My beautiful dark twisted product design fantasy: Design-first thinking in Block’hood and beyond

S.P. Myers moves slow and doesn’t break anything.

In the face of climate collapse, it can feel therapeutic to lean into a clean systematic approach of balance. Because balance is a cleaner and more parseable goal when one is looking at a blank, open field, this can mean wiping clean complications in order to focus on the pure mathematics of something like the greenhouse gas equivalencies calculator. When there are no pre-existing variables, the goal is simply a matter of balancing out anything added. This all feels great, but it runs the risk of leading you to a conclusion that doesn’t actually reckon with the messy issue at hand.

The narrative of the story mode and the central push behind Plethora Project’s 2016 city-builder Block’hood is to encourage people to think of new ways to balance human needs with nature. However you define it, nature is not a blank slate. To account for this, and to bring the player into that therapeutic clean slate, Block’hood employs some subtle, yet telling, mechanical meddling with the math behind the balance. In its open-world sandbox mode, players are given a large square of nature that they can first fiddle with and adjust based on biome and terrain, then build on and balance out ‘hoods. When the player first begins building on a section of their open world, the environment is generated and a few animals populate it. When you select a block in the pre-generated environment, the outputs and inputs are a simple .02 groundwater needed and .02 fresh air generated. This is in stark contrast to both the organic and inorganic blocks that the player can place. For instance, an oak tree requires 1.2 groundwater and generates 1 fresh air, 2 wilderness, 1 leisure, and .6 acorns. This is all to illustrate that the built environment that the player engages in creating in Block’hood is more dynamic and complex than the pre-established natural space they are given to build on.

A domesticated oak tree’s inputs and outputs compared to the native highland taiga’s.

This privileging of personal creation over its environment is part of what can be called design-first thinking, which has existed in one shape or another for a long time outside of Block’hood. I think a valid argument can be made that it has cohered as a way of thinking in Silicon Valley’s product design ethos. In Make It New: The History of Silicon Valley Design, Barry Katz traces a similar form-before-function thought process to the design of the HP-35 calculator, which, way back in 1972, prioritized the design of its pocket-sized chassis over the capabilities of its internal components. In this case, the outside-in approach paid off as pocket calculators found success, but somewhere along the line, putting design first seems to have become the prevailing approach for tech companies inside and out of Silicon Valley, to varying degrees of harm.

Before going on to orchestrate the disaster of medical malpractice and investor fraud that was Theranos, Elizabeth Holmes had the idea for a dermal patch that could administer antibiotics faster and easier than taking a prescribed regimen of pills. When she took this idea to an advisor at Stanford it was dismissed based on the fact that antibiotics need to be administered at a larger scale and over a longer period of time than a patch could allow. Similar criticisms about the impossibility of small scale design would later be levied against the toaster oven sized blood-testing Edison device she became famous for. Both Holmes’s initial idea for an antibiotic patch and her blood testing device put form before function and privileged her own design over medical realities.

On the lighter end of this spectrum, this way of thinking led to the Juicero, a countertop juicer of the future that purported to give its users fresh juice every morning by applying four tons of force to bags of fruit pulp. After going to market, it was quickly found that the Juicero could only apply about as much pressure as a writer for Bloomberg Business could by squeezing it with their hands. It turned out to be a $400 bluetooth enabled Capri Sun Keurig and went belly up pretty fast. I’m jealous of people who have had the luck to find them in Goodwills. It was design-first thinking that did the Juicero in, because, well, just look at it. Does a primarily plastic appliance applying pressure sideways look like it can produce four tons of pressure? The look of the appliance and its place in the kitchen came first. What it could actually do came second.

