Blank Slate

On multiple choice narratives.

If you’re unphased by spoilers or have already played the game, I encourage you to go read Andrew Huntly’s thoughts on The Walking Dead’s 400 Days expansion. I wanted to share some of my own in response today, not because I disagree, mind, but because the subject of multiple choice narratives is very near and dear to me. Andrew captured fairly precisely the things that bug me about the game, but it’s still clear that we see matters quite differently, and that the things that bug him bug me to a far lesser extent, or not at all.

To be precise, I can’t say that I see the game’s brevity and sparse nature as a definite weakness. Both are handled rather clumsily at times, and perhaps comparisons to the well-written and well-defined characters of Season One are more fitting than I care to admit, but it doesn’t irk me that the five protagonists of 400 Days never get to show us their actual identity, in his words, because I don’t think that’s what the game is trying to do, for better or worse.

Rather than introducing us to fully fleshed-out characters, it gives us leeway to define them ourselves in a quite substantial fashion. It’s almost a kind of improv acting: You are cast into this role (are roleplaying, if you will), get a few cues, then bounce off those, fill in the details and start shaping your character. I find the idea of trying such a new, shorter format in an established series quite appealing.

Expectations are different, and Andrew’s certainly aren’t wrong, but it seems to me we still carry quite a bit of baggage when it comes to how narrative choices in games should work. The obligation that these choices must be fair. That they must be well-informed. That they must be meaningful. These are worthwhile concedes to basic player agency and respect sometimes, perhaps even most of the time, but they can also be very restricting guidelines.

Expectations are different, and Andrew’s certainly aren’t wrong, but it seems to me we still carry quite a bit of baggage when it comes to how narrative choices in games should work. The obligation that these choices must be fair. That they must be well-informed. That they must be meaningful. These are worthwhile concedes to basic player agency and respect sometimes, perhaps even most of the time, but they can also be very restricting guidelines.

There’s a lot of interesting ground outside of these well-behaved choices, for decisions that are unfair, confusing, hard to reach, punishing once made, or simply meaningless. It may seem harsh to be asked to judge perfect strangers, but it’s something we all do on a daily basis. It may not be a lot of fun to make poor decisions, to be presented with dilemmas or Hobson’s choices, but we all know what it’s like to struggle with those, because few choices in life follow the neat and tidy rules we impose on those in games.

The selective rendering of decision-making and general dialogue in games like, say, Mass Effect does of course have its benefits. Heaps of information and the ability to pause unrealistically in the middle of conversation to ponder your options for a few minutes alleviate some of the stress associated with the kind of tough choices you are asked to make in the game, as does the ability to rewind via autosaves. It’s a convenient system for relaxed consideration, but making it worse, muddying up the process, can sometimes be far more interesting.

Alpha Protocol was a pretty substantially flawed RPG that offered skill sets of inconsistent and sometimes ludicrous usefulness and a mostly unsurprising plot about double-crossing spies and evil military contractors, but one of the things that definitely stuck in mind for me was the way it forced you to respond quickly in conversation, only giving you a very limited idea of how your counterpart and the current discussion fit into the big picture of its conspiracy (and, regrettably, often giving you an equally limited idea of how your character might interpret a certain dialogue prompt). The system did not always work as well as it could, but turning dialogue into an arena rather than a leisurely exchange of lines benefited the idea of a nebulous spy story. Of more recent note, I could once more bring up Spec Ops: The Line and it’s core choice of “Be an asshole or stop playing the game”, that some consider pretty stupid and I maintain is absolutely brilliant.

Alpha Protocol was a pretty substantially flawed RPG that offered skill sets of inconsistent and sometimes ludicrous usefulness and a mostly unsurprising plot about double-crossing spies and evil military contractors, but one of the things that definitely stuck in mind for me was the way it forced you to respond quickly in conversation, only giving you a very limited idea of how your counterpart and the current discussion fit into the big picture of its conspiracy (and, regrettably, often giving you an equally limited idea of how your character might interpret a certain dialogue prompt). The system did not always work as well as it could, but turning dialogue into an arena rather than a leisurely exchange of lines benefited the idea of a nebulous spy story. Of more recent note, I could once more bring up Spec Ops: The Line and it’s core choice of “Be an asshole or stop playing the game”, that some consider pretty stupid and I maintain is absolutely brilliant.

