Games are the Most Personal Thing

Riley MacLeod talks to Cara Ellison about how to be important.

Over the last few weeks, I’ll find myself saying something in conversation with other writers and then admitting, “Oh, Cara Ellison told me that.” We’d been at a few games events together over the years, at which I usually demonstrated my long-standing admiration by maturely running away and hiding. Last spring I found myself crammed next to her in a crowded Shake Shack, attempting to eat a burger as fastidiously as possible and hoping she wouldn’t ask me what I did so I wouldn’t blurt out, “Oh my God I’m a writer too—how the hell do you do it?”

Now, in conversation over Skype, Cara admits, “I don’t know how I did it. I just try to write something raw and human that nobody else is writing, but I really don’t know what that is.”

We’re talking about Embed With, her forthcoming collection of essays recounting the year she spent travelling the world, staying with different game developers and reporting on their lives. The project started as a Patreon-backed blog before being collected into an ebook. Recently it was picked up by a publisher and is set to come out in print this fall.

“A lot of people see it as a kind of history of what was happening in independent games in 2014,” Cara explains. “People consider it a kind of history book, so they want to own it and put it on their shelves.”

In many ways Embed With is history, detailing the careers of people like Tim Rogers, Katharine Niel, Harvey Smith, Liz Ryerson, Brendon Chung, Nina Freeman, and a host of others. But, as Kieron Gillen says in the introduction, it’s also “a time capsule to show what it was like to live through This Turbulent Year in Games… This is what it was like for us.” It isn’t a history in the sense of names, dates, and places; it’s a record of an emotion, a love letter to the drive to create and how to make space for that in your life. The world bangs around in the book, as Cara situates each subject firmly in the messy, unique context of their lives. In her usual personable, honest style, she pins down the weird heart of being a person who makes things, showing how her subjects’ craft seems to undergird and frame every aspect of their lives, even when they’re eating fast food in a car or shouting over the music at a pub.

In many ways Embed With is history, detailing the careers of people like Tim Rogers, Katharine Niel, Harvey Smith, Liz Ryerson, Brendon Chung, Nina Freeman, and a host of others. But, as Kieron Gillen says in the introduction, it’s also “a time capsule to show what it was like to live through This Turbulent Year in Games… This is what it was like for us.” It isn’t a history in the sense of names, dates, and places; it’s a record of an emotion, a love letter to the drive to create and how to make space for that in your life. The world bangs around in the book, as Cara situates each subject firmly in the messy, unique context of their lives. In her usual personable, honest style, she pins down the weird heart of being a person who makes things, showing how her subjects’ craft seems to undergird and frame every aspect of their lives, even when they’re eating fast food in a car or shouting over the music at a pub.

“It’s a book about writing, and a book about my own struggle about what being a writer is, who I am, and what my role is,” Cara reflects. “In the beginning I thought it was super great that I got to travel and write; that was always what I wanted to do, what a brilliant idea… But what I’d set out to do was basically live in other people’s minds 100% of the time, and that meant working 100% of the time and never switching off. And I knew I was going to leave every month and the bonds I had made would disappear—I was deliberately severing ties every month. A lot of the time I was surviving on this contact high, and being that way is so psychologically hard. I was basically just self-flagellating the entire time, going ‘what did you think was going to happen? This is stupid; why did you do this?’ I knew I’d have to pull myself away, so it was really isolating.”