Design-first thinking becomes most dangerous when it finds its way out of the number crunching, systems-based world of designing consumer products and into the messier, harder to systematize social world of human wellbeing, which is why Juicero is mostly just hilarious and Theranos is more complicated. As this aspirational way of thinking has become mythologized, it has consequently slipped out of the design world with goals like Steve Jobs’ desire to have 1,000 songs in your pocket finding allies in self-help new spirituality and broader moralizing about the virtues of capitalism in the 21st century. When it all combines together, it aligns with what Cameron Kunzelman, in a recent episode of Game Studies Study Buddies reviewing Brenda Laurel’s Computers as Theatre, calls the “California ideology.”

Kunzelman uses the term to describe Laurel’s overarching aspirational optimism towards how technological innovation and the entrepreneurial spirit can be humanity’s salvation, which becomes most apparent in the epilogue she wrote for the book’s second edition. Laurel writes:

Well friends, we are living in an entrepreneurial time. Elon Musk … will go to Mars because he is making it so. People with a lot less wealth than Musk have funded companies to do the right relationship building with investment by regular people through tools like Kickstarter and Indie Go Go. ‘Well it’s hard,’ designers tell me. It’s hard to create a product or technology with the intention of cultural intervention when it goes against the tropes of popular culture. To those I reply, people have done these things. … Yes it’s hard. Virtue is hard. Gaia citizenship is hard. Suck it up. Get to work.

Just like design-first thinking can work for everyday consumer products but not necessarily medical equipment, Laurel’s optimistic California ideology becomes most worthy of critique when it turns away from systems-based game design and towards the messier humanity-scale issue of climate change. As Kunzelman puts it, “the hard thing is to bootstrap yourself out of climate collapse.” He goes on to reflect the contradiction at the foundation of the belief system; “Let’s just use the system we live in to liberate ourselves from the system that produced the condition we live in.”

Kunzelman’s critique has connections to larger conflicts between material change and revolution versus discursive moralizing and reform that can be found in most social movements. In environmental movements it can be seen in the fight against Green Capitalism and greenwashing, which opt to put a new coat of paint on pre-existing marketing schemes instead of democratizing or reinventing markets and industries to give power to the people affected by the changing climate. His final outline of the issue reminds me of the famous Audre Lorde quote, “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” although she is focused on systemic racism (which notably intersects and weaves with climate collapse as industries offload the worst consequences onto minoritized groups and the global south).

This is the unreckoned with and unsolved contradiction I feel when I answer the call to balance the wants and needs of nature with the wants and needs of humanity in Block’hood.

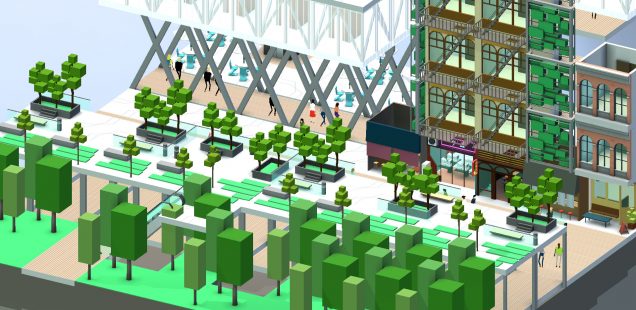

Aesthetically, Block’hood wears its California influence on its sleeve. Players are quickly greeted with the white, boxy, Hardie panel constructions of living spaces that form the center of the game’s aesthetic sensibility. This aesthetic runs parallel with the gameplay’s reliance on the unit of the 1X1 cube and sometimes 1X2 rectangular prism for its stacking mechanic. The one-aesthetic-fits-all modular sensibilities of new construction fits with the therapeutic sensation that the system can work and the pieces can all fit together.

Right next to the satisfaction of a square peg fitting in a square hole is the aforementioned mechanic of balance as the player is asked to balance the costs and benefits of both nature (i.e. fresh air and groundwater) and humanity (i.e. community and beer). When I would first tell friends and strangers about the game I would pitch it as “Sim City but you can listen to the animals too.” In this way, it does successfully decenter the human, but doesn’t decenter the idea that both humans and animals can live under one managed system. Additionally, people and animals show up like window dressings after buildings have been placed, meaning the design is required to come first. As a result, the people and animals feel like achievements that come from designing a good enough system, as opposed to active participants in creating, maintaining, and adapting that system in the first place. Just like the reduction of native tiles to simpler inputs and outputs turns nature into a blank slate, the secondary nature of your residents keeps the math clean and removes messy variables.