Between The Walking Dead, The Yawgh, Save The Date, Kentucky Route Zero and an ever increasing number of brilliant Twine games, we could be experiencing something akin to a multiple choice renaissance just now, a prospect I find exciting because of the novel ways people have been using the system. The words “multiple choice dialogue” used to be pretty misleading, the choices offered in conversation were rarely narrative so much as purely systemic – which of several interchangeable responses to pick, which question to ask first (even though all would be asked eventually), which of the freely accessible conversation nodes to move to (“Tell me more about X!” until, eventually “I think I heard enough about X”). Even when a yes-or-no choice reared its head, failing to pick the option your partner wanted to hear just sent you back to the beginning of that dialogue tree more often than not.

To me, the appeal of The Walking Dead was that it replaced these stiffly frozen exposition slapfights with a more naturalistic approach to conversation, in which characters talked while doing other things instead of staring into each other’s eyes all the time, in which, again, you were forced to think and respond quickly, and in which your words felt meaningful, because they tended to be final.

On the other end of that spectrum are games that expose the limitations of multiple choice dialogue by explicitly turning it into a non-choice. One of the most interesting Twine games I’ve played recently was I Cheated On You, memorable because it turns the link, usually the domain of choice and agency in such games, the place where you pick how the story should continue, into mere set dressing, a huge, glowing testament to what you should have said. You wind up clicking it helplessly while the actual conversation runs on without your control.

In the case of 400 Days, the sparsity of background information, frustrating as it can be, turns dialogue into a world-building tool that allows you to fill in details yourself, to shape relationships and characters according to your interpretation. I would not discount the technique, even if the main game might have you expecting a more traditionally authored narrative. Of course, 400 Days might be a poor example: Its dramaturgy is far from perfect, the game frequently provides you with confusing or overwrought, hamfisted cues.

In the case of 400 Days, the sparsity of background information, frustrating as it can be, turns dialogue into a world-building tool that allows you to fill in details yourself, to shape relationships and characters according to your interpretation. I would not discount the technique, even if the main game might have you expecting a more traditionally authored narrative. Of course, 400 Days might be a poor example: Its dramaturgy is far from perfect, the game frequently provides you with confusing or overwrought, hamfisted cues.