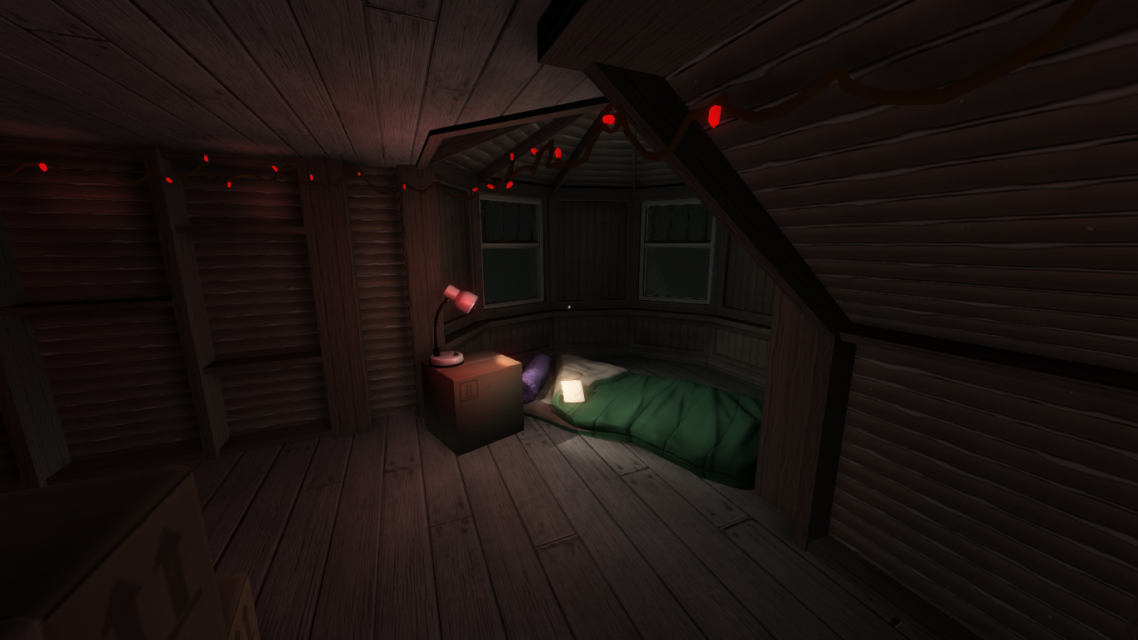

The toll the project takes on her, both positive and negative, is a unique theme that runs through the book. But for every moment of exhaustion, doubt, or struggle, there are small, beautiful moments of community, joy, and triumph. We see George Buckenham and Alice O’Connor pull off London’s Wild Rumpus; we watch Cara make sandwiches with Adriaan de Jongh. Blurry photographs capture this casual, living feel, but they aren’t the images of coders sitting behind keyboards that we so often see in documentaries about game developers. Instead, there are bodies on couches and in beds, hovering over coffee cups and half-eaten meals, existing as grainy blurs in cars and doorways. In fact, many of the book’s most memorable and affecting moments have nothing to do with actually making games at all; they come from the interactions between people living lives that make room for creativity.

“When we look at the golden era of Rolling Stone gonzo journalism, when people went to stay with musicians and stuff, what readers really wanted had nothing to do with the music,” Cara says, favoring the decision to talk about gamemakers rather than game-making. “They really wanted to read about what these people they really admired thought and what they were doing with their lives outside of music. Obviously they get the end product, but that isn’t eventually that important to people. What was important was ‘how did that person get there?’ and ‘why did they do it?’ and ‘what is their life like that they can produce this amazing thing that I really like?’ I think eventually I realized that people did actually want to know the creative process of the people who make the games that they really like, because that, in some ways, is very inspiring and very human in itself.

“When we look at the golden era of Rolling Stone gonzo journalism, when people went to stay with musicians and stuff, what readers really wanted had nothing to do with the music,” Cara says, favoring the decision to talk about gamemakers rather than game-making. “They really wanted to read about what these people they really admired thought and what they were doing with their lives outside of music. Obviously they get the end product, but that isn’t eventually that important to people. What was important was ‘how did that person get there?’ and ‘why did they do it?’ and ‘what is their life like that they can produce this amazing thing that I really like?’ I think eventually I realized that people did actually want to know the creative process of the people who make the games that they really like, because that, in some ways, is very inspiring and very human in itself.

“That became really important to me,” she goes on. “Realizing [creators you admire] are human is a really good way to stop thinking about creativity as if it’s something you personally can’t do. We have all these deities of our creative world where we think, ‘oh, I could never create a thing like that person did,’ but I think part of realizing that you can is actually just going to talk to these people and understanding that they don’t have any kind of supernatural ability.”

