing from Larose, spaces like Elkhorn Mine are “covered in scars,” symbolizing the great sin that haunts the game. Over the course of the acts, anger over the preventable death of twenty-eight miners gives way to profound sadness, revealing the tragedy at the core of Kentucky Route Zero’s ghost story.

And yet, despite this economic and social rot, amidst the abandoned mine tunnels and lonesome night streets, a sense of adventure endures. Conway finds companions, forms relationships, and travels with friends united in their shared financial woes. This is the hopeful solution that Kentucky Route Zero deploys against hardship. Simply desiring to know more about a stranger is worthwhile, imploring the player to travel and learn. Seemingly unimportant exchanges leave a lasting impact years down the road; the game reflects the desire for human connection in uncertain times, asking us to empathize with people living amidst fiscal breakdown. If ghosts have been wronged in some past life, kindness serves as the corrective. Once aimless and isolated, the chance encounter of characters imparts newfound clarity and purpose, perhaps guiding them towards a way out of ruin, together.

In future installments of this comprehensive overview of Kentucky Route Zero, I’ll be moving from Elkhorn Mine and the game’s themes of debt and financial ruin to an examination of the game’s magical realist South and dreamlike sense of time and travel.

Miguel Penabella is a freelancer and comparative literature academic who worships at the temple of cinema but occasionally bears libations to videogames. His written offerings can be found on PopMatters, First Person Scholar, and Unwinnable, and he blogs on Invalid Memory.