Bloodborne Makes A Beast Out of You

Harry Mackin explains how Bloodborne gets rid of the pain of being a man.

Spoiler Warning: This article contains spoilers for the plot and endings of Bloodborne.

Most action RPGs follow a gameplay loop that could be described as colonial. You’re an outsider in a hostile world, and you advance by overcoming threats, gaining power and taming territory in the process. The plot coordinates with the gameplay; you start as an up-and-comer and become more important to world events as you gain power. RPGs are about mastery—as the player masters the gameplay systems and overcomes challenges, the player character masters their power and their environment.

This framework is so ubiquitous that players are conditioned to interpret Bloodborne through it. In fact, the impact of Bloodborne–upon the player and the genre itself–relies in part on these preconceived notions. Like other action RPGs, Bloodborne’s plot and gameplay coordinate to convey an idea. However, most RPGs want to make you feel like you are having an effect on the world. Bloodborne, on the other hand, is about subverting that idea. Instead of focusing on what you are doing to the world, Bloodborne is about what the world is doing to you.

Prophetically, the inciting incident in Bloodborne involves the player character taking a part of the world into themselves. They enter Yharnam, the city where Bloodborne unfolds, chasing a rumor that a transfusion of a legendary substance found on in Yharnam called “Paleblood”, which can apparently cure their fatal illness. This “Paleblood” comes at a cost: in order to receive the transfusion, the player character agrees to become one of Yharnam’s “hunters.” Without understanding how or why, the hunter-character receives strange powers to use in service of a mysterious purpose not yet clear to them.

Early on, it becomes clear that a substance called “Old Blood” is central to unraveling the mysteries of Yharnam and the Hunter’s purpose. When Yharnam’s healing church discovered Old Blood transfusion, its citizens became obsessed with it and addicted to it. Yharnam’s factions of scholars, doctors, and fanatics made the Old Blood central to their practices. Seeking to unlock the Old Blood’s secrets, they performed increasingly elaborate and disturbing experiments on themselves and others.

Bloodborne makes the player understand and even sympathize with Yharnam’s dark fascinations. From the jump it is obvious that Yharnam was not constructed “for” you. There are no tutorials that teach you how to navigate your environment, nor quests conveniently waiting for you to activate them. The world is packed with the unknown; everywhere you turn there are strange artifacts, rituals, architectural wonders, and elaborate machines, all hinting at some great purpose you don’t yet understand. Twisted statues guard abandoned chapels. Coffins sealed with chains and locks line the twisting streets. The mangled corpse of some incomprehensible creature burns on a crucifix above an *ahem* bloodthirsty crowd.

You do not colonize Yharnam; enemies will always be waiting to ambush you, and Bloodborne’s difficulty ensures you never feel safe. You unlock shortcuts and checkpoints along the way, but even these do not feel like you’re leaving your mark. The checkpoints are lanterns left behind by older hunters. You have no agency in their creation, you simply turn them back on. Unlocking shortcuts is usually the simple process of unlocking a door or learning about a hidden passage. You aren’t changing the environment to suit your purposes, you are merely learning how to better traverse the existing environment–in other words, you adapt yourself to your environment.

Even the role and motivations of you–as “the hunter”–are kept out of the player’s reach. Bloodborne supplies very little in the way of plot. You learn that hunters never truly die, instead returning to the Hunter’s Dream, where they can set out to hunt the beasts of Yharnam again. Gehrman, “the first hunter” and the closest thing the game gives you to a mentor, tells you to hunt the beasts “for your own good.” He leaves it to you to interpret what that means.

All of the Old Blood use in Yharnam is motivated by a desperate craving for knowledge. This craving reflects and parallels the hunter-player’s own desires to learn more about what’s happening to them and what they’re supposed to do. Blood passes a kind of either wisdom or madness to its user. Upon introducing the Old Blood into their bodies, the people of Yharnam seemed to experience bizarre and horrible visions of the “true” nature of the world. As more Old Blood was consumed, these visions became more like reality. Eventually, it seemed as though the world revealed by Old Blood was the real world; one humans were incapable of seeing before. The knowledge promised by these visions was so compelling that Old Blood use continued even as the blood’s curse transformed its users into beasts. As the player hunts for knowledge of their own, they transform, too.

Bloodborne invites player interpretation with every element, from its gameplay to its worldbuilding. Like the Souls games that preceded it, you learn most of the “plot” of Bloodborne in the flavor text of the items you acquire. Virtually every item in the game has a description that hints at the greater mysteries of Yharnam. Some of these items, like the Blood Vials you constantly inject into yourself to heal, imply ominous information about the downfall of Yharnam:

“Once a patient has had their blood ministered, a unique but common treatment in Yharnam, successive infusions recall the first, and are all the more invigorating for it.”

Others, like the description for the Threaded Cane, give us a glimpse into the mentalities of various factions within Yharnam and–just maybe–into the player-hunter’s psychology:

“Concealing the weapon inside the cane and flogging the beasts with the whip is partly an act of ceremony, an attempt to demonstrate to oneself that the bloodlust of the hunt will never encroach upon the soul.”