To me, this is a powerful statement. I think we lose something when we see creativity as a mystery only a chosen few have access to, when the process of making quality work becomes summed up as a magic too scarce for everyone to share. Cara and I discuss how making things, be it writing or games, takes practice and hard work—and okay, maybe a little bit of magic. “There are parts of it that are magic, and there’s the other side, which is a job. John Cleese did this talk about creativity that basically said the way you become a creative person is that you create a space to play in. When you start to consider play being a kind of work a lot of things make sense. For me, the idea is that you need to leave space for the magic to happen,” she laughs. “I’m starting to consider that there is a core of magic to writing and creativity, but getting there is the work.”

Cara’s own journey to “getting there” has been one of change and growth as both a writer and a person. “Games journalism is a weird thing, but I think people appreciate really great writing. It isn’t without reward, and I would love to tell my 12 year old self that. Particularly in my early days of journalism I was very open rib cage, but I was trying to cover up my nervousness about something with humor, by being silly. I got more sincere over time. There’s a kind of earnestness to my voice now that has become more intense—now, when I crack a joke, it’s more sincere.”

Another turning point in her work, she continues, has been changing the way she reflected on her impact. “I don’t know if it’s useful to think about your work being important. Halfway through last year I started to realize I didn’t care if anyone thought what I was doing was important or not because I was so fulfilled by what I was actually putting out. I started out to write something important about games, but now what I really care about is that I like it. The people I write it for like it, but most of all me. [I became] more humble, and maybe that’s making me a better writer. I stopped striving toward being important all the time because that was detrimental to my work… I think in terms of work, you should start to understand that the importance will probably come.”

Along with this evolution came a growing understanding of how to present herself to an audience. “I had to be very careful not to write defensively. I realized halfway through my journalism career that if you start to write an essay against what you know will be written in the comments it starts to become a really nasty piece of work because all you’re doing is fighting the commenters before they’ve got there.

“I [also] almost fell into this trap, at the beginning at least, of feeling like I had to bring up the fact that I’m a woman,” she says, talking about the ways in which writing from a personal perspective could both welcome and alienate certain readers. “I ended up writing about parts of my life that were implicit signals of my life experience as a woman, which welcomes women readers and signals that it’s a safe space. I spoke directly to women readers, and they ended up reading my work more frequently… [And] there isn’t a way that you can get away from your identity. If I don’t just write what I think then I’m betraying myself.”

This combination of openness and writing for herself has garnered a positive response from her readers and supporters, many of whom are writers or developers themselves. She tells me a lot of people wrote her to say, “Thank you so much for writing this; I really needed to read this today. I felt like I was failing, but it’s nice to know that someone else in the world is struggling with this. Maybe I can make something too.”

This combination of openness and writing for herself has garnered a positive response from her readers and supporters, many of whom are writers or developers themselves. She tells me a lot of people wrote her to say, “Thank you so much for writing this; I really needed to read this today. I felt like I was failing, but it’s nice to know that someone else in the world is struggling with this. Maybe I can make something too.”

For me, this “me too” is the heart of the book. In translating between writers and game developers, the journalist and her words, and people’s lives and their creative output, Cara turns both making games and games writing into a kind of mundane magic. Creativity and talent aren’t things that are handed down to us from on high, but rather something we pull out of ourselves and offer to others, something we can hone through hard work once we have the willingness to be open to it and to be open to ourselves.

“Games are the most personal thing,” Cara concludes. “Hopefully you can start to see exactly why each person makes the games that they do. All these people are creating things through hard work that enriches people’s lives and helps them think about things in a new way. I think people need a reason to get up in the morning, and people who create things create that reason. [The people I interviewed are] so human, and that’s helped me realize I might not be too far away from the things they’ve created. If them, why not me?”

Riley MacLeod is a freelance writer and editor whose work has been seen at The Border House, Relevant Magazine, and Lambda Literary, among others. He is the former editor of Topside Press, a small press fostering new voices in transgender fiction. You can follow him on Twitter.