The Miracle Animal and the Pale Inside: Existential Thought in Disco Elysium

Keith Gordon, first and foremost, is.

This essay contains spoilers for Disco Elysium.

The first thing we learn about Harry Du Bois, the detective protagonist of ZA/UM’s Disco Elysium, is why he drank himself into a state of total amnesia. The femme fatale finishing her cigarette on the mezzanine outside their hotel rooms says she heard some of the drug-fueled “destructothon” from the night before. She tells him that she caught some of what he was screaming before passing out in a blaze of self-annihilation. “I think you screamed that you… didn’t want to be ‘this type of animal’ any more. I may have misheard, but it was sort of memorable.”

What kind of animal is Harry Du Bois?

I.

Disco Elysium opens in blackness. Awakening, you find yourself in a dilapidated hotel room, in a dilapidated district, in a city full of past glories and occupied masses. Yet the player can quickly orient themselves because the game is set in a world its creators describe as “a modern fantasy world, a fantasy world in its modernity, which roughly corresponds to the middle part of our XXth century.” This allows the authors of the game to explore modernism: a set of interlocking cultural, philosophical, and aesthetic movements born out of the ashes of an obsolescent feudal order. ZA/UM is interested in these movements because they offer “a world with a promise of non-staticness, meaning, things appear undecided— they could go one way or the other.” In many ways this is the sole defining feature of modernist movements: the belief that things must change, that a new and better way of being can be found. One of the modern philosophies that most informs Disco Elysium is existentialism, the product of a loose group of thinkers who were concerned with freedom, authenticity, consciousness, and nothingness. While the similarities between the game’s setting and our own world help ZA/UM explore these ideas more explicitly, the chief vector for the metaphors they use to discuss existentialism is also the game’s largest intrusion of the fantastic— the pale.

Enough of the setting of Disco Elysium corresponds to real history for players to catch on quickly. We learn that a communist revolution started in a country called “Graad” and quickly fill in “Russia.” The pale defies this realism. It is easy to miss, and it is possible to finish the entire game without once learning about it, because characters are loath to talk about it. If you do manage to plead your way into a discussion, you are first left with the impression that the pale is like the open seas: an obstacle between continents that, once conquered by technology, allowed the setting’s Europe analog to dominate the world. But the pale is weirder than that. Asked to describe it, the erudite executive Joyce balks. “The pale is the enemy of matter and life. It is not *like* any other— or *any* thing in the world. It is the transition state of being into nothingness… That’s right— the negation of being. It’s difficult to describe— or even measure— something whose fundamental property is the suspension of properties: physical, epistemological, linguistic…”

And it is spreading.

The pale’s explicit role in the game is small. It informs a few characters’ backstories, it plays prominently in one major side-quest, it serves to disorient the player and strengthen identification with the protagonist as the two learn simultaneously of this disquieting anti-entity. Beyond this, however, the choice to make nothingness an (anti)physical aspect of the setting allows the creators of Disco Elysium to highlight the problem of being and foreground the existential themes that inform so much of hardboiled fiction.

II.

Jean-Paul Sartre, the only major existential thinker to apply the label to himself, broke down human consciousness (or “being”) into two facets. “Freedom” is the subjective, first-person facet. It represents autonomy, choice, control. “Facticity” is the objective, third-person facet. It represents all sorts of constraints on our actions: social, physical, historical. This divide can be seen in the split, inherent in any role-playing game, between you as the player and Harry as a character. Just as discussing any RPG requires moving between a first-person understanding (“I decided to work with Evrart”) and a third-person understanding (“Harry’s karaoke scene was hilarious”) discussing human consciousness also requires the ability to move between these two facets.

Sartre posited acting in bad faith to be the result of someone ignoring one of these facets. In his view a man who continues to work at a job he hates is acting in bad faith, as is a woman desperate to have been born in a different time. The man is ignoring his freedom, he does not recognize he has the ability to find a different occupation. The woman is ignoring her facticity, she does not recognize that no act of will can allow her to rewrite the circumstances of her birth. Either of these acts of bad faith can be painful. Sartre describes existential angst as being overburdened by freedom. He describes standing at the edge of a cliff and fearing not that you might fall off but that you can choose to jump. One can also be overburdened by facticity: refusing to choose, often between terrible options, or living excessively in the past. Over and over in Disco Elysium we see characters stuck in the past, refusing to use their freedom to remake themselves.