Iwalani the street performer only arrived after building a jazz cafe and a plaza for them to perform in.

Block’hood furnishes a kind of climate therapy gameplay by framing these systems and aesthetics within a short storyline that centers on the life of an urban developer. The developer starts out as a kid exploring nature, talking to a warthog he names Parker and planting chestnut trees to attract more friends for the warthog. As missions progress and begin to involve more and more human concerns, the protagonist slowly forgets how to hear Parker and becomes completely absorbed in creating a human-focused environment filled with sweatshops, factory farms, and electronic waste. The protagonist is only able to hear Parker again after the community he is planning collapses from too much waste and too much discontent.

The morality tale of being led to ruin by consumer capitalism that doesn’t pay mind to nature is worthwhile, but risks putting the player in a position to moralize themself into the one who speaks for the trees while giving them the satisfaction of getting the system to work just right. That self-protagonizing combined with systems-based thinking isn’t far from where Holmes’s head was most likely at when she spearheaded Theranos towards its eventual collapse. This headspace gets you thinking that you know how things are supposed to fit together. It gets you thinking that a system can be perfect even if it doesn’t account for messy humanity.

In Critique of Everyday Life, Volume II, spatial sociologist Henri Lefebvre uses the metaphor of a seashell and the organism inside to illustrate the dialectic of the systems we become enamored with and the sticky, squishy beings that create them from need in the first place.

I pick up an empty seashell on the beach; I examine it; I find it beautiful, fragile, perfect in its way, and it satisfies my mind like a materialized Idea. I see that it is endowed with a prodigiously delicate structure: symmetries, straight lines and curves, grooves and ridges, lobes or spirals, serrations, etc. … I am lost in admiration. I decide to describe these structures carefully and to use them to learn about the living beings these shells once contained. An excellent method, since the shell is there, in my hand, stable, solid and precise. … If I find that living being in another shell similar to the one I have picked up, I will see that it is soft, sticky and (apparently) amorphous; taken out of its shell, how different the two are! And yet it is the shellfish which has secreted the shell; it has taken on the form of the shell; it has given itself that form. … Part of the process of becoming and yet eluding it, the shell – a product or a work made by life – is not alive.

The beauty of the dead shell and the ease of observing and displaying it are part of the satisfaction of Block’hood and the draw of the California ideology. You wouldn’t put the living meaty clam inside a jar and put it on a shelf in your beach themed bathroom. Similarly, it may be harder to create a therapeutic and satisfying game out of wrestling with the full breadth of creating a society that can mitigate climate change and thrive through its coming consequences. It’s comforting to look at the parallel lines of a clam shell the same way it’s satisfying to watch Steve Jobs as played by Michael Fassbender resolutely declare that “it needs to say ‘hello.’”

By having its players place sleek, sterile structures first, then having residents move in second, Block’hood is placing the seashell first and its organic occupant second, despite the fact that the seashell wouldn’t exist without the organism in the first place. It’s a subtle conflict that other city builders like Sim City and Cities: Skylines (both of which smuggle in their own ideologies) seemingly conceal by putting the player in charge of zoning instead of building. This difference gives some mostly aesthetic and partly mechanical agency to the residents and businesspeople of the city who choose what exactly to put in those zones. The gooey organisms get to make their shells. At least on paper.

To their credit, Plethora Project’s new game Common’hood seems to meet my critiques of Block’hood head on, as the perspective has changed from a top-down to a ground level view and the people who occupy the space being managed – an abandoned factory – seem to come first. I can’t wait to play it.