Silent Stories: The Last of Us Part II’s Unusually Riveting Collectible Notes

Jenyth Evans loses herself in an epistle.

Before playing The Last of Us: Part II, when I thought of notes in video games, my mind would go straight to titles like Dragon Age or The Elder Scrolls. In their quintessential form, they are often used to expand game-worlds beyond the main story, mainlining lore or secondary characters’ stories straight to the player. While there’s nothing wrong with this – and, indeed, many people love notes in this format – they often add superfluous cruft to the game’s story, rather than meaningfully enrich it. They can pull the player out of actually exploring the world and, at their worst, become a barrier to the main story, a cheap way to pad out the gameplay length or to tell a player how to solve a puzzle. Judging the caliber of notes in games, therefore, often boils down to how they function as stand-alone pieces of writing, or how they form the misty lore-world of a game’s backstory, rather than how they interact with the main narrative. A set of notes in the Hillcrest chapter of TLOU Part II, however, showed me how they can go much further, recalibrating my experience of a level and even giving me greater insight into Ellie’s inner world.

By this point in the game, I was beginning to feel conflicted about Ellie’s growing obsession with revenge. Ellie and Dina had just barely survived the previous day, when they first encountered the Washington Liberation Front, the local dominant militia in the city, and an Infected horde. What’s more, Dina had just revealed she was pregnant, leaving both Ellie and I reeling and wondering what this meant for her campaign of vengeance. Personally, I just couldn’t see why Ellie was still hell-bent on going after Joel’s killers. I was much more invested in keeping Dina safe, and the isolation I felt starting this level without her only reinforced that. That being said, I had also just experienced my first substantial flashback to Ellie’s birthday with Joel at the museum. The familiarity of the mechanics re-deployed from the first game in this sequence, where Joel boosts Ellie through windows to access new areas, and the witty back-and-forth between the two brought together everything I loved about their relationship from the first game. I was torn, asking myself what I would do in Ellie’s position of loss—achieve some sense of justice, or draw a line under something so painful for the sake of others around me.

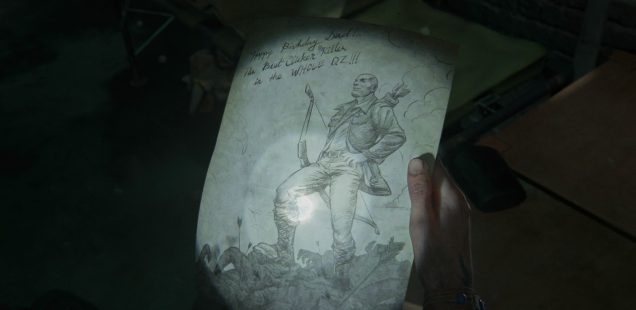

Amid these mixed feelings, I let Ellie lead me through this suburban neighborhood of Seattle. Early on, I picked up a drawing of a man, who I’d figure out from an archery trophy stashed in the corner, was called Boris Legasov. He was drawn in a heroic pose, brandishing his bow, with a caption praising his tally of dead Clickers. My mind instantly went to Joel: not least because, back at his house in Jackson, he had framed a portrait of himself Ellie had drawn. Perhaps Ellie makes this same connection, since she comments “That’s not bad,” as she picks the sketch up. But the style of Boris’ picture seemed like a metacommentary on Joel’s role in the first game. He was the “hero,” the protagonist with whom many people bonded. The discourse surrounding Part I and II confirmed that a significant (or, at least, very vocal) number of players saw Joel in this light. Here in Hillcrest, there was someone who felt similarly inspired by a protective father figure.

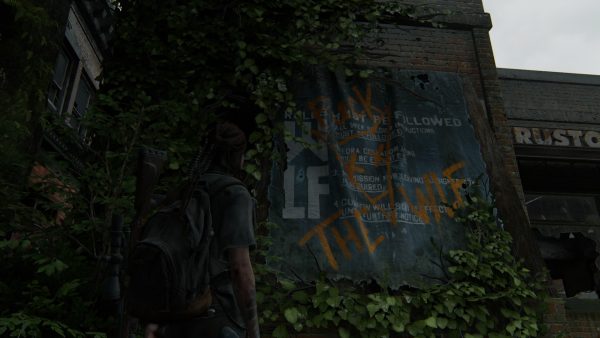

Another note reveals that the artist, Sofia, was Boris’ daughter, and she was killed after spray-painting over WLF regulations imposed upon the local area. Her handiwork is still visible on the tattered remains of the rules banner, offering a prompt for Ellie to copy it into her journal. Sofia was shot down by soldiers, just like Joel’s daughter Sarah at the beginning of Part I, but her rebellious streak and Ellie’s appreciation for it solidifies their connection further. More than this, it struck me that the same thing had happened to me many times in the first game. Sofia could have easily been Ellie, if she had died during any of the encounters she and Joel had with hunters, Fireflies, or FEDRA. All those deaths I had gone through while playing as Ellie represented what actually happened here in Hillcrest.