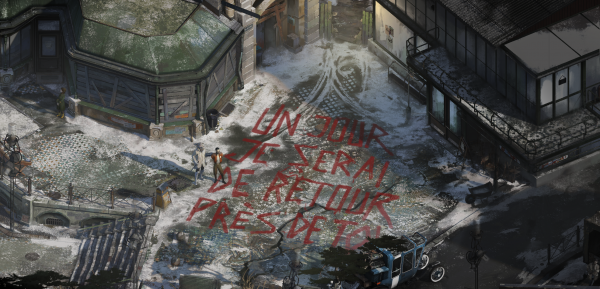

Harry du Bois is still haunted by the end of a romantic relationship six years past. Martinaise, the forgotten neighborhood in which the game takes place, is still shattered from a war that ended fifty years ago. This kind of curdled nostalgia, turned (anti)physical, is often used in-game to describe the pale itself. Harry is told that dialectical materialists “argue that pale somehow *consists* of past information that’s degrading. That it’s rarefied past.”

A dockworker’s strike has shut down traffic in Martinaise, turning the streets into a temporary village of trucks and drivers. This is where Harry meets the character most affected by the pale’s manifestation as an overdose of facticity. The only name she gives is “Paledriver.” She is a long-haul trucker who transports goods through the pale, and the prolonged exposure to unbeing has unmoored her from reality. Paledriver hates the world and longs for it to be consumed by nothingness. She refers to the pale in the plural: “’…they will win. They’re *coming* for this, you know…’ She looks around. ‘All of this.’ She seems to derive some bitter pleasure from this strange thought.” It is difficult to follow Harry’s conversations with Paledriver. She prefers living in the memories of others, which she has been exposed to during her time in the pale, to dealing with her actual life. Paledriver hates being reminded of the present: “…everything is made out of plastic. Why do you need plastic? When you can make the world out of amber?” She would rather trap the world in stasis, and live in the sepia-toned glow of memory, than see things how they actually are.

Paledriver is filled with “terrible nostalgia. For yourself. For humans. It’s too much to bear.” Her nostalgia borders on nihilism, showing the game’s agreement with Sartre that both facticity and freedom are necessary aspects of consciousness. Paledriver has the freedom to live a life more in-line with the archaic values she has been exposed to but instead chooses to wallow in her nostalgia. She speaks of abandoning reality longingly, unable to tolerate being. “What are we *doing* here? For thousands of years… it doesn’t have to be like this. We can just give up. We can just become vapor.” If the player asks her about the legend of the Motorway South, a part of the pale where “…the process begins. Erasure. Kilometer by kilometer. In any direction,” she ultimately loses herself in rapture, unable to speak aside from sighing “Hosianna,” her use of liturgical language indicating a twisted form of salvation. Harry’s internal thoughts on the Motorway South makes the appeal of the death drive manifested by nostalgia clear: “to reach the end of the Motorway South is to be *unborn*. You’ve had this thought before… A lost piece of the man you were. A dark hope.” This dark hope though is no true hope, as the pale isn’t actually “rarefied past” but instead, as unthinkable nothingness, can merely be analogized by calcified time. The salvation Paledriver craves is pure annihilation, and while there may be ecstasy in annihilation there is certainly no hope.

The pale-as-the-past is the first way in which the pale stands in for nothingness. It lines up neatly with Sartre’s view of a fixation on facticity, and serves as a challenge to the creators’ stated goals of evoking the “non-staticness” of modernity. By focusing only on the way things were we can end up blind to the way things could be.

III.

While Sartre broke being into two facets, freedom and facticity, he wrote of an equally important flipside to consciousness: nothingness. Uniquely, humans are aware of unawareness. After Joyce first tells Harry of the pale, Inland Empire, the skill representing his insight and intuition, may chime in: “Suddenly you’re conscious of yourself standing there, on… whatever this all is. Your arms hang down by your sides.” Every invocation of nothingness implicitly reminds us of somethingness, of our own existence. Existential nothingness is the final and truest metaphor the game employs the pale to explore.

Twice throughout the game, first in a conversation with Paledriver, Harry comments that he felt the pale inside of him. He tells her “I feel I already have what you have. In some way.” His interest in “amateur-entroponetics” and his sensitivity to the human condition have shown Harry that being inevitably gives rise to nothingness. The same perceptivity that makes Harry Du Bois both an incredibly effective detective and an incredibly unstable human also allows him an intuitive awareness of the nonexistence that lurks on the other side of the world.