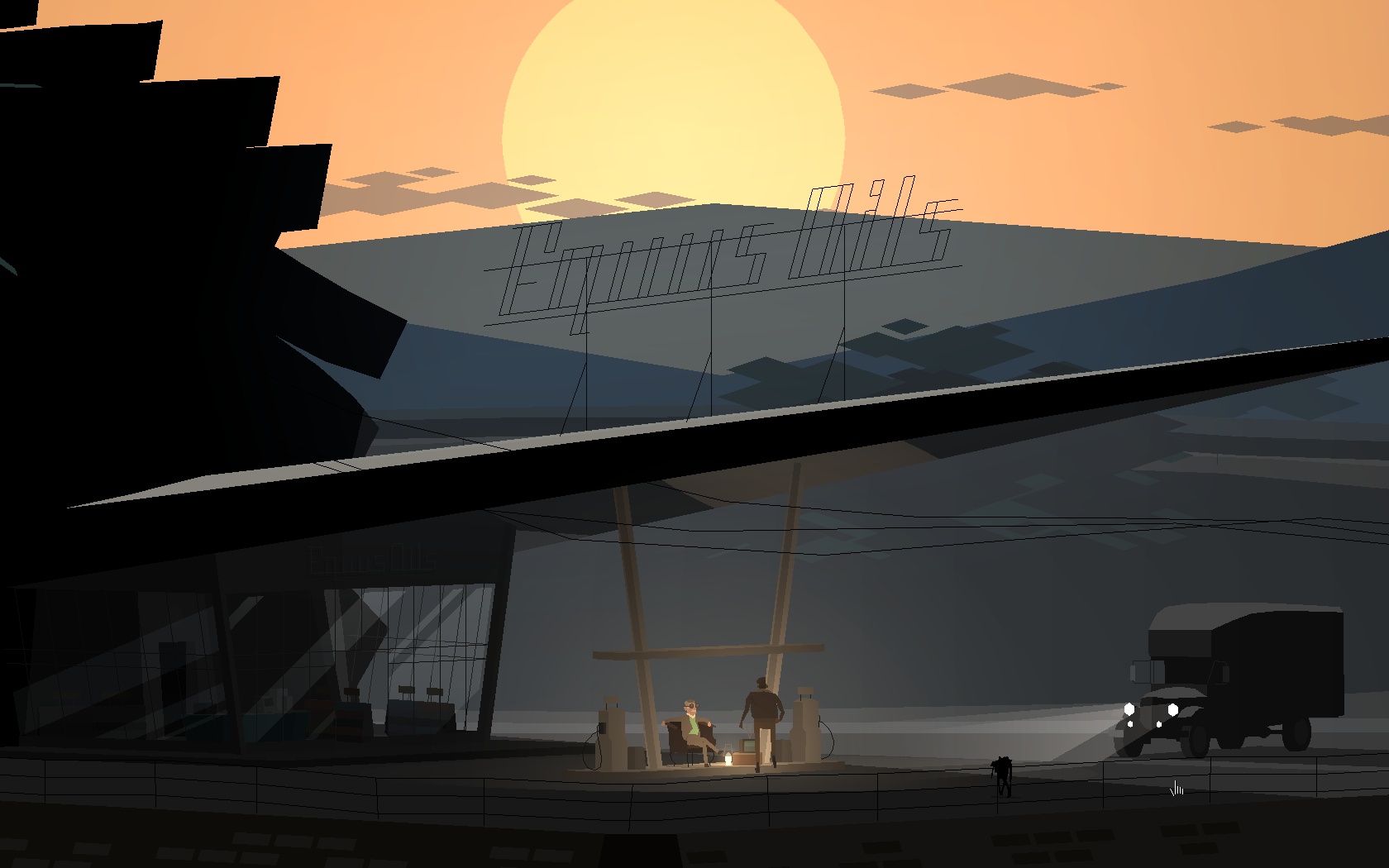

For a better look at the formative power of words, consider the fantastic Kentucky Route Zero. Though the specific stops of the trip through its weird Americana are set in stone, the game often lets you choose between multiple options in dialogue, monologue and even the reading of documents, to decide for yourself the finer details of its narrative. Is that dog yours? Is that name you keep mentioning a former employer or wronged friend?

It’s a technique that should be experienced first-hand, not just for fear of spoilers. The reason it works is because Cardboard Computer understand the difference a few carefully chosen words can make, and to my unending astonishment they have created a story you can influence both in broad strokes and minute detail, without ever clashing with the current events of its delivery run narrative.

Kentucky Route Zero returns their full creative power to words, they become a tool not just for announcing future intent, but willing into existence the particulars of your backstory, moving events by casually noting them and establishing your views by expressing them. Beyond describing reality, language has the power to create reality, through declarations (“I now pronounce you husband and wife” is the classic example), and its surrogate, in fiction.

Depending on your surroundings, the sentence “There’s a tree on the hill” could be accurate or inaccurate, but in fiction that sentence alone summons the tree, as well as the hill, before your mind’s eye. Worries of a withering imagination aside, games can realize and alter that vision in ways traditional storytelling can only dream of. We tend to achieve such efforts of expression through the manipulation of blocks – Minecraft comes to mind – but what if the same and a hundred other changes could be achieved by entering into a dialogue with the game itself?

Depending on your surroundings, the sentence “There’s a tree on the hill” could be accurate or inaccurate, but in fiction that sentence alone summons the tree, as well as the hill, before your mind’s eye. Worries of a withering imagination aside, games can realize and alter that vision in ways traditional storytelling can only dream of. We tend to achieve such efforts of expression through the manipulation of blocks – Minecraft comes to mind – but what if the same and a hundred other changes could be achieved by entering into a dialogue with the game itself?

Perhaps such a system would never be feasible on a comprehensive level: Presumably the same need for abstraction that forces Minecraft to use pixelated blocks requires Scribblenauts to entirely forego verbs in its lexicon. But to me, titles like Thirty Flights of Loving and Kentucky Route Zero show how curiously satisfying it can be to connect a few dots and fill in a few blanks, working with the game to create a narrative instead of consuming a strictly authored tale. Words have to power to create worlds – sometimes the prospect of using them as a painter’s brush seems more exciting than just picking the right thing to say.