Games of 2014 (12/15)

Combine The Wolf Among Us, The Walking Dead: Season 2, Electric Tortoise, The Fall and Broken Age to create today’s post.

The Wolf Among Us

With The Wolf Among Us Telltale did something unexpected. So unexpected that it took Telltale themselves half the season to realize where they’re going with it. What started out as a stereotypical noir crime story, as a whodunnit murder mystery, turned out to be a game about stories.

Everybody knows the stories about the big bad wolf and everybody knows he’s evil – characters in the game world as well as the players in front of the screen, remembering all those bloody fairy tales. Bigby wants to change, but he’s at the mercy of the person who holds the controller and pushes the buttons – and that person, the player, wants violence. Though The Wolf Among Us never actively breaks the fourth wall, every piece of the narrative is constructed around the players and their expectations, their prejudices and their demands.

While The Walking Dead has been an emotional journey, The Wolf Among Us is a reflection on the possibilities and limits of videogames as a narrative medium. It’s a treasure chest full of thoughts and ideas on storytelling and interaction design in videogames. But it’s also a story about prejudices, violence, about choice, change and consequences. It’s a narrative that only works because it’s told in a videogame and because it is played by a person.

Oh, and if you don’t care about those topics it’s also a really entertaining murder mystery story. But then you might as well watch a Let’s Play.

Daniel Ziegener writes about videogames on the German sites herzteile and Superlevel. He also tweets a lot.