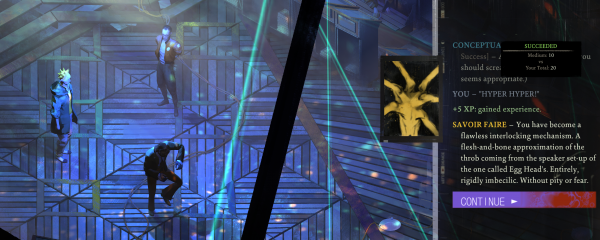

This is made clear towards the end of the game during a conversation with the Insulidian Phasmid. The Phasmid is a rare insect with strange properties but is otherwise natural. Harry’s conversation with it is gated behind an Inland Empire skill check, which makes it clear that the conversation is an intuitive understanding made cognizable by Harry’s imagination.

The Phasmid at first simply says “I exist.” This references Sartre’s famous proposition that “existence precedes essence,” an argument which claims that first and foremost things exist and only secondarily do we make meanings for them. Harry responds that he too exists, and the Phasmid asks him to characterize his being. Harry may say being for him is like “Fire, burning… On the horizon. Pale fire. This thing we’re both sensing is coming to an end.” The Phasmid responds “That is your problem. Nothing ever ends for me. There is only room for two, maybe three pictures in my mind.” Harry may characterize his being as ill “In my heart. For me it’s sadness— input after input.” His sadness is rooted in his nostalgia and so here he uses the pale-as-the-past metaphor. The Phasmid responds “For me it is not like that. I have states, not emotions. For example, I experience excitement at unexpected sugar rewards, but that is not important.”

These two exchanges underline a major point about nothingness: that understanding it is unique to humans. We are told that being requires an awareness of the possibility of non-being and that, distinctly for human animals, being *hurts.* This is confirmed by a seemingly paradoxical line spoken by Joyce much earlier in the game: “Even animals aren’t animals… Living organisms don’t identify with abstractions. Elysium is for particular beings.” The Phasmid agrees: “All of nature is kind of horror, or strife— though none of it as horrible as you.” It confirms that we are unique in containing the knowledge of nothingness, saying humans are “extreme, all-engulfing madness. A volatile simian nervous system, ominously new to the planet. The pale, too, came with you.” This is why Harry, annihilating himself the night before the game begins, wished to be a “different kind of animal.” He couldn’t bear carrying the pale in his being.

The Phasmid describes human beings as “…a violent and irrepressible miracle. The vacuum of cosmos and the stars burning in it are afraid of you. Given enough time you would wipe us all out and replace us with nothing— just by accident.” Here the game underscores the distinction between nothingness as we understand it— a shadow or antipode of being— and nothingness in the scientific sense. This is why the “vacuum of cosmos” is afraid of us. Before self-aware organisms existed there was simply void, intruded on by stray bits of matter and rays of energy. Once humans began to contemplate the vacuum, however, it transformed from emptiness into nothingness, into the pale. We replace even emptiness with nothingness simply as a byproduct of knowing there is somethingness. The vacuum should be afraid of us.

This is a bleak moral, and one existential thinkers did not shy away from. They counsel us to face the fact that no consciousness orders the electrons spinning across the vacuum, and to know that knowing this removes you from a potentially pure state of existing as a living organism. You are doomed to being. However, existentialism does not rest here. Just as the game quietly condemns Paledriver’s nostalgic nihilism and Harry’s destructive longing for his ex-lover, it also offers a way forward that Sartre would approve of.

IV.

Existentialism holds that nothingness is an inevitable byproduct of being, and knowing this makes humans aware of the arbitrary nature of the universe. It deems that nature “absurd,” and warns us not to flinch from this understanding. To pretend the world isn’t painful, arbitrary, and terribly absurd is to deny oneself an honest chance at moving through and beyond that terror. When discussing the pale, Joyce makes a similar point. She describes the pale as “very *disco.* You’d love it.” Harry responds “Doesn’t sound like any kind of disco I’d like to go to.” Joyce: “’But you already have,’ she looks around. ‘And you’re doing just fine, despite the rubble.’” The Phasmid uses similar language when it tries to convince Harry to move past his ex-girlfriend. “I also have one more thing to say to you: that woman— turn from the ruin. Turn and go forward.” The existential viewpoint sees the world as a ruin, failed by so many systems of meaning that humans have tried to believe in— very much like the neighborhood of Martinaise where Disco Elysium takes place.