Bloodborne’s worldbuilding is not impartial or even entirely trustworthy. The game’s world has an agenda: Bloodborne wants you to actively interpret the information it drip feeds you in order to lead you toward certain interpretations about Yharnam and your place in it. All the flavor text in the game strategically hides, twists, or other obfuscates exactly what it means in order to suggest one theory or another.

In other games, learning more about the world as you master it feels like an extension of the gameplay’s colonial overtures. Just as the gameplay leads you toward mechanical mastery, the lore leads you toward a narrative justification of that mastery–a conclusion you see coming. You’re the chosen one, you’ve fulfilled a prophecy, etc. Bloodborne’s lore and gameplay coordinate to lead you toward a conclusion, too, but that conclusion is a trick. Bloodborne knows you want to know more about why you’re doing the things you’re doing, and it uses that desire against you.

The interpretation the game seems to want you to come to isn’t difficult to figure out. The player is meant to surmise that the hunter is the latest in a long line of Van Helsing-esque characters: they hunt beasts to purge the world of something that shouldn’t be. The game mischievously encourages this interpretation. Flavor text and conversations imply a sort of zealous holiness to the hunter’s quest. Consider the Kirkhammer, another one of the many weapons you can acquire:

“A trick weapon typically used by Healing Church hunters. On the one side, an easily handled silver sword. On the other, a giant obtuse stone weapon, characterized by a blunt strike and extreme force of impact. The Church takes a heavy-handed, merciless stance toward the plague of beasts, an irony not lost upon the wielders of this most symbolic weapon.”

Arguably, the more experience the player has with either RPG or horror conventions, the more intuitive this “Holy Zealot” theory seems.

As you learn more about the world of Yharnam, however, the game gives you reason to doubt whether you’re the dutiful protector you think you are. It feels less like you’re performing a duty and more like you’re being driven by your fascinations. You wouldn’t realize it at first, for instance, but many of the areas and bosses in Bloodborne are optional. Finding every boss in the game takes considerable effort going out of your way. If your purpose was really to wipe out the Yharnam threat, why would you be able to overlook so many of its monsters? If Yharnam has been condemned and all its citizen transformed, who exactly are you saving by hunting down the monsters cowering in its remote corners?

Furthermore, you don’t seem to receive any reward for your hunts, except more “Blood Echoes”, a resource you gain from killing enemies which you use to become more powerful (and, the game makes clear) monstrous. As you play, you’re literally incorporating more and more of Yharnam into yourself. Your character’s appearance tends to become more fearsome and beastial as you acquire more powerful equipment. Even the mechanics of Bloodborne’s gameplay encourage the player’s fascinated knowledge-seeking. And just like the ill-fated citizens of Yharnam learned, that knowledge comes at a price.

The gameplay loop of Bloodborne is, infamously, determined by persistent trial and error. Just as the plot of Bloodborne revolves around an obsession with knowledge, the player becomes obsessed with learning in order to advance. The only reliable way to defeat enemies, especially the many monstrous bosses, is to study them. By the time you beat a boss, it’s because you understand that boss. Even navigating through the environment itself becomes a learning process. In order to get from one lantern to the next, you have to memorize where the enemies are, find the optimal route through various traps and ambushes, and have a plan for dealing with the various threats you’ll encounter along the way.

The importance of knowledge is made even clearer by Bloodborne’s most unique mechanic. As you proceed through the game you constantly collect a resource called Insight. You can gain this resource in various ways: you get a point for discovering a new area within Yharnam, one for seeing a boss transform into their “true” form, and another for defeating that true form. You gain several for consuming an item called “Great One’s Wisdom.”

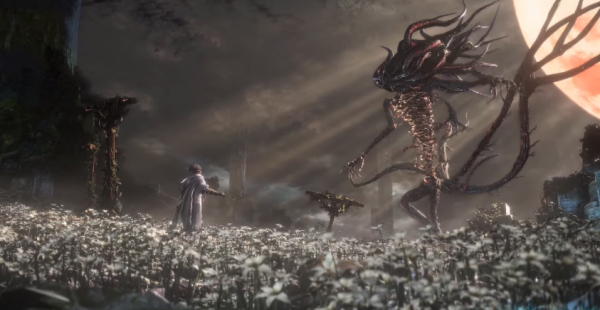

Insight serves both a mechanical and thematic purpose. You spend Insight points to become stronger, and you gain Insight points from discovering the various secrets of Yharnam. Literally, the more you learn about Yharnam, the more powerful your character becomes. Gaining Insight also changes the way the world itself appears to you. It starts subtly; when you first gain Insight a doll in the Hunter’s Dream comes to life. As you gain more Insight, the changes become even more pronounced, and begin occur outside the Dream. Early on, it’s easy to assume the Insight is making your character hallucinate. Gain enough Insight, and the hunter-character will hear disturbing noises everywhere they go and new enemies will begin spawning in previously explored areas. After a certain story event, the hunter sees Yharnam’s true form–the form its citizens see. A blood red moon hangs ominously in the sky and alien creatures with reality-shaping powers loom over the city. Seeing the city under the blood moon, and the new enemies triggered by it, confirm that the Insight is just that: insight. It wasn’t that the player-hunter was seeing things that weren’t there; for the first time, they were seeing things that were always there.

