New Challenger Approaches

Joshua Trevett gets good, but slowly.

I’ve been getting into GUILTY GEAR Xrd lately, along with a small group of my friends. It’s been a long time since I’ve made a serious attempt to get okay at a fighting game, and this “anime fighter” subgenre is intimidatingly fast-paced compared to Virtua Fighter, my lifetime favorite. I’m pretty bad. At age 26 (point nine!) I’m still fairly young, but this game gives me a direct view to the inevitable wearing down of my reflexes, which is unnerving. How could I possibly keep up a flow of good decisions when the matches race along faster than I can process them?

The answer is practice, obviously. We tend to be attracted to the games we can pick up and play without too much pain, and when it comes to mechanics-driven competitive multiplayer games, that ease is a function of how much time we’ve put into similar games. It’s a bit of a self-perpetuating cycle. For me, it’s first-person-shooters: I don’t suffer too much even in the lightning-quick ones because I’ve spent so much time flicking a crosshair around that I can often make the right moves based on instinct. Even as I find less time to spend playing these games, I know enough about them to talk shop, watch those guide videos on YouTube (a guilty pleasure), and slowly improve. It’s a good feeling, so I keep playing shooters.

This relates to that old chestnut, “flow:” the supposed ideal state of play, a point of perfect balance between anxiety and relaxation. Much was written last year questioning and dissecting this concept and its primacy in conventional game design (sadly Lana Polansky’s wonderful “Against Flow” seems to be unavailable for now). Much of the takeaway from that discussion seemed to focus on dispelling the assumption that games should always be so much about mechanics, because we put games in too small a box by addressing them all as quick fixes of mastery. It’s a good point, and these days any games person worth their salt is totally on board with experiences that don’t present any obstacles at all. But what about the other side of flow’s just-right equation? If we’re rooting for those games that some might dismiss as too easy, shouldn’t we also look for value in games that are too hard?

Anyway, that’s what I keep telling myself as I struggle with Guilty Gear. I’m lousy at this game, but working up a plan to improve my skills—even if I don’t know how far I’ll get along that path—yields interesting results. We’re used to games letting us move onto the next thing when we finally accomplish whatever difficult task, but when I execute a ridiculous combo after struggling in training mode the thought sinks in: now I’ll have to do that a hundred more times.

Triangle L1 down circle up triangle square triangle up triangle quarter-roll circle. You can buffer the face buttons but not the directions. Even when the muscle memory starts to settle, the problem of the combo continues to blossom into deeper complexity. When to set it up in a real match? How to adjust it for lighter or heavier opponents? Which parts of the sequence can come in handy during other scenarios? Performing the combo once against a dummy is nothing, the important thing is building a repertoire of instincts so that I’ll eventually act a step ahead of my thoughts.

The whole thing reminds me of when I was a kid learning to play the trumpet. Back then, I hated practice—the way my lips would ache as I played and replayed the same tricky passage of music, the sound of my spit clearing the valve and hitting the floor. Every tiny facet of the experience was amplified into loathsome intensity by the sheer tedium of the process. But it doesn’t have to be that way! Intense experiences are worth savoring, at least as long as they aren’t actually harmful.

What I’d like to internalize is that my time spent training in Guilty Gear has aesthetic value to me, even if it never ends up having been enough time to achieve competence. There’s something majestic about the enormity of the task, and just because I may never reach that mountain’s peak doesn’t stop it from being quite a sight from down here at base camp. To climb just some of the way up reveals something about what it means to reach the top.

For its part, the game makes the journey as tolerable as it ever could. Its 3D models that masquerade so convincingly as 2D sprites make it a visual feast, and I dig the way the camera spins freely around a final freeze-frame of each bout. I keep wishing I could unlock the camera and view the action from different angles just to drink in those animations and character models, and the freeze effect satisfies that urge for a fleeting moment and releases the tension of the fight. Win or lose, a perfect-looking finish is always something to appreciate.

The game’s writing, outside of its utterly inaccessible story driven by a mess of unseen villains and other proper nouns, also has a reassuring presence. This plot has been going on for almost 20 years, and a large portion of the playable characters have by now become good buds or friendly rivals. That’s a bit problematic for a fighting game narratively speaking, but it does give many of the fights the feeling of a sparring match between comrades—it’s rare to encounter any hint of malice in the tone.

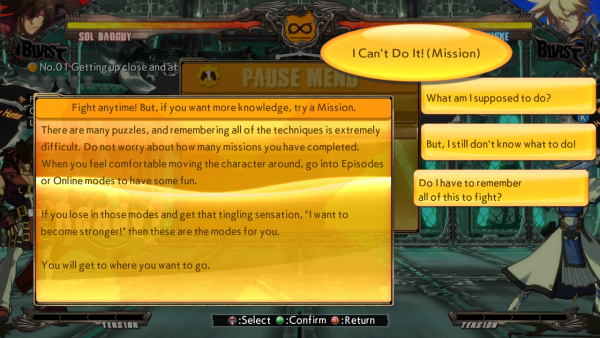

Of particular note is the uplifting attitude of the tutorial modes and FAQ section. Not only are they full of thorough advice presented briskly and clearly, they do their best to frame the player’s mindset positively. For example, take a look at this lovely message offered to reassure frustrated players.

“You will get where you want to go.” That sentiment really has a way of lingering warmly.

So, am I older and more ready to submit to the hard work of learning unfamiliar skills than I was when I thought the trumpet was a dull obligation? Or is this slick cartoon videogame just greasing the wheels for me? It’s hard to say, but I’d like to hope there’s some value in committing to this process—grit is grit, whether it’s applied to something with real-world value or not. I reckon it can be exercised like any muscle.

Serious offer: get in touch with me, join our little fight club. We play –SIGN- and –REVELATOR- on the PC.

Joshua Trevett is a freelancer and the managing editor of Haywire Magazine. He mostly likes art when it’s weird, and that goes double for videogames. For secret reasons, it would be best if you followed him on just two out of these three social media sites: Twitter, YouTube, and his blog.