Existentialism however offers more than stoicism in the face of a cold and absurd universe. It offers hope: particular hopes, made by each individual. Accepting that nothing has an essential meaning offers people the freedom to make their own meanings. This is illustrated in the game after Harry helps a computer programmer named Soona investigate a two millimeter hole in reality, “the swallow,” in an abandoned church. Also helping with the experiments is a group of kids who wish to turn the church into a dance club. Soona eventually comes to endorse their plan, and comments “…maybe a club for anodic music isn’t the *worst* thing you can erect around this… particular *point in space*?” Harry affirms her instincts: “The club is the only thing keeping this place— and the rest of reality— together.” This is true not because music or emotion has any special effect on reducing the spread of the pale, but because a dance club is a space where people come, knowing the absurd indifference of the cosmos, and choose to *dance.* There is no essential human nature, and so we may choose to create our own natures, to throw ourselves into whatever projects we find important. Making music, creating social spaces, programming games, establishing perfect communism— all of these are possible meanings, all of these are anti-pales.

The fact that the swallow is located in a church follows this pattern. Soona says “It didn’t form in a church, the church formed around it… [by settlers] acting on an instinctual level.” Religion too is an absurd choice that can nonetheless give a life meaning if it is chosen freely— it was the choice that Kierkegaard, arguably the first existentialist, made for himself. That any potential meaning is subjective is underlined by a quick disagreement at the end of a dance sequence in the club newly established in the church. Noid, one of the kids trying to build the dance club, claims establishing the club is the “End of human development. Mission. Complete.” Harry has the option to be uncharacteristically dismissive: “I wouldn’t go *that* far.” Noid though has an unanswerable rejoinder: “I *WOULD*.” Harry cannot create meaning for Noid, only Noid can do that.

Living with the knowledge that being creates nothingness and that the universe is absurd and indifferent can be terrible. Our salvation isn’t the annihilation longed for by Paledriver or the enviable lack of self-awareness enjoyed by the Phasmid, but instead lies in creating meanings for ourselves. Building the dance club—whatever your dance club may be—is the only way to fight off the pale.

V.

The meaning that Harry creates for himself is being a detective. He is undoubtedly one of the greatest police officers in one of the toughest districts in one of the most important cities in the world. The depths of his feelings can result in a cavalcade of small kindnesses, in lives saved and improved and given the safety needed for a chance to make meaning. The moment you win the game is not saving as many people as possible during the climactic shootout, or arresting the murderer who is responsible for the game’s initial killing, or being allowed to rejoin your precinct. It is acknowledging Harry’s truth in conversation with the Phasmid.

“I’m glad to be me— an incredibly sensitive instrument.”

“Few of us can begin to imagine the horror of you— with all of creation reflected in your forebrain. It must be the highest of hells, a kaleidoscope of fire and whirling glass. Eternal damnation. Even when you’re sleeping… and when you wake, you carry it around on your neck… I feel great, mute empathy for you.”

“It was very disorienting at first, but I’m keeping my shit together.”

“That must be incredibly hard. The arthropods are in silent and meaningless awe of you. Know that we are watching— when you’re tired, when the vision spins out of control. The insects will be looking on. Rooting for you. And when you fall we will come to raise you up, bud from you, banner-like, blossom from you and carry you apart in a sky funeral. In honour of your passing.”

Harry’s Volition skill chimes in. “In honour of your will, lieutenant… That you keep from falling apart, in the face of sheer terror. Day after day. Second by second.”

That is the vision of hope offered by existentialism. To know that the world is indifferent, that nothingness lurks within and around you, and yet not to flinch. To know there is no essential truth— only choices you can make, most of them painful, most of them wrong. And yet, despite that knowledge, to wake up to the world and make those choices anyway. Day after day. Second by second.

Keith Gordon is a writer, public health researcher, and healthcare advocate based out of New York City. You can reach him at KeithJGordon at gmail dot com or on Twitter. He doesn’t tweet much, so don’t be surprised if his timeline is as empty as the nothingness inside of you.