As both the player and hunter’s knowledge peaks, it becomes more possible to infer the true cause of Yharnam’s madness. The Old Blood is the product of experimentation concerning the Alien creatures which were summoned and become visible with great Insight. By transfusing their own blood with the blood of these “Great Ones,” the scholars of Yharnam hoped to transcend the natural limitations of humanity. One of the game’s final (and few required!) bosses, “Micolash, host of the Nightmare,” speaks of acquiring “eyes on the inside” in order to ascend to a higher plane. To Yharnamites, Blood and Insight became a way to see the world for what it *really* is and evolve into God-like beings in the process. Ultimately, the leaders of Yharnam hoped to usher in a new chapter for humanity by impregnating a woman with a Great One’s child, as evidenced by the “One Third of the Umblical Cord” items the player finds if they search hard enough. These attempts failed, and brought about the events that the hunter was ostensibly tasked with undoing.

None of this is ever made explicit. The ultimate fate of the hunter is determined by the actions of the player. Like many action RPGs, Bloodborne features multiple endings. The ending the player-hunter receives is determined by their actions throughout their “hunt” and by a series of decisions in the endgame. In most action RPGs with multiple endings, there is one “True” ending. This ending is generally agreed to be the “true” ending, and attaining it is usually more challenging or requires more effort. The truth is considered a reward for player committed enough to the game to see it through all the way.

Like with everything else it borrows, Bloodborne only plays the “true” ending convention straight to a point. Bloodborne’s true ending involves completing an appropriately esoteric ritual which it alludes to very little. The only way the player could get this ending is if they explored Yharnam as thoroughly as possible–and, consequently, incorporated as much of Yharnam into themselves as possible. Where other games would reward the player for their commitment with a true ending that felt more conclusive or validating, however, Bloodborne’s true ending does something else: it reveals the game’s grand trick.

In order to get the true ending, you have to find and consume three “One Third of the Umbilical Cords.” These are the final product of Yharnam’s failed attempts to produce an infant Great One. The hunter receives one for defeating “Mergo’s Wet Nurse,” one of the possible final bosses. To find the other two, the player has to go out of their way to find hidden areas and complete obscure quests. In other words, to get Bloodborne’s true ending, the player must demonstrate not only gameplay mastery, but some understanding of the logic behind the narrative. Also, they have to “consume” umbilical cords. Which doesn’t seem like a normal thing to do.

Consuming three Umbilical Cords unlocks the real final boss, a giant Great One called “Moon Presence” that created the Hunter’s Dream and controls the curse afflicting the player-hunter. This God-like “Moon Presence” is the kind of Great One the scholars of Yharnam became obsessed with turning humanity into. Their failed experiments and rituals were ultimately attempts to create a Great One-human hybrid that could become as powerful as the Moon Presence is.

After defeating the Moon Presence, the player-hunter is covered in its Blood, and Bloodborne’s final cutscene begins almost immediately. The Living Doll that helped the hunter is standing over what appears to be a small slug. The Doll asks the slug “are you cold?” before picking it up and swaddling it like a baby. She comforts it by softly cooing “Oh, good hunter.” This ending is called “Childhood’s Beginning,” and the achievement you receive reads: “You became an infant Great One, lifting humanity into its next childhood.”

The true purpose of the Hunter’s Dream and the hunter themselves was to finally succeed where Yharnam failed. Bloodborne exploits the player’s preconceived notions about their role as protagonist of an RPG; in the True Bloodborne ending, you bring about and become exactly what you were ostensibly created to oppose. The hunter’s journey to kill the beasts, gain Insight, and complete the Hunter’s Dream wasn’t to “set right” the dark rituals begun in Yharnam. It was to complete them. The tools the player assumed existed to help them–the Blood, the Insight, the Hunter’s Dream, even the Doll herself–had hidden agendas of their own. Instead of being the primary agent in Bloodborne’s story, the player is a pawn in a scheme beyond their understanding. The greater the player’s “mastery” of Bloodborne, the greater the game’s mastery over the player.

Instead of the power fantasy players are conditioned to expect, Bloodborne forces the player to confront what those expectations mean about us. When we consume media, what is that media doing to us? What does it mean to “master” something? How does the process of “mastery” change how we think about what we’ve mastered, about who we are, or about the agency we possess? What are we really doing when we put ourselves into something? What are we doing when we take something into ourselves? According to Bloodborne, the actions we undertake affect us at least as profoundly as they affect anything else. When we change something, we change ourselves, too. When we colonize, we are colonized. Bloodborne isn’t disquieting because of something we see in it; it’s disquieting because of what it shows us in ourselves.

Harry Mackin is a freelance writer from Minneapolis, Minnesota. He has been published by Game Informer, Paste, Playboy, Thumbsticks, and Unwinnable. You can find him on twitter at @shiitakeharry, and more of his writing on harrymackin.com.