The Walking Dead: Season 2

The Walking Dead: Season 2

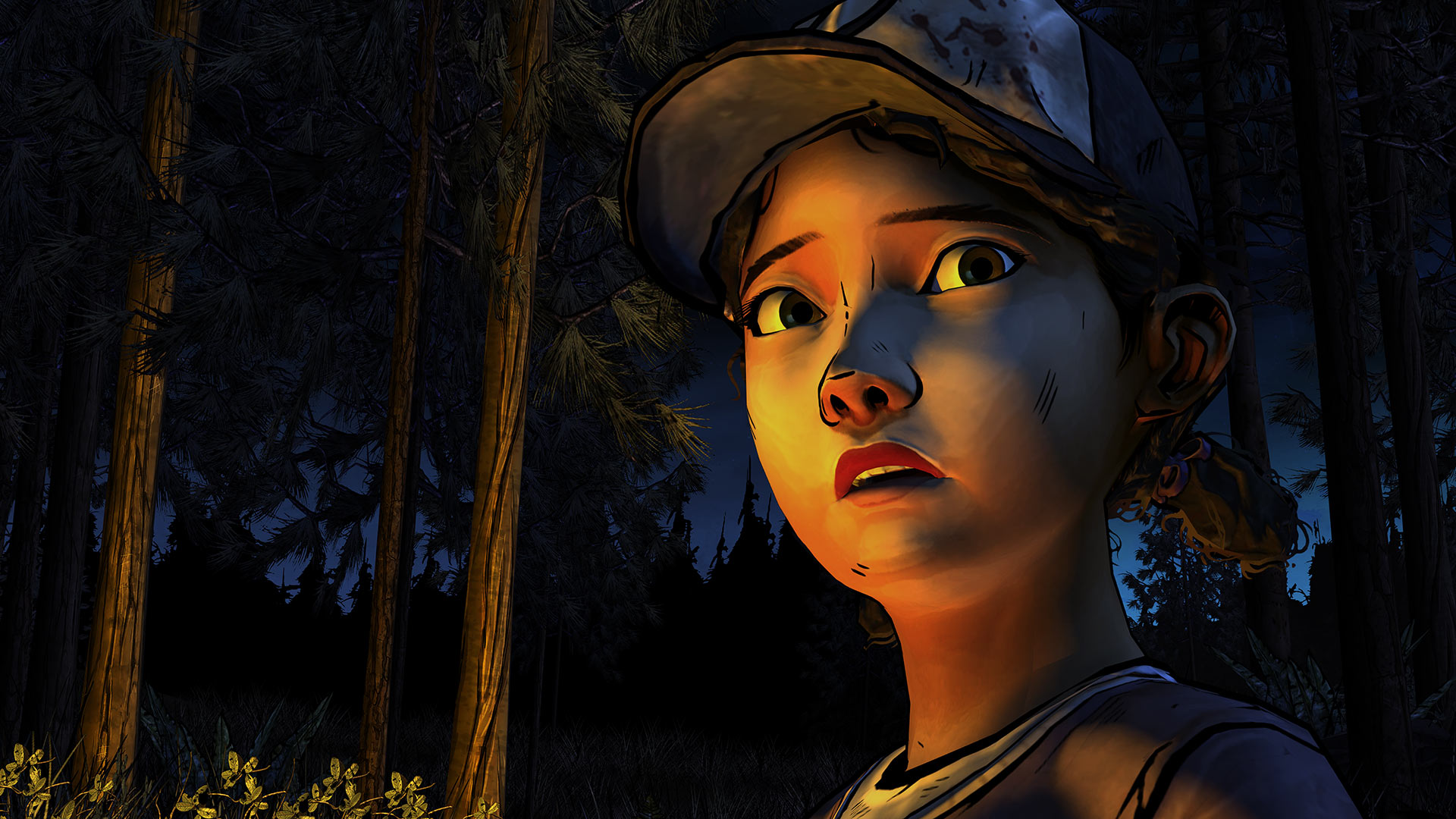

It’s tough to talk about the sequel to Telltale’s The Walking Dead without sobbing uncontrollably about the fate of Clementine. It’s even more difficult to discuss the second season of “A 10-year-old sweetheart trying to survive in the apocalypse” when everything the developers throw at her is a way of showing off how awful her life is. The adults tasked with looking after her can barely take care of themselves, walkers are roaming the countryside, ready to pounce at the first whiff of her scent, and she has to make life or death decisions when all she wants to do is go back to normal life.

The Walking Dead Season 2 is all about highlighting how awful Clementine has it, creating scenarios that rival those in the first season in terms of misery, and show off just how well-adjusted she is. She’s smart, resourceful, stealthy, and in reasonably good health. She knows how to keep calm when the odds are stacked against her, and she knows that in order to survive, people need to stick together. However, what she learns in Season 2 is how unreliable everyone is and how the only way to succeed in this kind of environment is to create a path for yourself.

It’s problematic to see all adults taking advice from a preteen, tripping all over themselves and their failures, but you do get to see a character, who has had nothing but the worst thrown at her, learn to stay resilient and lash out against those who are trying to take her down. That’s oddly encouraging and inspirational for a game about death. Plus, the “still not bitten” line is still one of the most powerful in games history.

Carli Velocci is a freelance journalist from Boston. You can see her work in Killscreen, Paste Magazine, and anywhere else brave enough to publish her. You can follow her on Twitter or at her website.

Electric Tortoise

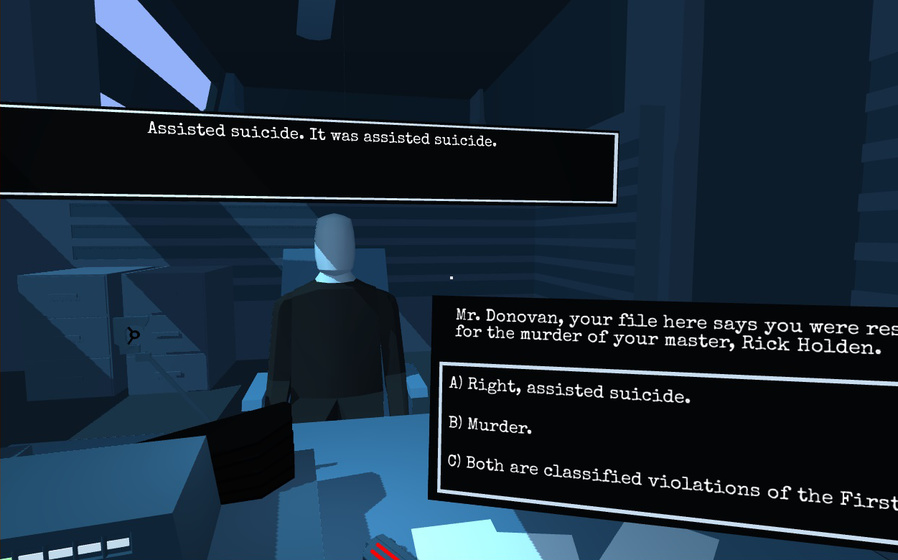

Electric Tortoise is inspired by Blade Runner, which alone tends to be enough to pique people’s interest. I’ve not seen Blade Runner so this tidbit meant little to me – instead, my interest was captured by its description as an “interrogation game.” And true enough, Electric Tortoise depicts a conversation between you and an android which invariably indicts you as a big smelly hypocrite.