Further notes reveal the fallout from Boris’ insatiable grief. He kills an entire WLF patrol as vengeance, in a microcosm of Joel’s journey from father to cold-blooded survivor. Intriguingly, we find this out not from Boris, but from others living alongside him in the neighborhood. One author recognizes Boris was in an unimaginable position, conceding that, “Jesus… I get it, they killed his daughter.” Despite this, they still can’t condone his actions which put the whole neighborhood (never mind the whole world) in danger, concluding that “…he just signed our death warrant.” In these few sentences, I was already thinking again of the debates which flared over whether Joel was right or not to kill the Fireflies to save Ellie, and whether any of it was worth it. Notes like these also reflect the conscious decision to tell TLOU Part II’s main story from multiple perspectives. The voices of this community prevent the player from seeing Boris solely as a father, or Clicker-killer extraordinaire, just as Abby’s story offers a corrective to our inherently biased experience of Joel from TLOU Part I.

Even the worst tropes about the way notes are used were transformed into a far more impactful experience in Hillcrest. Notes are often criticized for being little more than thinly veiled tutorials, and Part II wasn’t exempt from this: many codes for safes scattered across levels could be conveniently found on a scribbled note next door. Hillcrest is no different: Ellie discovers a note pinned to a wall with a code and an obvious location—a garage—scribbled onto it. It ends with the author complaining about Boris’ increasingly vehement opposition to WLF, which is bleeding into community hostility. On the surface, then, this note plays fully into the player’s expectations, giving them a clear objective glossed over with a little backstory flavor, thus lulling them into a false sense of security. Once they open the garage door, however, Ellie suddenly screams out. The air inside is thick with with spores, and a number of Infected rush out towards her. Upon their defeat, she shakily comments that they must have been trapped in there for years.

While this moment might seem like a well-laid jumpscare, its real significance is soon revealed. In the final note in this section, Boris confesses to killing his neighbors who conspired to turn him over to the WLF. He admits he trapped them in a spore-filled garage, and seals his own fate by doing so, when one neighbor manages to bite him. I couldn’t help but think of Joel’s final words to Marlene, and how he eventually fell to the very same retribution he’d feared. Ellie’s single word response to reading this note—”Jesus”—expresses not only horror on behalf of Boris, but also the Infected in the garage beforehand. In this moment, another few members of the faceless horde turn into all-too-human NPCs, members of a community who fell victim to Boris’ unquenchable fury. This one note, therefore, does more than coalesce with the main themes of the game; it also harnesses a growing dread of realization as the player explores, and rewards them for understanding the environment around them: something which an info-dump relegated to a scribbled note could never achieve.

The final pay-off in this story comes when Ellie meets Boris himself – in fully infected, Stalker form. As Ellie squeezes through a door, he leaps onto her, with his iconic bow still slung over his shoulder. In this moment, Ellie is confronted with the most literal, monstrous loss of humanity, stemming from an inability to pull back from an all-consuming obsession with vengeance. This stubbornness, this determination, this kind of violence which Boris enacted, is exactly what Joel harnessed to protect Ellie, and what Ellie has inherited herself. As this section sounds out the introduction to one of the darkest chapters in Part II on a hollow note, it coldly reminds both Ellie and the player what is at stake in this world, and the terrible cost of loving someone in it.

While these thematic resonances are devastating in themselves, the way Ellie herself responds to them adds one final layer of significance to this chapter. Clustering Sofia’s drawing, her graffiti, and Boris’ trophy—all of which elicit a clear response from Ellie—at the beginning of Hillcrest lets the player know Ellie’s interest is piqued by the pair. But omitting a verbal reaction to nearly all of the later notes or the level environment invites the player to imagine her response and thoughts as she explores. The fact that Ellie continues to pick these memos up subtly suggests she, too, sees the connection between her own life and the lives in these notes. Is Ellie seeking out these scraps of paper because she senses in them the same echo of her own inner turmoil that we do? Does reading about Boris and Sofia deepen her commitment to this dark path, or deter her from it?

The Last of Us Part II is about cycles, and what it takes to break them: the cycle of violence, the cycle of inherited behaviors, or more literal cycles. The backtracking, the repetition of events as you replay the game from a different perspective. These notes about Boris and Sofia showed one more set of ripples set in motion by those who choose revenge. But most importantly, they show, rather than tell, this story. These notes supplement the player’s exploration of the Hillcrest suburbs, but in a way that brings them back to the core of the game’s themes and narrative. Seeing Sofia’s graffiti and the aftermath of Boris’ vengeance, and contextualizing them through these notes, not only rewarded me for exploring, but pushed me to think further about the choice Ellie was making by continuing to go forward. With every step Ellie takes through Hillcrest, she heads for the same denouement which Boris suffered. I don’t think speaking to an NPC about Boris and Sofia, or seeing it happen, would have had nearly the same effect that slowly reading and exploring the tattered remnants of their world had upon me.

If a little more thought goes into notes – if they are weaved into the game’s world, if they have something to say about the main plot as well as other NPCs, and if they enrich the story inwards instead of endlessly spiraling it outwards – then I want to keep reading them.

Jenyth Evans (@jenythevans) is a PhD student at the University of Oxford, researching pseudohistories written in medieval Ireland, Wales and England. Asides from pondering the distant past, she is also interested in narrative design, and the mechanics of story-telling in games.