This is a game interested in dignity and respect for life. How you choose to address the android, John Donovan, during your investigation of his murdered ‘owner’ reflects presumptions of a social and ontological hierarchy. I particularly love how the interface—you choose your dialogue options from an on-screen monitor – highlights conceits of spiritual grandeur of humanity with echoes of classical mind/body dualism. You can choose to snub Mr. Donovan’s existence but your only available manner of expression is dependent on artificiality; you sit at a man-made desk in a man-made room issuing man-made justice with your man-made authority according to man-made laws.

However you decide to treat him, the interrogation closes by mirroring the terms of assisted suicide which first incriminated the android. The reversal of positions inevitably humanizes Donovan by imbuing him with the status of his former anguished owner. You, then, are put in Donovan’s shoes as either bystander or assistant to his death, completing your role as mechanized agent in a satisfying twist of fate.

Stephen Beirne was born in August of 1986 and some time later began writing game criticism. You can find his work on Normally Rascal and support him on Patreon.

The Fall

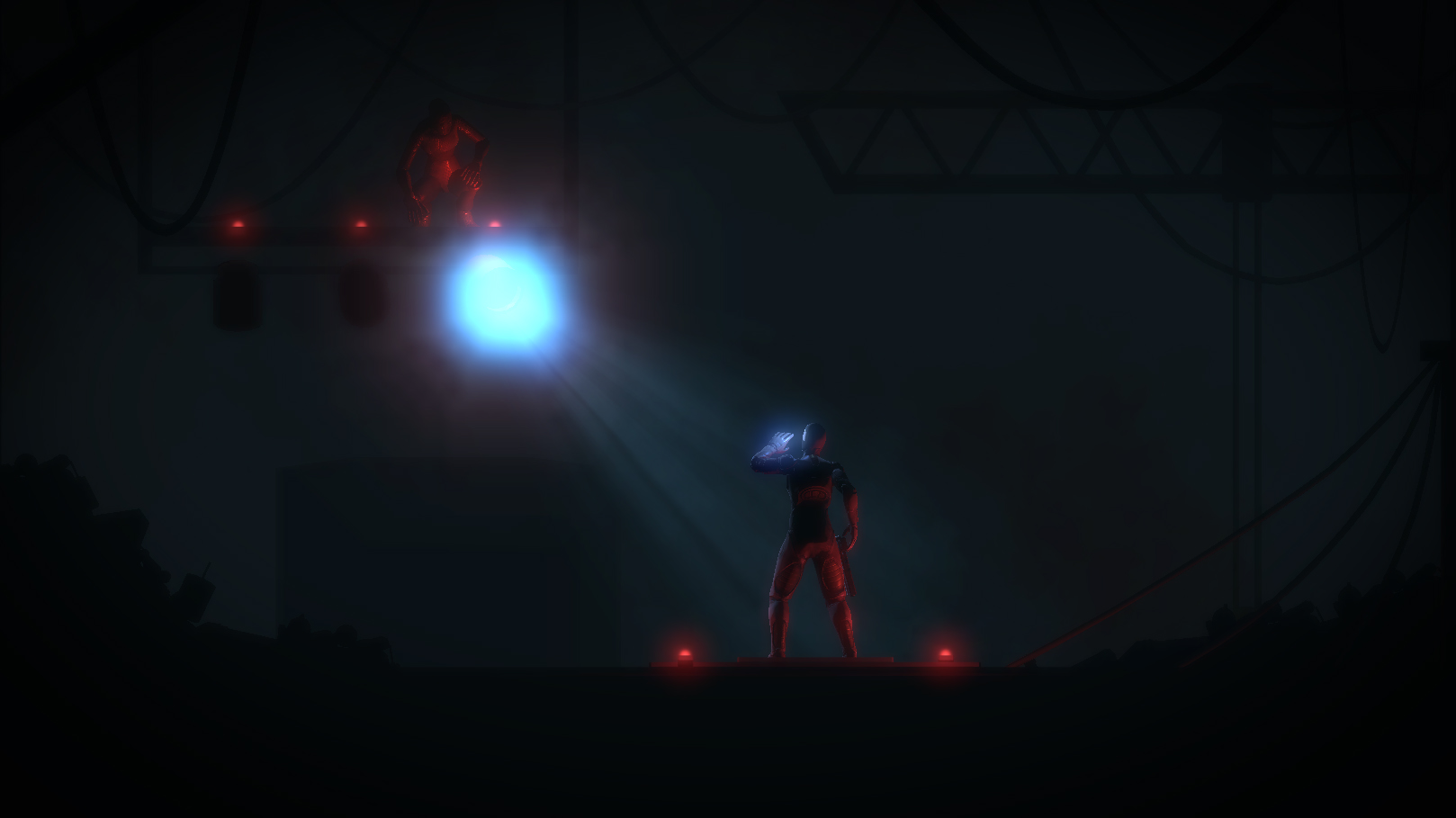

With the glut of dark, philosophical platformers clogging up the independent gaming space, one would be forgiven for scrolling past a game called The Fall. However, as formulaic as it might seem, The Fall’s generic name belies a mature and thought-provoking narrative about the nature of artificial intelligence that dovetails nicely with its delicate blend of light action and puzzle-solving. As an AI-controlled suit tasked with protecting its unconscious human pilot, the player must skirt around the hard limits of their characters’ own programming in order to progress through one of the most completely-realized game worlds we’ve seen in a long time.

Though the puzzles can occasionally fall into the realm of pixel-hunting, the cast of characters manage to engage with the underlying themes of the story without devolving to the heavy-handed philosophizing so common in games of its type. As with all episodic games, the cliffhanger is inevitable – however, here it feels natural and earned in a way that only the better works of Telltale have managed to pull off so far. All in all, it’s a strong start from developer Over the Moon Games. Let’s hope that episode two can keep the momentum going.

Steven T. Wright is a freelance writer living in and around the Southeastern United States. He enjoys text-heavy videogames, freshly-ground coffee, and hip-hop music from before he was born. You can find him on Twitter or his website.

Broken Age

In the wake of 2014, I don’t think it’s possible to talk about Broken Age without talking about Gamergate. As a Kickstarter-backed game from Tim Schaefer and Double Fine, Broken Age and its makers found themselves linked inconsolably to an frenzy of online fury linked to the realities of its production and the content and themes of its story, which would become appropriate given where the game goes.

Broken Age could best be described as one of gaming’s future classic fairy tales. Its textual language and tone resembles both the Lucasarts comedy adventures and edutainment games of the ’90s, a mode of play capable both of irreverent humor and successful education. In short, it is textually designed to imprint an idea on the player, and it’s almost delirious to see a mid-budget indie release so confidently wrap that idea in a feminist box.

It would be low-hanging fruit to label Broken Age as feminist on the grounds of its heroine Vella, but Broken Age’s grasp of feminism extends beyond the surface level and into the text. Vella and Shay’s stories weave both through the violence patriarchal forces sacrifice young women to and the false notions of heroism that men who perpetrate that violence are raised under. Both stories tell warnings about the way our society damages people on the basis of their gender, and both themes echoed back to us when Gamergate spread its ugly, mottled wings.

The constant danger of Gamergate has been that the game industry en masse would silently allow a handful of women to be sacrificed to a pack of monsters who used violence first and discussion last to achieve their objectives. If one looks at gaming’s greater history, this strange sacrifice is ritual, much like the way Broken Age’s people gleefully sacrifice to Mog Chothra.

And to Gamergate itself, how can its language of raids and operations and “standing up for beliefs” be read as anything other than a false stab at heroism? Gamergate’s members are not all white, nor all men, but one need not look further than the writings of “Based Mom” Christine Sommers to see how their ideology seeks to soothe and prop up the egos of confused young white men. No different then both Shay’s own companions propping up his ego and using his false heroism for their own goals.

With Act 1’s final twist showing that Shay’s ship was secretly Mog Chothra, the intersection between Broken Age’s world and ours is realized. Men lunging out and claiming the lives of women in the name of a false heroism, one woman bravely digging her heels in the sand and stringing together a series of unlikely events and tools to take it all down. Long ago I had wondered if this was a fairy tale Schaefer had hoped to use to educate his own daughter about the world, but now I find its warning far closer to our gaming world then I’d previously thought.

Bryant Francis is a games writer based out of Los Angeles who’s written for Gamasutra and The Jace Hall Show. See more of his work at website or find him on Twitter.